Getting Students Active through Safe Routes to School

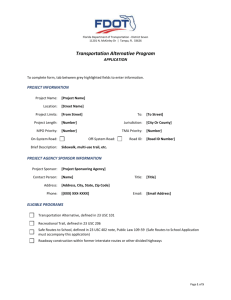

advertisement