This article was downloaded by: [Princeton University] Publisher: Routledge

advertisement

![This article was downloaded by: [Princeton University] Publisher: Routledge](http://s2.studylib.net/store/data/011979232_1-39d0143abb90f7b3499d7abd3f253d2a-768x994.png)

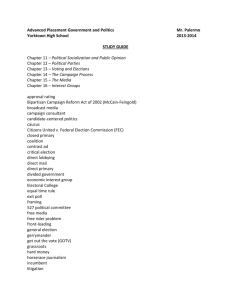

This article was downloaded by: [Princeton University] On: 03 January 2012, At: 08:34 Publisher: Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK Journal of Political Marketing Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/wplm20 Filled Coffers: Campaign Contributions and Contributors in the 2008 Elections a Keena Lipsitz & Costas Panagopoulos b a Queens College, CUNY, Flushing, New York, USA b Fordham University, Bronx, New York, USA Available online: 23 Feb 2011 To cite this article: Keena Lipsitz & Costas Panagopoulos (2011): Filled Coffers: Campaign Contributions and Contributors in the 2008 Elections, Journal of Political Marketing, 10:1-2, 43-57 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/15377857.2011.540193 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.tandfonline.com/page/terms-and-conditions This article may be used for research, teaching, and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, redistribution, reselling, loan, sub-licensing, systematic supply, or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae, and drug doses should be independently verified with primary sources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand, or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material. Journal of Political Marketing, 10:43–57, 2011 Copyright # Taylor & Francis Group, LLC ISSN: 1537-7857 print=1537-7865 online DOI: 10.1080/15377857.2011.540193 Filled Coffers: Campaign Contributions and Contributors in the 2008 Elections KEENA LIPSITZ Queens College, CUNY, Flushing, New York, USA Downloaded by [Princeton University] at 08:34 03 January 2012 COSTAS PANAGOPOULOS Fordham University, Bronx, New York, USA The presidential candidates alone in 2008 raised a stunning $1.75 billion, which was double the $881 million raised by candidates during the 2004 election cycle and more than triple the $529 million raised by candidates in 2000. Virtually all of this money was raised from individual contributions. In this article, the authors use survey data to examine the individual characteristics and political attitudes of contributors in 2008. KEYWORDS campaign finance, campaign fundraising, campaign spending, political contributions, 2008 presidential election Although the 2008 presidential election will be remembered chiefly because it was the first in which an African American was elected to that office, it is historic for another important reason: it was the first in which a major party candidate refused public financing for the general election campaign since the program was created in 1974. When Barack Obama announced his decision to forego public funding on YouTube on June 19, 2008, he declared that doing so was necessary because ‘‘Washington lobbyists’’ and ‘‘special interests’’ were ‘‘gaming’’ the system by giving money to 527 committees that were airing advertisements in support of his opponent, John McCain. Obama claimed that by foregoing public funding his campaign would be ‘‘truly funded by the American people’’ through small individual donations. Americans responded in large numbers, contributing heavily to both presidential campaigns as well as to the parties, other candidates for political office, Address correspondence to Keena Lipsitz, Assistant Professor of Political Science, Queens College, CUNY, 65-30 Kissena Boulevard, PH 200, Flushing, NY 11367, USA. E-mail: klipsitz@qc.cuny.edu 43 44 K. Lipsitz and C. Panagopoulos and groups. As we describe below, overall levels of campaign contributions soared over previous cycles in 2008. This article assesses the demographic characteristics and political attitudes and behavior of contributors in 2008. It also assesses whether the people who contributed to candidates and parties during the 2008 election season were any more representative of the general population than they were in 2004. Downloaded by [Princeton University] at 08:34 03 January 2012 POLITICAL CONTRIBUTIONS TO THE CANDIDATES IN 2008 The presidential candidates in 2008 raised a stunning $1.75 billion, which was double the $881 million raised by candidates during the 2004 election cycle, and more than triple the $529 million raised by candidates in 2000.1 Since political action committees rarely contribute to presidential candidates, virtually all of this money was raised through individual contributions. In 2008, candidates received the vast bulk of their individual contributions directly. Obama and McCain, however, also raised a portion of their funding from individuals through joint fundraising committees they formed with national party committees. The growth in financial contributions can be attributed to a number of factors. The first has to do with the decision of many candidates to forego the use of public funding, which allowed them to raise and spend significantly more money than if they had accepted public funds. The campaign finance system created in 1974 has two components. During the primary campaign, each individual contribution that a candidate receives is matched up to $250 by the federal government in exchange for the candidate abiding by statewide spending limits as well as to an overall aggregate spending cap. In 2008, that cap was approximately $50 million. In 2000, George W. Bush was the first presidential candidate to decline the primary matching funds. John Kerry and Howard Dean did the same in 2004. In 2008, virtually every serious contender for a party’s nomination opted out of the matching fund program. This allowed many of them, including Mitt Romney, Rudy Giuliani, John McCain, Barack Obama, and Hillary Clinton, to raise and spend significantly more than the $50 million matching fund limit during the primary. The other component of the presidential campaign finance system is the flat grant that party nominees receive for the general election, which amounted to $84.1 million in 2008. In exchange for the grant, a candidate must agree to spend only that money (plus legal and accounting costs). Obama’s decision to forego the general election grant allowed him to continue raising money during the general election campaign. The $337 million that Obama raised for the general election accounted for a fifth of all the funds raised by presidential candidates in 2008 (see Table 1). Yet, even if one subtracts this amount from the 2008 total, it was still a banner year for presidential contenders. 45 Campaign Contributions and Contributors in the 2008 Elections TABLE 1 Individual Contributions to Presidential Candidates in 2004 and 2008 Downloaded by [Princeton University] at 08:34 03 January 2012 Individual Itemized Contributions $200 or less $201–$999 $1000 or more # Total $ $ % $ % $ % 2008 PRIMARY Obama Clinton Edwards Richardson Dodd Biden Kucinich Gravel Dem subtotal McCain Romney Giuliani Paul Thompson, F. Huckabee Tancredo Brownback Hunter Thompson, T. Gilmore Rep subtotal Total primary 404,843 170,747 33,017 18,211 7,911 7,148 3,542 593 646,012 168,194 44,700 39,250 32,426 17,017 13,744 3,419 2,980 1,660 752 239 324,381 970,393 409.2 194.0 38.6 21.8 11.8 9.6 4.4 0.5 735.5 203.5 59.8 55.0 34.3 23.2 16.0 4.0 3.5 2.3 1.0 0.4 403.0 1138.5 121.2 43.0 11.8 3.5 1.0 1.6 2.5 0.3 184.4 42.2 4.7 3.5 13.4 8.9 4.6 2.2 1.2 1.1 0.1 .03 81.9 266.3 30 22 31 16 9 17 56 52 25 21 8 6 39 39 29 55 34 45 8 9 20 23 113.1 43.8 8.5 4.0 0.9 1.3 1.1 0.01 178.1 40.1 7.9 5.6 9.6 4.2 3.8 1.1 0.1 0.04 0.01 0.03 73.8 251.8 28 23 22 18 8 13 26 24 24 20 13 10 28 18 23 28 22 19 15 9 18 22 174.4 107.7 18.3 14.3 9.8 6.7 0.1 0.01 373.0 121.2 47.2 45.9 11.3 10.1 7.7 0.1 1.5 0.1 0.1 0.03 247.4 620.3 43 56 47 65 83 70 19 24 51 60 79 83 33 43 48 18 43 36 77 83 61 54 2008 GENERAL Obama 287,143 336.9 114.1 34 79.2 23 143.1 42 2008 COMBINED PRIMARY AND GENERAL Obama 691,986 746.1 181.3 24 207.9 28 356.8 48 2004 PRIMARY Kerry Dean Edwards Clark Lieberman Gephart Kucinich Graham Sharpton Moseley-Braun Dem subtotal Bush Total primary 20 39 7 19 5 10 44 7 4 16 21 26 23 51.5 16.4 3.2 4.3 2.6 2.1 3.0 0.8 0.2 0.1 84.2 37.7 121.9 24 32 15 25 18 15 38 18 38 28 24 15 20 120.8 14.6 16.9 9.7 10.8 10.7 1.5 3.3 0.3 0.3 188.9 153.3 342.2 56 29 78 56 77 75 19 75 58 56 54 60 57 206,030 54,448 18,113 17,770 13,345 12,243 9,483 4,098 2,617 588 338,735 190, 352 529,087 215.9 51.0 21.6 17.3 14.0 14.3 7.9 4.4 0.6 0.5 347.5 257.4 604.9 43.6 20.0 1.5 3.3 0.7 1.5 3.5 0.3 <0.1 0.1 74.4 66.4 140.8 Note. Sources: Federal Election Commission; Campaign Finance Institute. Several factors help to account for the significant jump in the amount of money raised during 2008. This was the first election since 1952 that did not feature an incumbent president or vice president as candidates. Spirited Downloaded by [Princeton University] at 08:34 03 January 2012 46 K. Lipsitz and C. Panagopoulos contests for the nomination in both parties boosted the level of interest in the election. Perhaps the best indicator of this was the fact that voter turnout returned to the levels of the 1950s and 1960s, when it was typical for it to be well above 60 percent. The 62 percent turnout rate for 2008 was two percentage points higher than in 2004 and 8 percentage points higher than in 2000 (McDonald 2009). A report by the Pew Research Center for the People and the Press found that interest in the campaign was significantly higher than in any presidential election since 1992.2 This enthusiasm, however, appeared to be concentrated chiefly among Democrats. In fact, the report described a significant ‘‘enthusiasm gap’’ between supporters of McCain and Obama. The higher level of engagement in the campaign, as well as the enthusiasm gap, was reflected—perhaps to an even more remarkable degree—in the number of individuals making donations of more than $200 to candidates.3 During the 2004 primary, 338,735 donors contributed to Democratic candidates, while 190,532 contributed to George W. Bush (see Table 1, Column 1). In 2008, the number of donors contributing to Democratic candidates swelled to 646,012, while just 324,381 donors contributed to Republicans. The surge in donations to Democrats was due not only to the fact that Obama had nearly double the amount of donors that John Kerry did in 2004 (404,843 vs. 206,030, respectively) but that Hillary Clinton moved an additional 170,747 individuals to make contributions of more than $200 to her campaign. In contrast, only 54,448 made such donations to Howard Dean in 2004. John McCain had fewer donors than George W. Bush in 2004, but other candidates, such as Romney and Giuliani, convinced a significant number of individuals to contribute. During the general election, 287,143 individuals gave more than $200 to Obama, but it is very likely that a significant portion of these people also gave during the primary, since Obama was especially adept at convincing donors to contribute more than once (Malbin 2009). The growth in small donors during the 2008 election was also dramatic. Although the Federal Election Commission (FEC) does not require the disclosure of individuals who give less than $200, the Campaign Finance Institute has calculated the aggregate amounts contributed by small (less than $200) donors to each candidate. During the 2004 primary, Bush raised $66.4 million from small donors, while Kerry raised $43.6 million and Dean raised $20 million in such contributions. Although McCain raised less from small donors than Bush during the 2008 primary ($42 million), Clinton raised as much in small donations as Kerry did in 2004, while Obama raised an impressive $121 million from small donors. During the general election campaign, Obama raised more funds from small donors than McCain’s entire general election allowance. Thus, there is no question that Obama did a better job of attracting small donors than any other presidential candidate in recent history. That said, the staggering amounts raised by Obama from small donors obscures the fact that, as a percentage of overall intake, these Downloaded by [Princeton University] at 08:34 03 January 2012 Campaign Contributions and Contributors in the 2008 Elections 47 sums were not significantly higher than those of other Democratic candidates in recent history or even George W. Bush in 2004 for that matter. During the primary, Obama raised 30 percent of his funds from small donors. Dean raised 39 percent of his primary funds from such contributions in 2004, while Edwards raised 31 percent of his funds in similarly small sums during the 2008 primary. In 2004, Bush also raised 26 percent of his funds from small contributors. Because Obama had to rely on large donors to help him get his primary campaign off the ground, he was actually able to increase the proportion of this funding that came from small donors in the general election to 34 percent. The real story of 2008 is that more individuals contributed to Obama at every level of giving. Obama received a historic number of small, medium, and large donations. As Michael Malbin (2009, 17) observes, ‘‘[Obama’s] ship was riding higher at all levels.’’ Prior to the 2008 primary, Bush held the records for funds raised from small and large (over $1000) donors ($66.4 million and $153.3 million, respectively), while John Kerry held the record for funds raised from contributions ranging from $201-$999 ($51.5 million). Obama shattered the small and large donations records not only in the primary but also in the general election. In terms of large donations, Obama bested Bush’s record by more than $20 million during the primary and then fell just short in the general. Obama’s fundraising prowess in the 2008 cycle is noteworthy. His campaign’s ability to woo small and medium-sized donations rested largely on its savvy use of the Internet. In 2000, John McCain was the first candidate to illustrate how quickly a candidate could raise money over the Internet by raising $1 million overnight after the New Hampshire primary. In 2004, Howard Dean built upon the McCain model, adding a social networking dimension to it by using the Web site Meetup to organize volunteers. Obama, however, took both the fundraising and social networking aspects of Internet fundraising to a whole new level with My.BarackObama.com. In essence, he fused the two. Whereas Dean and McCain had used a simple interface to allow a person to click on an amount and donate, the Obama Web site combined this with social networking. My.BarackObama.com allowed people to create their own page on the site and set a personal fundraising target. A person could then use another application to e-mail friends and encourage them to donate (Green 2008). When they did, a ‘‘thermometer’’ on the person’s page indicated how close she was to achieving her target. In this way, the Web site allowed anyone with the inclination and enthusiasm to become a ‘‘mini’’ bundler of sorts. These technology innovations helped the Obama campaign to shatter small donor fundraising records in presidential campaigns. In addition to the ability to donate using a subscription model, people who signed up for e-mail updates from My.BarackObama.com were encouraged to give more than once. Frequently, people who gave multiple times Downloaded by [Princeton University] at 08:34 03 January 2012 48 K. Lipsitz and C. Panagopoulos surpassed a total of $200 but stayed below the $1000 mark, allowing Obama to set records for medium-sized contributions as well. In fact, Obama’s ability to attract repeat donors has been described as one of the ‘‘sweet spots’’ of his fundraising campaign (Malbin 2009, 17). Obama’s attentiveness to small and medium-sized donors was matched by an equal attentiveness to those who were willing to give in spades. Nearly half of the $357 million that Obama raised in large donations during the primary and general elections were raised by bundlers. These individuals solicit money from others. Bush was the first presidential candidate to create a system for identifying and rewarding bundlers. In the 2000 campaign, individuals who solicited more than $100,000 for the campaign were called ‘‘pioneers.’’ Bush added the ‘‘ranger’’ category in 2004 for those who collected more than $200,000, as well as ‘‘maverick’’ for individuals younger than 45 who promised to raise $50,000 for the campaign. Kerry adopted Bush’s strategy in 2004 with his ‘‘vice-chairs’’ and ‘‘co-chairs.’’ Both Obama and McCain continued this tradition in 2008. It is difficult to pin down the exact amount raised by bundlers for each campaign because bundler fundraising levels are typically categorized by range, but the Center for Responsive Politics estimates that 560 individuals were responsible for soliciting at least $75 million for Obama, while 536 people solicited at least the same amount for McCain. In reality, the total amount of money raised by bundlers for each campaign was probably much higher because these estimates are determined using the low end of the ranges reported by the campaigns. Still, these numbers suggest that a sizeable portion of the large donations raised by each nominee were channeled to the campaigns by a small number of elite individuals. Another development in the 2008 election, which was also part of the large donor story, was the role of joint fundraising committees. Candidates could solicit money for these committees and individuals could write checks for as much as $70,000 to them. These contributions were then distributed to the candidates, the national party committee, and various state party committees. These committees were not new; together Gore and Bush raised $5.2 million for their joint fundraising committees in 2000, while Kerry and Bush raised a combined total of $51.4 for theirs in 2004. What was new about 2008 was that joint fundraising committees became a central component of both the candidates’ and parties’ fundraising strategies. According to the Center for Responsive Politics, Obama raised $288 million through his joint committees while McCain raised $221 million. Of the $288 million raised by Obama through these committees, $87 million was distributed to his campaign, $103 million went to the Democratic National Committee (DNC), and the remainder was distributed to Democratic state parties. McCain received $22 million from his joint committees, while the Republican National Committee (RNC) pocketed $120 million and the remainder was spread out among Republican state parties.4 49 Campaign Contributions and Contributors in the 2008 Elections Downloaded by [Princeton University] at 08:34 03 January 2012 Because of the prominent role these committees played in the 2008 election and the fact that candidates can solicit funds for them, campaign finance reformers claim the joint committees are a new ‘‘loophole’’ that has effectively raised individual contribution limits and allowed a small group of ‘‘mega-donors’’ to donate well in excess of the $4,600 ($2,300 in the primary and $2,300 in the general elections) individual contribution limit. An analysis of FEC records by Public Citizen revealed that more than 2,205 individuals contributed in excess of $25,000 through Obama’s joint fundraising committees. McCain had 1,846 mega-donors.5 Below we examine more closely the extent to which the donor pool may have been expanded in 2008, as well as how representative donors were compared to the larger electorate. POLITICAL CONTRIBUTIONS TO THE PARTIES IN 2008 For the most part, the national party committees encountered greater difficulty raising money in 2008 than did the candidate committees. The exceptions were the Democratic Hill committees, which benefited from the enthusiasm generated by the possibility of tipping Congress further in their favor. As Table 2 reveals, the Democratic Senatorial Campaign Committee (DSCC) raised nearly double what it did in 2004, while the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee (DCCC) increased its take by more than 50 percent. The DNC raised considerably less than it did in 2004, however, and found itself trailing far behind the RNC throughout the primary and general election seasons. Their troubles started early, with the DNC finishing up 2007 with $50.5 million in its coffers compared to the RNC’s $83 million. The DNC fell further behind during the primary season as Clinton and Obama TABLE 2 Contributions to National Party Committees in 2000, 2004, and 2008 2000 Party committee Hard Soft Total 2004 Hard=Total 2008 Hard=Total DNC DSCC DCCC Total democratic RNC NRSC NRCC Total republican Overall 124.0 40.5 48.4 212.9 212.8 51.5 97.3 361.6 136.6 63.7 56.7 257.0 166.2 44.7 47.3 258.2 260.6 104.2 105.1 469.9 379.0 96.1 144.6 619.7 1,089.6 311.5 88.7 93.0 493.2 392.4 79.0 185.7 657.1 1,150.3 260.1 162.8 176.2 599.1 427.6 94.4 118.3 640.3 1,239.4 Note. Source: Federal Election Commission; Center for Responsive Politics. DNC ¼ Democratic National Committee; DSCC ¼ Democratic Senatorial Campaign Committee; DCCC ¼ Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee; RNC ¼ Republican National Committee; NRSC ¼ National Republican Senatorial Committee; NRCC ¼ National Republican Congressional Committee. Downloaded by [Princeton University] at 08:34 03 January 2012 50 K. Lipsitz and C. Panagopoulos siphoned off more potential donors during the protracted Democratic primary. The DNC was also competing for donors with the DSCC and the DCCC. By the end of April 2008, the RNC had raised an additional $58 million, while the DNC had raised less than half that amount. The DNC began to have more success during the summer months as Obama began to appear at joint committee fundraisers. By the end of the general election campaign, the DNC had raised $260.1 million, with approximately $100 million of that coming from joint fundraising committees.6 In contrast, the RNC had a solid fundraising year, bringing in $427.6 million by the end of the general election season with $120 million coming from joint committees. The Republican Hill Committees had a harder time attracting funds, with the National Republican Senatorial Committee attracting considerably less than its Democratic counterpart ($94 million) and the National Republican Congressional Committee raising less than it did in both 2000 and 2004 ($118 million vs. $145 million and $186 million, respectively). CONTRIBUTORS IN THE 2008 PRESIDENTIAL ELECTION CYCLE We proceed to use survey data to analyze contributing behavior and donor traits in 2008. Studies of contributors in U.S. elections typically conclude that donors are wealthier, better educated, older, and more often white than noncontributors (Francia et al., 2003). A key question is whether the population of donors during the 2008 election was any more representative of the wider electorate than donors in previous years. To answer this question, we turn to the 2008 National Election Study (NES) administered by Stanford University and the University of Michigan. It asks respondents to indicate whether they contributed to a candidate,7 party, or group during the campaign. The following analyses use post-election weights supplied by the NES. This was especially important in 2008 because the survey oversampled Latino and African American respondents. Table 3 shows the percentage of respondents who reported contributing to candidates, parties, and other political groups in 2004 and 2008. As expected, there was a significant increase in the percentage of Americans who reported donating to a Democratic candidate in 2008. Whereas only 4 percent claimed to have made a contribution in 2004, 7 percent did so in 2008. There was a small increase in the percentage of respondents who indicated they donated to a Democratic Party committee (from 4 to 5 percent). Just 4 percent of respondents reported giving to a Republican candidate in 2008 compared to 5 percent 2004. These figures were identical for Republican Party committees. It appears that contributions to other organizations, such as 527 committees, decreased in 2008. Four percent of the respondents reported contributing to such organizations while 6 percent did in 2004. 51 Campaign Contributions and Contributors in the 2008 Elections TABLE 3 Percentage Contributing to Candidates, Parties, and Other Groups in 2004 and 2008 Democratic candidate Democratic party Republican candidate Republican party Other group Any contribution 2004 2008 4 4 5 5 6 16 7 5 4 4 4 15 Downloaded by [Princeton University] at 08:34 03 January 2012 Note. Source: National Election Study. Calculated using post-election survey weights. Overall, our results suggest the segment of the electorate that contributed to political causes in 2008 was comparable to 2004. In 2008, 15 percent of respondents reported contributing to political causes, compared to 16 percent in 2004. Taking population growth in the intervening years into account, these estimates imply that about 35 million Americans made campaign contributions in both cycles.8 Even if the claims we advance above about an expanded presidential donor pool are true, there is scant evidence of a sizable bump in the number (or share) of Americans who report contributing in 2008. We infer from these results that the presidential campaigns may have attracted more donors in 2008, but this growth may have come at the expense of contributing to candidates or groups at other levels. To determine whether those who gave in 2008 were any more representative of the general population than in 2004, we use logistic regression to regress reported donating on a range of demographic and political variables that have been shown to predict donating behavior. The demographic variables include income, education, age, race, and gender, while the political variables include party identification, strength of partisanship, and interest in the campaign.9 The models also control for the competitiveness of the respondent’s state, as well as whether the respondent indicated that she had been contacted by a candidate or party during the course of the campaign season. A study of contributors in the 2004 also found that people who identify as being ideologically moderate were significantly underrepresented among contributors (Panagopoulos and Bergan 2006). To assess whether this was the case in 2008, we used the NES 7-point ideology question. To create a measure of extremism, we recoded this scale so that a 0 indicates that an individual is moderate while a 3 indicates that the individual is very ideologically committed. We estimate models for both 2004 and 2008. The model estimates explaining donating in both election cycles are shown in Table 4. Models 1 and 2 examine the factors explaining donating irrespective of the candidate or cause to which the respondent donated. Models 3 and 4 examine the predictors of donating to Republican or Democratic causes in 2008. Together, the models show that the pool of donors has become generally less representative of the larger population, compared to 2004, but 52 K. Lipsitz and C. Panagopoulos Downloaded by [Princeton University] at 08:34 03 January 2012 TABLE 4 Logistic Regression Models Explaining Donating in 2004 and 2008 Income Education Age Male White State competitiveness Strong democrat Weak democrat Weak republican Strong republican Contacted Campaign interest Extremism Intercept N Log likelihood Pseudo R2 2008 2004 Any Contribution Any Contribution To Democrats To Republicans 0.21# (0.12) 0.33 (0.10) 0.04 (0.01) –0.14 (0.26) 0.44 (0.33) –0.22 (0.11) 1.16 (0.32) –0.38 (0.32) –0.12 (0.31) 0.30 (0.29) 0.65 (0.29) 0.66 (0.24) 0.43 (0.14) –8.19 (0.84) 775 –234.13 0.25 0.274 (0.10) 0.394 (0.07) 0.014 (0.001) 0.34# (0.18) 0.23 (0.22) 0.05 (0.11) 0.75 (0.27) –0.146 (0.30) –0.83 (0.34) 0.068 (0.27) 0.89 (0.21) 0.63 (0.24) 0.702 (0.14) –7.53 (0.67) 1,929 –647.01 0.21 0.19 (0.13) 0.33 (0.08) 0.01 (0.01) –0.01 (0.24) 0.22 (0.26) –0.03 (0.13) 1.12 (0.30) 0.09 (0.35) –2.87 (0.84) –3.12 (0.79) 0.94 (0.25) 0.57# (0.35) 0.54 (0.17) –6.61 (0.75) 1,927 –402.24 0.25 0.50 (0.22) 0.45 (0.12) 0.03 (0.01) 0.23 (0.32) –0.35 (0.49) –0.12 (0.20) –2.88 (1.09) –1.22# 0.75 0.88 (0.46) 1.54 0.45 1.12 (0.38) 0.75 (0.55) 0.67 (0.23) –11.15 (1.80) 1,927 –237.88 0.34 Note. Source: 2004 and 2008 National Election Studies. Dependent variable for models 1 and 2 is coded ‘‘1’’ for having contributed to a candidate, party, or group and ‘‘0’’ for not having contributed. In model 3, the dependent variable is coded ‘‘1’’ if the respondent contributed to a Democratic candidate or party committee and ‘‘0’’ otherwise. In model 4, the dependent variable is coded ‘‘1’’ for having contributed to a Republican candidate or party committee and a ‘‘0’’ otherwise. All models use logistic regression. Independents (including leaners) are the omitted category for partisanship. Post-election survey weights used ( p < .001; p < .01; p < .05; #p < .10, two-tailed). this appears to be driven by the fact that those who contributed to Republican candidates and parties have become more distinctive. Those giving to Democratic interests have actually become more representative for the most part. Models 1 and 2 show that age was a much weaker predictor of donating in 2008 than it was in 2004. For example, the predicted probability that a 30-year-old would donate in 2004 was 5 percent, while the likelihood of a 60-year-old giving was 13 percent. In 2008, those numbers were 6 and 9 percent, respectively, indicating that age mattered much less for donating. This is consistent with the anecdotal evidence that campaigns in 2008, and the Obama campaign in particular, successfully appealed to younger donors for financial support. When we turn to models 3 and 4, we see that age matters less mainly for those contributing to Democrats, while age remains a highly significant predictor of those giving to Republican causes. Income, education, and gender all seemed to matter more for donating in 2008 relative to 2004. Even though Obama drew more small donors into the contributor pool, model 2 indicates that these donors did not make the donor pool overall any more representative in terms of income. There are two possible explanations for this. The first is that the new donors in 2008 Downloaded by [Princeton University] at 08:34 03 January 2012 Campaign Contributions and Contributors in the 2008 Elections 53 were simply wealthy people who had never been compelled to give in the past. Something about the 2008 election suddenly made them decide to open their wallets. It is also possible that the small donors brought in by one party were balanced out by more wealthy donors brought in by the other. If this is case, income should matter more for giving to Republican causes than Democratic causes in 2008. Models 3 and 4 show that income is a significant predictor of contributing only to a Republican cause. The size and significance of the coefficient suggest that donors to Republican interests were even wealthier than they were in 2004. Although the income variable is positive for those who gave to Democrats, it is not statistically significant. Model 2 shows that education became a stronger predictor for donating than it was in 2004, but the larger size of the coefficient appears to be driven mainly by those giving to Republicans. The predicted probability of giving to any candidate or party in 2008 tripled between those who had a high school degree and those who had a bachelor’s degree (5 vs. 16 percent). Among those giving to Republican candidates and party committees, the predicted probability was 3.3 times higher for those with a bachelor’s degree compared to those having only a high school diploma (1 vs. 0.3 percent), while it was only 2.6 times higher for those giving to Democrats (2.5 vs. 6 percent). In terms of the gender and race, model 2 suggests that men were marginally more likely to give in 2008, while gender made no difference in 2004. Race appears to have made no statistically significant difference in either year, despite the fact that 2008 featured an African American Democratic candidate. Turning to the political variables, strong Democrats were significantly more likely to give in 2004 than independents, weak Democrats, weak Republicans, and strong Republicans.10 This was also the case in 2008, although the smaller size of the strong Democrat coefficient (0.75 vs. 1.16) suggests that it was a somewhat weaker predictor of giving in 2008. It also appears that weak Republicans were significantly less likely to give in 2008, compared to independents, weak Democrats, and strong Republicans. In terms of the other political variables, we see that the importance of being interested in the campaign for donating did not change between 2004 and 2008. The coefficients for both years are virtually identical. Being contacted by someone from a campaign, party, or group seemed to matter a bit more for donating in 2008 than 2004, however. Whereas the predicted probability of donating was 1.8 times higher for those who were contacted in 2004, it was 2.3 times higher in 2008.11 Interestingly, models 3 and 4 show that both interest and being contacted mattered slightly more for those donating to Republican causes than those giving to Democratic ones in 2008. Perhaps the most interesting difference emerging from the analysis is that the pool of donators in 2008 was even more ideologically extreme than it was in 2004. In fact, after education, ideological extremism was the most important predictor of giving in 2008. In 2004, the predicted probability of donating increased by 12 percentage points as respondent extremism Downloaded by [Princeton University] at 08:34 03 January 2012 54 K. Lipsitz and C. Panagopoulos increased from its minimum to its maximum. In 2008, the predicted probability increased by 19 percentage points over the same range. As was the case with campaign interest and being contacted, models 3 and 4 show that extremism mattered slightly more for those donating to Republican causes in 2008. Overall, the analysis shows that the pool of donators in 2008 was probably less representative of the general population than it was in 2004. Demographically speaking, it does appear that donors giving to Democratic causes in 2008 were more representative of the general population than those giving to Republican causes. Whereas the former are simply more educated than the general population, the latter are more educated, wealthier, and older, which is more in line with what previous studies have found of donors generally. In terms of political variables, donors in 2008 were more ideologically extreme than they were in 2004. In the next section, we take closer look at the role that ideology played in donor behavior in 2008. CONTRIBUTING AND IDEOLOGY IN THE 2008 PRESIDENTIAL CAMPAIGN How did contributors differ from noncontributors ideologically? First, contributors were significantly more liberal than noncontributors in 2008. Contributors averaged 3.98 and noncontributors averaged 4.33 on the 7-point ideology scale.12 A study of contributors in 2004 found that moderates were grossly underrepresented among donors while those with more extreme views were overrepresented (Panagopoulos and Bergan 2006). Figure 1 shows that the story was similar in 2008. Moderates continued to be underrepresented: 12 percent of survey respondents and just 6 percent of those who reported contributing were moderates. Those claiming to be ‘‘extremely liberal’’ were five times more likely to be found among contributors than noncontributors while those who were ‘‘extremely conservative’’ were twice as likely. Both liberals and conservatives were overrepresented among donors as well. The main difference between 2004 and 2008 was that people who reported being ‘‘slightly conservative’’ were just as likely to be underrepresented among the self-reported donors as moderates. This finding is especially perplexing given that such individuals should have found McCain’s moderate conservatism appealing. This finding may reflect these individuals’ disappointment with McCain’s need to cater to his base during the primary. Table 5 takes a closer look at how the political attitudes of donors to Republican and Democratic interests differed from those who did not donate in 2008. The issues listed first in the table are those on which contributors on both sides of the partisan divide held attitudes that were significantly different from noncontributors. The issues listed later are cases in which only 55 Downloaded by [Princeton University] at 08:34 03 January 2012 Campaign Contributions and Contributors in the 2008 Elections FIGURE 1 Ideology of noncontributors and contributors in 2008. those contributing to Democratic or Republican interests held significantly different views. The difference between contributors and noncontributors was not statistically significant in only one case: increasing spending on the environment. In all other cases, there were sizable differences. TABLE 5 Political Attitudes of Noncontributors and Contributors in 2008 Favor gay marriage Favor affirmative action Favor path to citizenship Favor reducing deficit by raising taxes Favor universal health coverage Favor no limitations on abortion Better if women stay home Increase spending: war on terror Increase spending: aid to poor Increase spending: environment Did not contribute Contributed to democratic candidate or party Contributed to republican candidate or party 17 21 48 19 53 48 30 50 52 53 67 35 74 53 69 48 10 56 56 57 7 3 25 8 4 12# 38 35 31 42 Note. Source: 2008 National Election Study. Entries are percentages of respondents in category agreeing with position. All percentages are calculated using pre-election survey weights ( p < .001; p < .01; p < .05; #p < .10, two-tailed). Downloaded by [Princeton University] at 08:34 03 January 2012 56 K. Lipsitz and C. Panagopoulos Contributors to both Democratic and Republican interests held views that were highly different from the general population on ideologically charged issues, such as gay marriage and affirmative action. Although just 17 percent of noncontributing survey respondents supported gay marriage, a whopping 67 percent of those contributing to Democratic interests did. Republican donors were more representative, with 7 percent supporting such unions. Twenty-one percent of noncontributors support preferential hiring of minorities, while 35 percent of donors to Democratic causes and just 3 percent of Republican causes did. Contributors to both sides of the partisan divide were equally unrepresentative of noncontributors on the issue of providing illegal immigrants with a process for obtaining citizenship. While 48 percent of the general population favored such a process, 74 percent of Democratic donors and 25 percent of Republican donors did. Donors to Democratic interests were more ideologically distinct from noncontributors than donors to Republican interests on the issues of raising taxes, abortion, and women’s place in the home. The attitudes of contributors to Republican interests were more distinct on the issues of universal health coverage, devoting more government resources to the war on terror, and increasing spending on aid to the poor. Overall, it is difficult to say which group of donors is more ideologically distinct. What is quite clear from the data in Table 5 is that donors as a group continued to be extreme in their ideological commitments in 2008 even if they were more representative in terms of other factors. If it is true that donors influence the policy preferences of elected officials— either through quid pro quo transactions or by simply bending their ear—then the future promises even more ideological polarization among political elites. CONCLUSION We find little evidence to suggest that the 2008 donor pool was any more representative of the general public than it was in 2004. Contributors to Democratic interests were slightly more representative in terms of age and income, but these were not the most significant predictors of donating in 2008; education and ideological extremism were. With respect to these attributes, donors to Democratic interests were just as unrepresentatative—or even more so—of the general public in 2008 as they were in 2004. Our analyses do suggest that donors to Republican candidates and party committees were slightly less representative than those giving to Democratic interests. That said, these findings should not obscure the overall message emerging from our analysis: that donors in general continue to be a highly distinct group of individuals. Campaign Contributions and Contributors in the 2008 Elections 57 Downloaded by [Princeton University] at 08:34 03 January 2012 NOTES 1. FEC; Center for Responsive Politics. 2. Available at http://people-press.org/report/436/obama-mccain-july. 3. These numbers reflect the number of contributions that were more than $200 since only these trigger FEC reporting requirements. 4. Campaign Finance Institute press release (January 2, 2010). 5. Available at http://whitehouseforsale.org (accessed January 15, 2010). 6. Campaign Finance Institute press release (January 8, 2010). 7. We note that this item does not ask candidates to distinguish between levels of office, so it is an aggregate measure of giving to any candidate, party, or group organization, including, potentially, federal and subnational committees. The NES also does not ask about the amount of contributions, so it is not possible to compare small and large donors. 8. According to the U.S. Census, the adult population grew by about 13 million Americans between 2004 and 2008. 9. In 2008, the NES used a split sample to test new question wording. Among others, it tested new versions of their political and campaign interest questions. Instead of excluding the half of the sample that was asked the new version of the campaign interest question, we replaced all instances in which the new version of the campaign interest question was asked with a constant value (in this case, the mean response to the old version of the question) and simultaneously created a dummy variable which was coded ‘‘1’’ for all cases in which this replacement was made. Including the dummy variable in the analysis allows us to interpret the coefficient for the campaign interest variable as the substantive effect of the variable for the cases where a respondent was asked the old version of the campaign interest variable. For clarity of presentation, we have omitted the dummy variable from the table. This method is an elegant way of addressing missing data problems, but it also offers an excellent way of dealing with our situation. 10. The base category is ‘‘Independent.’’ If the ‘‘Strong Democrat’’ dummy variable is omitted instead, the model reveals that the odds of a strong Democrat giving were significantly higher than for any other group. 11. This figure could not be created with the post-election weights. It is still useful for determining which groups of respondents were underrepresented among donors in 2008, but the figure should not be used to draw conclusions about how the ideological composition of the electorate differed from previous years. 12. The NES ideology scale ranges from 1 (extremely liberal) to 7 (extremely conservative). A one-way ANOVA test reveals the difference in means is highly statistically significant (at the p < .001 level). REFERENCES Francia, Peter, John Green, Paul Herrnson, Lynda W. Powell, and Clyde Wilcox. (2003). The financiers of Congressional elections: Investors, ideologues, and intimates. New York: Columbia University Press. Green, Joshua. (2008). The amazing money machine. The Atlantic, 301(5). Retrieved January 3, 2011, from http://www.theatlantic.com/doc/200806/obama-finance Malbin, Michael J. (2009). Small donors, large donors and the Internet: The case for public financing after Obama. Campaign Finance Institute Working Paper. Retrieved from January 3, 2011, from http://www.cfinst.org/president/pdf/ PresidentialWorkingPaper_April09.pdf McDonald, Michael P. (2009). The return of the voter: Voter turnout in the 2008 presidential election. The Forum, 6(4). Retrieved January 3, 2011, from http:// www.bepress.com/forum/vol6/iss4/art4/ Panagopoulos, Costas and Daniel Bergan. (2006). Contributions and contributors in the 2004 presidential election cycle. Presidential Studies Quarterly, 36(2).