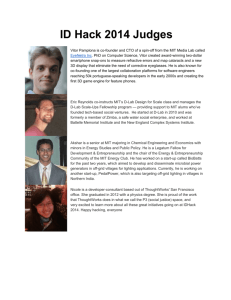

Visibility of the MIT Entrepreneurship Ecosystem:

advertisement