LIBRARIES ARCHNS -I JUN 15

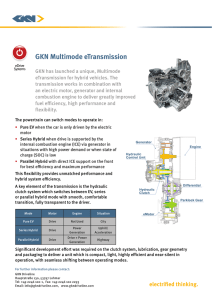

advertisement