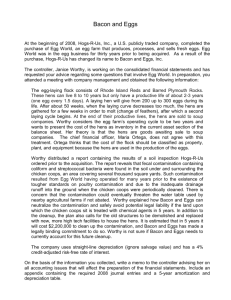

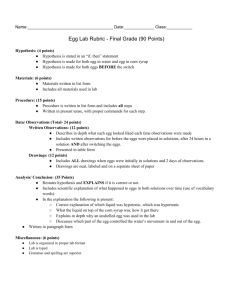

The Happy Hen on Your Supermarket Shelf Jane Kotey

advertisement