A Golden Age of Philanthropy Still Beckons: Technical Report

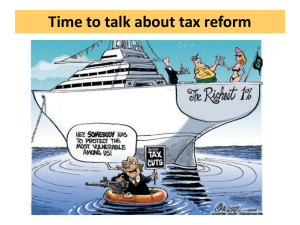

advertisement