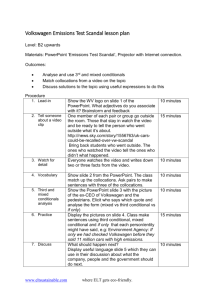

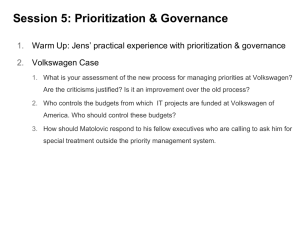

A SOCIAL MEDIA CASE STUDY INCORPORATING

advertisement