S R E P

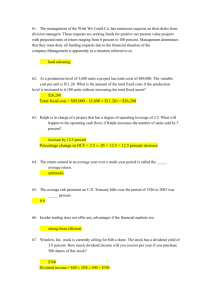

advertisement