Document 10868981

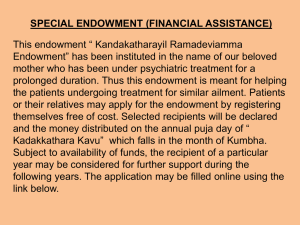

advertisement