Evolution of Telecom and the Ohio Template for Reform: 2009 The

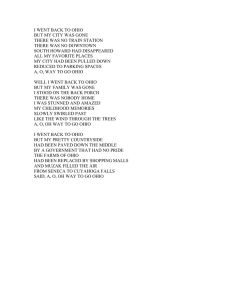

advertisement