Natural Capital Index of Canada Kazi N. Islam

advertisement

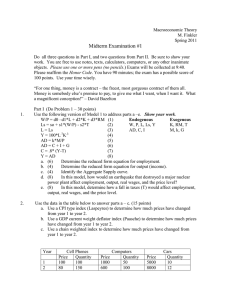

April 28, 2006 Natural Capital Index of Canada : A barometer of the stock of natural resources Kazi N. Islam Economist Statistics Canada 7-E, R. H. Coats Bldg 120 Parkdale Avenue Ottawa, ON K1A OT6 Kazi.islam@statcan.ca ii Table of Contents Abstract iii Section 1: Introduction 1 Section 2: Similar Studies 2 Section 3: Data 4 Section 4: Methodology 6 Section 5: Natural Capital Index of Canada 9 Section 6: Natural Capital Index for the Provinces and Territories 18 Section 7: Conclusion 20 Appendix A: Figures—Index for the Provinces and Territories 22 Appendix B: Reserve and Present Value 32 Appendix C: Example of Index Construction 34 References 36 iii Abstract Canada, the second largest country in the world by landmass after Russia, is endowed with a huge amount of natural capital--which refers to the land, the ecosystem and the natural resources such as oil and gas and gold. Conservation and replacement or regeneration of this natural capital play a crucial role for sustainable development—development of the current generation without compromising the needs for future generations. This paper has developed an index that can be used to track the trend in natural capital. Currently Statistics Canada’s natural capital basket consists of 16 resources. The stock of the resources and the present value of the stream of rents that may be generated from the stocks are the basis of the newly developed natural capital index. The index is necessary to gauge the trend in aggregate natural capital stock. Because the resources are measured using different units—gold is measured in kilograms and oil is measured in cubic meters. Even if the resources could be converted to the same unit they cannot be added as long as their net prices/rents differ. Therefore, physical quantities or resources cannot be added together. The index can not only overcome this measurement problem but also works like a barometer that can be used to track the state of natural capital. First, the paper has modified the standard Laspeyres, Paasche and Fisher quantity index formulas to apply the stock and the present value of the rent data. Data for the period from 1980 to 2005 are used to calculate the chained version of each of these indexes. The chain-Fisher index is mainly used for explaining the trends in the natural capital index as it is superior to the other formulas. From 1990 to 2005, Canada’s natural capital had depleted by 13%, which can be a source of concern for sustainable development. During the same period, Canada’s population increased by 18%--from 27 million to 32 million. Further analysis reveals that much of this depletion is due to the drop in the stocks of minerals and timber. This paper has also provided the natural capital index for the provinces and territories—as they are the owners and stewards of much of the natural capital in Canada. Thus, policymakers as well as politicians may find the index useful for monitoring changes in resource stocks and developing appropriate sustainable development strategies for their jurisdictions. 1 Natural Capital Index of Canada : A barometer of the stock of natural resources 1. Introduction Canada, the second largest country in the world by landmass after Russia, is endowed with a large amount of natural resources such as oil and gas and gold. These resources are the major components of natural capital--which refers to natural resources, the land which provides space on which to live and work, and the ecosystems that maintain clean water, air and a stable climate. In the past, natural capital was considered a free gift of nature, in abundant supply. With industrialisation and increased world population, the world demand for natural capital has increased rapidly. As a result, in recent years resource based economies such as Canada have been extracting and exporting natural capital at an increasing rate. By doing so, Canada--especially its provinces such as Alberta and Newfoundland--are collecting substantial natural resource royalties. Most of these royalties are spent to increase the welfare of the current generation. However, rapid depletion of natural capital might be detrimental for sustainable development--development of the current generation without compromising needs of future generations. From a capital perspective, sustainable development requires nondeclining per capita national wealth by replacing or conserving the sources of that wealth—the stocks of produced, human, social and natural capital. For conservation, it is essential to have time series data on depletion as well as addition of the natural capital. Statistics Canada, through its natural resources and stock accounts (NRSA) initiative, has been gathering time series data on extraction and reserve for natural gas, crude oil and timber since 1961. In later years, reserves of other resources such as gold and coal were added to the NRSA as they became economically and technologically feasible to extract: currently there are 16 categories of resources. These reserves, known as established reserves, are expected to generate a stream of future rents—the difference between the market value of a resource and its extraction costs. The present value1 of potential rents that can be derived from the reserves are often used by nations to gauge their natural capital riches or wealth. In 2005, per capita net worth of Canadians stood at $166,000 of which more than $66,000 or 40% were derived from natural capital, and the remaining 60% were derived from produced assets such as machinery and equipment, and buildings and bridges.2 In recent years, the natural resource wealth has been growing faster than the other types of wealth. This is mainly due to the higher resource prices stemming from the increased world demand. The 1 The present value (PV) is the product of rent and reserve life, which is the ratio of reserve to production. Thus, the PV is affected either by a change in rent or reserve or both. A note on the derivation of present value of rents is shown in Appendix B. 2 In 2005, per capita net worth excluding natural resource wealth was $137,300. Natural capital wealth is the sum of natural resource wealth and wealth generated from the land. For details, see, The Daily <http://dissemination.statcan.ca/Daily/English/060317/d050317a.htm> 2 growth in price immediately affects the growth in rents and thereby the present value of the resource stock. However, the impact of price on the stock of the resource is often inconclusive. The price increase is likely to have dual effects on the stock: a) a higher price would provide an incentive for exploration and drilling activities that might result in opening new mine sites, thereby increasing the level of reserves, and b) on the other hand, the higher price may increase profit and accelerate the level of extraction, which would reduce the reserve. The following example demonstrates the relationship among price, present value and reserve growth rates. Figure 1: Crude oil--growth rates of price, present value and reserve 120 100 80 growth % 60 40 20 20 05 20 04 20 03 20 02 20 01 20 00 19 99 19 98 19 97 19 95 19 96 19 94 19 93 19 91 19 92 19 90 19 89 19 88 19 87 19 86 19 85 19 83 19 84 19 82 19 81 19 80 0 -20 -40 -60 Price PV Reserve Figure 1 indicates that the relationship between crude oil price and its present value is highly positive, whereas the relationship between the growth rate of price and the growth rate of reserve is negative. From 1998 to 2001, all the three growth rates experienced high degrees of volatility due to a sharp increase in reserve resulting from offshore oil in Hibernia, located 315 kilometres east-southeast of St. John's, Newfoundland. Although the Hibernia site was discovered in 1979, the resource was not considered a reserve until 1998, when extraction became economically and technologically feasible. Similar patterns have been often observed across the natural resources. As a result, the trend in the nominal value of the wealth inadequately reflects the trend in the quantity stock, and cannot be used as a yardstick for conservation or sustainable development. Although the reserve data would reflect the change in net stocks due to 3 price as well as technological changes, these data are often confidential at the provincial and territorial level. Also, when looking at each resource individually, it is hard to appraise the overall change when the reserve of one resource such as gold declines and the reserve of another resource such as natural gas increases. Mainly because gold is measured in kilograms and natural gas is measured in cubic meters. Even if two or more resources are measured using the same unit, their physical stocks cannot be added unless their average rents are identical. Thus, an index showing the physical quantity of the remaining stock is needed for tracking the natural resources stocks. The natural capital index (NCI), like other quantity indexes such as the GDP volume index, is a weighted average of the remaining quantities of natural resources, where the PV of rents is used as weights. The index would reflect period-over-period change in the stock without revealing the stock levels. Clearly the natural capital index, a unit-free measure, is the best choice in tackling both the confidentiality and comparability concerns. Certainly, the index will enrich the existing information about individual resource stocks, and provide a snapshot of Canada’s natural capital stock for the policymakers and politicians as well. In particular, the index can be used for the following purposes: 1) to track year-over-year change in aggregate natural capital both at the federal as well as provincial and territorial levels, 2) to pin down which resource is depleting faster than it is being replenished, and therefore conservation, regeneration or replacement are warranted, 3) to compare inter-regional performance, i.e., which provinces or territories are depleting or replenishing their resource stocks at what rate? In a word, the index would act like a barometer, which can be used without knowing much about its construction. Notably, the marginal cost of updating the index would be very low, since the index can be considered a by-product of NRSA, which compiles the ingredients of the index: resources reserves and their present values. The index is expected to generate renewed enthusiasm among Canadians, especially those who are concerned about sustainable development. With this aim in mind, the rest of the paper is organized as follows: Section 2 briefly reviews the experiences of Australia and the Netherlands; Section 3 looks at the availability of data; Section 4 derives and discusses the methodology of constructing the NCI; Section 5 shows the NCI of Canada and its implications; Section 6 examines the NCI for the provinces and territories; and the last section makes concluding remarks. 4 2. Experiences of Australia and the Netherlands The number of empirical studies related to the natural capital index is very limited: so far, the literature suggests that Australia and the Netherlands have conducted empirical studies in this regard. In 2001, the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) introduced an experimental real national balance sheet that excludes the effects of price change.3 The ABS has derived chain volume estimates for subsoil assets, timber and land for the period 1992 to 2000. The constant price balance sheet was then used to evaluate the composition of non-financial assets over time and to construct an index of real growth of different assets in the balance sheet. In Australia, the chain volume estimates of subsoil assets such as oil and gas and gold increased close to 50% from 1992 to 2000.This was due to new discoveries exceeding extractions. Standing timber fell by 3.8% over the same period. The Netherlands, through its critical natural capital indicator initiative, has attempted to develop three types of indicators: the indicator for stocks of natural capital, general natural capital index and a protected areas index.4 Indicators for stocks of natural capital are developed to identify and analyse the most important and critical functions of the selected stocks of natural capital--fresh water, soil, wetlands, forest, fish and biodiversity. Indicators are developed based on a set of operational criteria for the selection of the “most important” functions. Also, an aggregated “total indicator” for the whole stock of natural capital is produced. The second set of indicators, known as the general natural capital index, is defined as the product of the remaining area (ecosystem quantity) and its quality (ecosystem quality). Ecosystem quantity refers to the percentage of remaining ecosystem in a particular region and ecosystem quality is the ratio between current state of the ecosystem and the baseline state. The natural capital index ranges from 0% to 100%: 0% means that the entire ecosystem has deteriorated either because there is no area left or that the quality is 0%, or both, while 100% means the entire ecosystem is intact and is at its maximum value. Finally, an index to capture the protected areas was developed by using a number of criteria. These criteria, however, are partly based on scientific grounds and partly on policy targets. Thus, what certain countries may define as “critical” on a national level may not be “critical” on a global/universal scale. The approaches taken by the two countries are quite different. The ABS index is based on the theory of quantity index, whereas the Netherlands approach is based on a pre-defined scale or criterion. The ABS approach is similar to other quantity indexes such as the GDP volume index. The ABS report, however, has not published the natural capital index as 3 4 th For details, see Developments in Australian Wealth Statistics, 30 Annual Conference of Economists, Perth. Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2001. For details, see Towards a Method to Estimate Critical Natural Capital, Discussion Paper for the second meeting of the CRITINC-project, France, Wageningen University & Research Centre, Department of Environmental Sciences, 2000. 5 such. The index has been used to calculate real growth rate of natural resources. Given the availability of data, as shown in the next section, Statistics Canada is better positioned to produce various quantity indexes, which can be used independently to track the trend in natural capital stock. 3. Data Ideally the natural capital basket should include all non-produced assets such as those identified in the System of Integrated Environmental and Economic Accounting (SEEA)—the internationally agreed-upon handbook of national accounting--as shown in the following table. Table 1: Components of Natural Capital 1.Natural resources o Mineral and energy resources o Soil resources o Water resources o Biological resources Timber resources Crop and plant resources other than timber Aquatic resources Animal resources other than aquatic 2.Land and surface water o Land underlying buildings and structures o Agricultural land and associated surface water o Wooded land and associated surface water o Major water bodies o Other land 3.Ecosystems o Terrestrial ecosystems o Aquatic ecosystems o Atmospheric systems Source: United Nations, 2003, Handbook of National Accounting, Integrated and Environmental Economic Accounting, SP/ESA/STAT/SER.F/61/REV.1 (final draft), table 7.2. Several of the aforementioned items such as ecosystems and water are yet to be included in the Natural Resources and Stock Accounts (NRSA) 5—Statistics Canada’s natural capital database. The primary reason is the lack of data, which are hard to collect if a resource is not economically and technologically feasible to extract. Conceptual 5 Detailed discussion of the derivation of the NRSA is beyond the scope of this paper. For further information on the methodology, please refer to Statistics Canada, 1997, Econnections, Catalogue no. 16-505-GPE, Ottawa. 6 complexities as well as financial constraints are also major obstacles for bringing additional items into the NRSA. Currently the NRSA provides the physical and monetary data on energy, mineral resource, agricultural land and timber as shown in the following table. Table 2: Available Data Category Name Year Energy Resource Natural Gas Crude Oil Crude Bitumen Bituminous Coal Sub-Bitumen Coal and Lignite 1961 to 2005 1961 to 2005 1967 to 2005 1975 to 2005 1975 to 2005 Mineral Resource Gold-Silver Nickel-Copper Copper-Zinc Lead-Zinc Iron Ore Molybdenum Uranium Potash Diamonds Timber Agricultural Land 1978 to 2005 1976 to 2005 1975 to 2005 1978 to 2005 1975 to 2005 1977 to 2005 1975 to 2005 1975 to 2005 1998 to 2005 1961 to 2005 1920 to 2005 Timber Land Note: For most resources, the reserve and the corresponding present value data for 2004 and 2005 are estimated, as there are more than two years of time lag in getting the actual data. Data for some mineral resources such as copper and zinc are not available individually as these minerals are often produced from the same mine site, and the collected data only represent combined extraction costs. Agricultural land data are collected every five years, through the census of agriculture, and estimated for the interim period. Similarly, timber data are also estimated for most of the years, as they are not collected annually. Table 2 shows that all the data series except diamonds are available from 1978 to 2005. Diamonds became an established reserve in October 1997, and annual data are available since 1998. Although offshore oil and gas also came on stream in 1998 or later, these resources are merged with onshore oil and gas respectively as they are measured using the same units. Also, in a few cases, the present value of resources in 1978 and 1979 is negative, which are not unusual because the extraction costs in the initial years often exceed the total revenue. As a result, the natural capital index is calculated using the quantity (reserve) and present value data from 1980 to 2005. There are several widely-used quantity indexes such as the Laspeyres, the Paasche and the Fisher. The next section discusses and modifies these indexes so that the available data can be applied directly. 7 4. Methodology Theories of index numbers are well-established in economic literature and widely used to measure various economic phenomena such as the consumer price index and the GDP deflator. 6 The natural capital index is also based on the same theory, and therefore, the index would have sound theoretical ground. However, there are different types of indexes, and each one of them has pros and cons. Using the most important ones-namely the Laspeyres, Paasche, and Fisher quantity index--would enable us to understand the trend of Canada’s natural capital. 4.a. The Laspeyres quantity index: For the Laspeyres quantity index, a pre-selected base year’s prices are used as weights. Symbolically the index can be written as follows: n Q L q ti p ti ∑ i = =1 n q ∑ i =1 i t p i t L L L L L L L L L L L L L1 where Q L = the Laspeyres quantity index for the period t using the base period 0, p = the price series, and q = the quantity series. i = refers to the ith item, and n is the total number of items in the basket. For simplicity , ' i' would be dropped from here on. Since the NRSA data are available in quantity and value (V=pq, or price multiplied by quantity) forms, through algebraic manipulation the above formula can be rewritten in a more usable form. Q L ∑ qt p = ∑q p 0 0 where V0 ⎡q ⎤ 0 = ∑ ⎢ q t ⎥q ⎣ 0 ∑q ⎦ 0 0 p0 ⎡q ⎤ p0 = ∑ ⎢ q t ⎥V ⎣ 0 ⎦ ∑V 0 LLL 2 0 = present value of the resource in the base year Equation 2 is used to calculate the fixed-base Laspeyres index. This formula is easy to interpret and additive—if separate indexes are calculated for subgroups such as minerals and energy, then they can be added to get the aggregate natural capital index. However, 6 For details, see, Allen, R.G.D. 1975, Index Numbers in Theory and Practice, Aldine Publishing Company, Chicago. 8 the formula is highly dependent upon the selection of the base year. A selected base year loses its relevance for the distant years as the prices change over time. Setting base year in the middle changes the meaning of the index as the pre-base year period index becomes the Paasche type, which uses the current year as a weight, and the post-base year period index becomes the Laspeyres type. A more appropriate version is the chained Laspeyres index, where every preceding year is used as a base year for the current year. To calculate the chained index, first the yearover-year index (also known as unchained index) is calculated using the following formula: the unchained Laspeyers quantity index, QucL = ∑ qt pt ∑ qt pt −1 −1 −1 = ⎡q ⎤ ⎥ qt −1 pt −1 ⎣ t −1 ⎦ ∑ ⎢q t ∑ qt −1 p t −1 = ⎡q ⎤ ⎥Vt −1 ⎣ t −1 ⎦ LLLL3 ∑ ⎢q t ∑Vt −1 In other words, to calculate the unchained Laspeyres quantity index, one needs to calculate the weighted average of the quantity relatives where the previous period’s price (pt-1) is assigned as the weight. Using the value from formula 3, the chained index can be calculated as follows: The chained Laspeyres index QcL = 1 × (QucL )period 2 × (QucL ) period 3 L (QucL )periodt LLLLLLLLLLLL 4 The chained Laspeyres index is simply the product of unchained Laspeyres indexes, where the index for the starting period (also known as the reference period) is assumed to be 1 or 100%. Because of its multiplicative form, it is easy to shift the reference year without losing the trend. Even in the chained form, the Laspeyres index usually overestimates the actual trend. To avoid this shortcoming, Paasche proposed an index which uses the value of current period as weight. 4.b: The Paasche quantity index In a time series, if the final or end year’s price is considered as weight, then the index becomes the Passche quantity index as shown in the following formula. 9 = QP ∑ qt pt ∑ q pt ∑ qt pt = ⎡q ⎤ ∑ ⎢ q0 ⎥ qt pt ⎣ t⎦ 0 ∑Vt = ⎡q ⎤ ∑ ⎢ q0 ⎥Vt ⎣ t⎦ LL 5 where Q P is the Paasche quantity index, and Vt = present value of the resource in the current period The unchained version of equation 5 is, QucP = ∑ qt pt = ∑ qt pt ∑ qt pt ∑ ⎡ qt ⎤ q p t t ⎢ q ⎥ −1 −1 ⎣ t ⎦ = ∑Vt ⎡q ⎤ ∑ ⎢ qt −1 ⎥Vt ⎣ t ⎦ LLLLLL 6 Similar to the chained Laspeyres index, the chained Paasche index can be calculated using the following formula: QcP = 1 × (QucP )period 2 × (QucP ) period 3 L (QucP )periodt LLLLLLLLLLLL 7 Although the chained Laspeyres and the chained Paasche indexes are more relevant than the fixed based ones, both of them typically suffer from a bias. If the price relatives (pt/pt-1) and the quantity relatives (qt/qt-1) are negatively correlated, then the underlying change is overstated in the Laspeyres index and understated in the Paasche index, i.e. creates upward and downward biases respectively. The opposite happens if the price and quantity relatives are positively correlated. To resolve this problem, Irving Fisher proposed an index that averages the two indexes. 4.c: The Fisher quantity index: The Fisher quantity index is the geometric mean of the Laspeyres and Paasche indexes, and can be written as follows: 10 ⎡q ⎤ Q F = Q ×Q = L P ∑ ⎢ q t ⎥V ⎣ 0 ⎦ ∑Vt 0 ∑V 0 × ⎡q ⎤ ∑ ⎢ q0 ⎥Vt ⎣ t⎦ LLLLL8 or the unchained version F QuC = QCL × QCP = ⎡q ⎤ ⎥Vt −1 ⎣ t −1 ⎦ × ∑ ⎢q t ∑Vt −1 ∑Vt ⎡q ⎤ ∑ ⎢ qt −1 ⎥Vt ⎣ t ⎦ LLLLL 9 The chained Fisher index QcF = 1 × (QucF ) period 2 × (QucF )period 3 L (QucF ) periodt LLLLLLLLL10 The Fisher index not only removes the bias but also fulfills the time and factor reversal tests of index numbers—important criteria for an ideal index formula. The time reversal test requires that if the base and current periods are interchanged, the formula would produce the reciprocal of the original index, i.e. 1/time-interchanged-index = original index. The factor reversal test needs that the product of price and quantity indexes will produce the value index, i.e., P01Q01=V01. The main weakness of the chained Fisher index, like other chained indexes, is its nonadditivity, i.e., index calculated using components do not add up to the aggregate index. Despite this limitation the Canadian System of National Accounts is currently based on the chained Fisher index because of its superiority over the other index. In order to produce a consistent and coherent natural capital index, the chained Fisher index is mainly referred in this paper. The next section exhibits the natural capital index of Canada. 11 5. Natural Capital Index As mentioned in section 3, Canada’s natural capital basket is based on the NRSA data on reserves and their present value of the reserve. For a number of reasons, the PV data sometimes become zero, which makes it difficult to select an appropriate reference year. If price drops below a threshold level, rent could become zero, and thereby the PV. In fact, a few zero values are observed in the NRSA data set for 1978 and 1979. In 1980, however, all the series had positive numbers; therefore, 1980 is used as the reference year. Figure 1: The Natural Capital Index of Canada 120 100 % 80 60 40 20 4 3 2 1 0 5 20 0 20 0 20 0 20 0 20 0 20 0 8 9 7 6 Chained Paasche 19 9 19 9 19 9 19 9 5 4 Chained Laspeyers 19 9 3 19 9 19 9 1 0 2 19 9 19 9 9 Laspeyers_1980=100 19 9 19 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 8 19 8 19 8 19 8 19 8 19 8 19 8 19 8 19 8 19 8 0 0 Chained Fisher Figure 1 indicates that the Laspeyres index overestimates the trend whereas the Paasche index underestimates the trend, especially when the indexes diverge from each other. For almost a decade starting from 1981, the natural capital index had been steady around 97%, implying that the extractions and additions had been canceling each other. The index dropped slightly in 1998, and bounced back to 100% again in 1989 mainly due to a huge increase in the physical stock of potash. Since 1990, the index had steadily declined, and in 2005 the index stood at 87%, or a 13% drop from the 1990 level. This drop implies that Canada’s natural capital stock has been declining almost 1% each year since 1990. In other words, addition or regeneration of natural capital is about 1% less than the rate of depletion, and this gap can be a source of concern. In order to unearth 12 the underlying reasons for this drop, the various subcomponents of the natural capital are examined. 5.1 Subindexes As mentioned in the data section, Canada’s natural capital basket consists of four major components--energy, minerals, timber and agricultural land. Individual index for each of these components would provide further insights about the drop in the overall index. The following graph depicts the relative importance of the components in the creation of expected wealth overtime. Figure 2: The Percentage Share of Each Component—Present Value ($) 120 100 Agricultural land 80 % Minerals 60 Timber 40 20 Energy 20 05 20 04 20 03 20 02 20 01 20 00 19 99 19 97 19 98 19 96 19 95 19 94 19 93 19 92 19 91 19 90 19 89 19 87 19 88 19 86 19 85 19 84 19 83 19 81 19 82 19 80 0 Figure 2 shows that in 2005, the energy resource wealth accounted for around 50% of natural resources wealth followed by timber (29%), minerals (11%) and land (9%). In the mid-1980s, energy accounted for around 60% of Canada’s natural resource wealth. The oil crisis of the 1970s had increased energy prices, which created incentives for prospecting for new sites. During the 1990s, however, timber’s share exceeded that of energy perhaps due to reduced energy prices. The relative share of agricultural land, as expected, had not changed much. The relative share of mineral resources had fluctuated 13 quite a bit. This is mainly because of volatility of mineral prices. Also, the opening and closing of mine sites occur more frequently than the other components of the natural resources. The natural capital index of each of the components is depicted below. 5.1 Energy Index: The NRSA consists of non-renewable energy resources: natural gas, coal, crude oil and crude bitumen. Excessive consumption of these fossil fuels has serious implications for sustainable development as the combustion of fossil fuel emits much of the greenhouse gases that are partly responsible for global warming and climate change. Figure 3: Energy Index 120 100 80 60 40 20 4 3 2 1 0 9 8 7 5 20 0 20 0 20 0 20 0 20 0 20 0 19 9 19 9 6 Chained Paasche 19 9 4 3 5 19 9 19 9 19 9 2 19 9 1 0 9 Chained Laspeyers 19 9 19 9 19 9 19 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 0 8 19 8 19 8 19 8 19 8 19 8 19 8 19 8 19 8 19 8 1 0 Chained Fisher Figure 3 indicates that the energy index had slightly increased until the mid-1980s, and had started to decrease after 1985 and reached its nadir in 1997, at close to 84%. Much of this can be attributed to the lower energy prices in the early 1990s, as it not only discouraged exploration and drilling in Canada but also made the already discovered resources unprofitable to extract thereby decreasing the stock.7 There was a jump in the index in 1998, and by 2000 the index reached its peak at 107%. In the recent years, the index has been hovering around 100%. Thus, the energy resource reserve did not become a significant factor to the 13% drop in the aggregate index. The 7 In the mid-1990s, the price of crude oil was hovering US$18 per barrel as compared to US$30 per barrel in the late 1970s, and US$60 per barrel in the recent years. 14 recent increases in price as well as technological improvement have enabled businesses to tap additional resources, especially crude bitumen (tar sands) as shown in the following figure. Figure 4: Energy index by resource type To calculate the index for one item, the PV series is irrelevant as there is no need to assign any weight. The item itself will have the full weight; therefore all the index number formulas mentioned in section 3 converge to a simple quantity ratio (qt/q80). Although these simple ratios cannot be added together, they can be used to identify the depletion rate of the resource. 600 500 400 300 200 100 4 3 2 1 0 9 5 20 0 20 0 20 0 20 0 20 0 20 0 8 19 9 7 Crude bitumen 19 9 5 4 6 19 9 19 9 19 9 3 1 2 Crude oil 19 9 19 9 19 9 0 9 Natural gas 19 9 19 9 7 6 5 4 3 2 0 8 19 8 19 8 19 8 19 8 19 8 19 8 19 8 19 8 19 8 19 8 1 0 Coal The above chart indicates that the biggest jump occurred in crude bitumen. In 1999, the crude bitumen index reached at 566%. Alberta’s oil sands are the main source of this reserve. The crude oil and natural gas stock has been steadily declining, while the coal index has been hovering slightly above 100 since 2002. After several years of steady depletion, the reserve increased rapidly in 1998, with the addition of offshore oil in Hibernia, when the index reached 78 from 62 in the previous year. 15 5.2 Mineral Index: The NRSA data indicate that the present value of minerals such as gold and molybdenum became zero few times. Much of this has occurred due to volatile resource prices and short life expectancy of mine sites. As a result, the mineral index is more volatile than any other components as shown in the following figure. Figure 5: Mineral Resource Index 120 100 % 80 60 40 20 Chained Laspeyers Chained Paasche 20 05 20 03 20 04 20 02 20 01 19 99 20 00 19 98 19 97 19 95 19 96 19 94 19 93 19 91 19 92 19 90 19 89 19 87 19 88 19 86 19 85 19 83 19 84 19 82 19 81 19 80 0 Chained Fisher Figure 4 shows that from 1980 to 1988, the index had decreased by 12%. In 1989, the index jumped to 105, mainly because of a rapid increase of the potash reserve. The index remained around 100 until 1996. It started to decline thereafter, and in 2005 the index dropped to 65%. This 35% drop may have contributed significantly to the overall drop in the index, as the mineral resource share in the overall index is around 11%8. Due to the high commodity prices in the recent years, the depletion rate became high; however, there was no big discovery except diamonds in the recent years. The following chart and table indicate the index for each item in the mineral resource basket. 8 Although the chain index is non-additive, the approximation indicates that the mineral index might have contributed around 4% (.35*.11) of the drop in the overall index. 16 Gold-Silver Iron ore Year 1980 1981 1982 1983 1984 1985 1986 1987 1988 1989 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 GoldSilver 100 112 118 201 211 246 284 331 355 321 304 278 268 264 303 312 325 277 267 254 224 202 197 186 169 142 NickelCopper 100 95 92 92 90 88 84 82 78 77 72 71 70 67 67 73 70 64 71 62 60 54 51 49 41 39 Nickel-Copper Molybdenum CopperZinc 100 93 101 97 93 85 77 77 75 72 68 69 62 54 50 48 54 51 42 40 37 32 28 24 22 18 Lead -Zinc 100 97 94 94 94 89 83 77 75 74 64 58 54 48 47 45 42 31 24 21 18 13 10 8 7 6 Iron ore 100 76 76 81 81 82 82 82 82 83 83 83 83 83 83 83 83 83 21 21 21 21 21 21 21 20 Copper-Zinc Uranium Molybd enum 100 92 85 80 66 60 57 42 38 38 36 32 30 30 27 24 25 26 23 22 22 18 16 14 20 18 Uranium 100 77 85 75 59 59 60 58 56 56 66 68 69 70 68 102 105 95 99 95 99 103 100 98 95 92 20 04 20 02 20 00 19 98 19 96 19 94 19 92 19 90 19 88 19 86 19 84 19 82 500 450 400 350 300 250 200 150 100 50 0 19 80 % Figure 6: Individual Mineral Resource Index Lead-Zinc Potash Potash 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 115 338 338 338 338 338 338 338 338 338 338 338 338 338 431 431 430 429 Diamon ds 100 96 80 76 68 250 231 213 17 The above figure and the associated table show the trend in individual mineral resource reserve. No wonder why the minerals resource index had dropped by 35%, as most of the mineral reserves except gold and potash had dropped markedly—for example, Lead-Zinc dropped 84%, and Molybdenum dropped 82%. In 1998, with the activation of the initiation of the Ekati diamond mine-- located about 300 kilometers northeast of Yellowknife, Northwest Territories--Canada became a diamond producer country. Until 2003, the reserve continued to decline because of extraction. In 2003, the Diavik mine, located 300 km northeast of Yellowknife, gave a boost to the reserve. However, the share of diamonds in the total mineral resource basket is insignificant. 5.3 Land Index Ideally land assets should include land associated with residential and non-residential buildings, agricultural land and land used for recreation or environmental protection such as parkland. Currently, only the agricultural land is included in the NRSA data base, and the calculated index is shown below. Figure 7: Land Index 110 100 90 80 70 60 50 40 30 20 10 20 05 20 04 20 03 20 02 20 01 20 00 19 99 19 98 19 97 19 96 19 95 19 94 19 93 19 92 19 91 19 90 19 88 19 89 19 87 19 86 19 85 19 84 19 83 19 82 19 81 19 80 0 Agricultural land The quantity of agricultural land is the only item in this basket; thus, the index reflects the quantity relatives. The index remained close to 100% till 1996. In 2005, the index dropped to 97%. This 3% loss may be attributed to the increased level of urbanization in 18 recent years. Since the relative share of agricultural land in the overall natural capital is only 9%, the impact of this small decline of land on the overall index is insignificant— perhaps around 0.27%. If the residential and urban lands were added the index might remain the same–close to 100%, as the geographical boundary of a country remains the same unless there is a serious land erosion or land is taken by or given away to the another nation. 5.4 Timber Index Timber plays a significant role in sustaining environment and ecosystems. Timber is conducive in maintaining a stable climate; therefore, special attention should be given to this capital for sustainable development. According to the NRSA timber assets are those timber stocks that are capable of producing a merchantable stand within a reasonable period of time, that are physically accessible and that are not reserved for purposes other than harvesting. Figure 8: Timber Index 110 100 90 80 70 60 50 40 30 20 10 20 05 20 04 20 03 20 02 20 01 20 00 19 99 19 98 19 97 19 96 19 95 19 94 19 93 19 92 19 91 19 90 19 88 19 89 19 87 19 86 19 85 19 84 19 83 19 82 19 81 19 80 0 Timber Figure 6 represents the index for timber, where timber is the only item in the basket. The index indicates a relatively high rate of depletion of timber. By the end of 2005, the index dropped by 11% from the 1980 level. Given the importance of timber in Canada’s natural 19 capital basket, this 11% drop may have contributed significantly to the overall drop in the index.9 From the above discussion it is clear that Canada’s natural capital index has been declining since 1990. Clearly per capita natural capital has been decreasing even faster: Canada’s population in 1989 was around 27 million, and in 2005 the population reached above 32 million. Thus, for sustainable development, more conservation or replacement or regeneration may be needed. In Canada, the provincial and territorial authorities are the owners and stewards of much of the natural resources. Also, the changes in the stocks of natural capital tend to be specific or localized. With this in mind, the provincial and territorial natural capital indexes are explored in the next section. 9 In 2005, the share of timber was 29% of the total PV of resources. Thus, the drop in timber index might have contributed 3.2% of the drop in the overall index, which dropped by 13% in 2005 from 1990. 20 6. Provinces and Territories Canada is constituted of 10 provinces and 3 territories, and resource endowments are quite divergent in these 13 regions. The regional data are scarcer than the national data. For some metals such as iron and zinc, data are available only at the national level although the resources belong to several regions. Also, 2004 and 2005 estimates are unavailable for the provinces and territories. As a result the latest data point is 2003, as shown in the following table. Table 2: Data for the Provinces and Territories N F L D P E I N S N B Q U E O N T Nat Gas 1961 to 2003 X M S A A N S K X Crude Oil Crude Bitumen Bituminous Coal Sub-bitumen Coal and Lignite Gold-Silver Nickel-Copper Copper-Zinc Lead-Zinc Iron Ore Molybdenum Uranium Potash Diamonds Timber Agricultural land 1961 to 2003 1967 to 2003 1975 to 2003 1975 to 2003 X X 1978 to 2003 1976 to 2003 1975 to 2003 1978 to 2003 1975 to 2003 1977 to 2003 1975 to 2003 1975 to 2003 1998 to 2003 1961 to 2003 1921 to 2003 X X X X X X X * X X * X X * A L B B C X X X X X X X Y U K N N W U T N X X X * * * * * * * * X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X P P P Legend: X indicates the availability of data. * indicates that the regional data are unavailable, but the national data are derived from these regions resources. P indicates partial--data are available since 2001. Table 3 shows that the availability of provincial and territorial data are even more restrictive than the national data in terms of commodity and time coverage. In some cases only one series is available for a region. For example, the natural capital index for Prince Edward Island (PEI) is essentially an agricultural land index. This is not because land is the only natural capital found in the province, but because there are currently no available data for the other types of natural capital in PEI such as timber. For the territories, agricultural land data are available only since 2001; therefore land is excluded for the territories. Similarly, timber data for Manitoba are also unavailable. Despite these limitations, the provincial index shown in appendix A would be useful in tracking the trend in resource stocks. The provinces and territories that have experienced significant improvements over the years are as follows: Saskatchewan mainly due to increase in the potash and uranium 21 reserves; Nova Scotia and Newfoundland primarily because of offshore oil and gas; and the Northwest Territories chiefly due to the addition of diamonds. On the other hand, the provinces that have experienced substantial declines over the years are the following: Manitoba and New Brunswick due to decrease in energy reserves, Ontario because of reduced mineral reserves, and Prince Edward Island due to shrinkage of agricultural land. The natural capital index for Alberta and British Columbia, and Quebec has slightly decreased over this period. The indexes show the overtime change of a region’s natural capital stock. Each region can use the respective index to formulate their strategies for conservation or regeneration. Although the index does not capture the inter-regional variation, it can be used to identify which regions are performing better than others over time. 7. Conclusion Although produced capital such as buildings and bridges are often considered substitutes of natural capital, there is a limit to substitutability as many of the ingredients of produced capitals are derived from natural capital. To construct a building, for example, in addition to human capital, natural capital such as rods and cements are essential. Thus, it is important to conserve, replace and regenerate natural capital for sustainable development. With the increase in incomes of the world’s populous economies such as India and China, the demand for, and hence the prices of resources are likely to go up. As a result, extraction as well as addition of natural resources may increase and the net change in quantity stock should be recorded to pursue sustainable development policies, which are important for a resource-based economy such as Canada. When resource prices go up, the value of the Canadian dollar as compared to the US dollar tends to go up. Following the 1997/98 East Asian financial crisis, commodity prices in the world market dropped and so did the Canadian dollar. In recent years, the resource prices as well as the value of the Canadian dollar have gone up. Resources that are viewed free today may become a scarce capital tomorrow. Also a resource that may not look feasible for extraction today may become a major source later. A decade ago, for instance, extraction of offshore oil and gas was not technologically and economically feasible. Today, however, offshore oil and gas has become a major source of Canada’s energy supply; in 2005, offshore oil accounted for 30% of conventional crude oil supply. Molybdenum, on the other hand, has started to disappear, with 80% depleted over the years. The disappearance and reappearance of resources or the addition of new resources creates a complication, if one wants to monitor the trend in the natural capital. This is because different resources are measured in different units. Also, in some cases, the stock data may not be available for monitoring as they are confidential at the regional level. In order to resolve both the comparability and confidentiality issues, this paper has proposed a 22 natural capital index based on well established theories of index numbers including the chain Fisher index—an ideal index number, which has been used in the Canadian System of National Accounts since 2001. Like other quantity indexes, the natural capital index is a weighted average of the physical quantity of the resources where the present value of expected rents is used as weights. Occasionally the weight can become zero, especially if the price drops significantly, then rent and thereby the PV become zero, which may distort the natural capital index. Also, the reserve data are subject to revision. Despite these limitations, the index seems useful and the best method to get an overall picture of the health of natural capital of a country or a region. From 1990 to 2005, Canada’s natural capital had fallen by 13%, which should be taken seriously. Much of this is attributed to the drop in minerals and timber, which plays a vital role in maintaining a stable climate and sustaining sound ecosystems. Certainly this drop in the natural capital stock is discouraging as Canada’s population has been growing. In 1990, Canada’s population was close to 27 million, and the figure increased to above 32 million in 2005--more than 13% growth for the period. Thus the per capita natural capital index has deteriorated further. These trends have highlighted the importance of conservation and regeneration of natural capital. To this end, the proposed natural capital index would be helpful, as it has enables us to pin down the source of depletion as well as addition. Also noteworthy is the marginal cost of producing the index would be very small, since the required data are already compiled by Statistics Canada for other purposes such as updating the national balance sheet. For conservation and regeneration, provincial and territorial authorities need to be involved since the provinces and territories are the owners and stewards of much of Canada’s natural capital. This paper has provided a picture of natural capital for these jurisdictions. Thus, policymakers as well as politicians may find the index useful for monitoring changes in resource stocks and developing appropriate sustainable development strategies for their jurisdictions. Finally, the index is expected to ignite further debate and discussion including the construction and signaling capacity of this new barometer. 23 Appendix A Natural Capital Index for the Provinces and Territories10 Figure 1A: Relative Share of Natural Capital and the NCI of British Columbia 120 100 Land 80 % 60 Timber 40 20 Mineral Energy 0 1978 1979 1980 1981 1982 1983 1984 1985 1986 1987 1988 1989 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 Year Energy Mineral Timber Land 120.00 100.00 80.00 % 60.00 40.00 20.00 0.00 1978 1979 1980 1981 1982 1983 1984 1985 1986 1987 1988 1989 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 Year Laspeyres_80_based 10 CL CP CF I am currently updating the (new time frame 1980-2003) provincial and territorial indexes, and the updated version will be ready soon. 24 Figure 2A: Relative Share of Natural Capital and the NCI of Alberta 120 100 Land Timber 80 % 60 Energy 40 20 0 1978 1979 1980 1981 1982 1983 1984 1985 1986 1987 1988 1989 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 Year Energy Timber Land 120.00 100.00 80.00 % 60.00 40.00 20.00 0.00 1978 1979 1980 1981 1982 1983 1984 1985 1986 1987 1988 1989 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 Year Laspeyeres_80_based Chained Laspeyres Chained Paasche Chained Fisher 25 Figure 3A: Relative Share of Natural Capital and the NCI of Saskatchewan 120 100 Land 80 Timber % 60 Minerals 40 20 Energy 0 1978 1979 1980 1981 1982 1983 1984 1985 1986 1987 1988 1989 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 Year 250.00 200.00 150.00 % 100.00 50.00 0.00 1978 1979 1980 1981 1982 1983 1984 1985 1986 1987 1988 1989 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 Year Laspeyres_80_based Chained Laspeyres Chained Paasche Chained Fisher 26 Figure 4A: Relative Share of Natural Capital and the NCI of Manitoba 120 100 % 80 Land 60 40 Energy 20 0 1978 1979 1980 1981 1982 1983 1984 1985 1986 1987 1988 1989 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 Year Energy Land 120.00 100.00 80.00 % 60.00 40.00 20.00 0.00 1978 1979 1980 1981 1982 1983 1984 1985 1986 1987 1988 1989 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 Year Laspeyres_80_based CL CP CF 27 Figure 5A: Relative Share of Natural Capital and the NCI of Ontario 120 100 Land % 80 60 Timber 40 Minerals 20 0 1978 1979 1980 1981 1982 1983 1984 1985 1986 1987 1988 1989 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 Year Energy Minerals Timber Land 120.00 100.00 80.00 % 60.00 40.00 20.00 0.00 1978 1979 1980 1981 1982 1983 1984 1985 1986 1987 1988 1989 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 Year Laspeyres_85_based Chained Laspeyres Chained Paasche Chained Fisher 28 Figure 4: Relative Share of Natural Capital and the NCI of Quebec 120 100 Land 80 % 60 Timber 40 20 0 1978 1979 1980 1981 1982 1983 1984 1985 1986 1987 1988 1989 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 Year Minerals Timber Land 120.00 100.00 60.00 40.00 20.00 Year Laspeyers_83_based Chained Laspeyers Chained Paasche Chained Fisher 20 02 20 01 19 99 20 00 19 98 19 97 19 96 19 94 19 95 19 93 19 92 19 91 19 89 19 90 19 88 19 87 19 86 19 84 19 85 19 83 19 82 19 81 19 80 19 79 0.00 19 78 % 80.00 29 Figure 5: Relative Share of Natural Capital and the NCI of New Brunswick 120 100 Land % 80 60 Timber 40 20 Energy 0 1978 1979 1980 1981 1982 1983 1984 1985 1986 1987 1988 1989 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 Year Energy Timber Land 120.00 100.00 80.00 % 60.00 40.00 20.00 0.00 1978 1979 1980 1981 1982 1983 1984 1985 1986 1987 1988 1989 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 Year Laspeyres_80_based Chained Laspeyres Chained Paasche Chained Fisher 30 Figure 8A: Relative Share of Natural Capital and the NCI of Nova Scotia 120 100 Land 80 % Timber 60 40 20 Energy 0 1978 1979 1980 1981 1982 1983 1984 1985 1986 1987 1988 1989 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 Year Energy Timber Land 600.00 500.00 400.00 % 300.00 200.00 100.00 0.00 1978 1979 1980 1981 1982 1983 1984 1985 1986 1987 1988 1989 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 Year Laspeyres_80_based Chained Laspeyres Chained Paasche Chained Fisher 31 Figure 9A: Relative Share of Natural Capital and the NCI of Newfoundland NFLD 120 100 Land % 80 60 Timber 40 20 0 Minerals Energy 1978 1979 1980 1981 1982 1983 1984 1985 1986 1987 1988 1989 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 Year Energy Minerals Timber Land 160.00 140.00 120.00 100.00 80.00 60.00 40.00 20.00 0.00 1978 1979 1980 1981 1982 1983 1984 1985 1986 1987 1988 1989 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 Laspeyres_2000_based Chained Laspeyres Chained Paasche Chained Fisher 32 Figure 10A: NCI of PEI—only land 102.00 100.00 98.00 96.00 94.00 % 92.00 90.00 88.00 86.00 84.00 82.00 80.00 1978 1979 1980 1981 1982 1983 1984 1985 1986 1987 1988 1989 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 Year Laspeyers_78_based Chained Laspeyers Chained Paaasche Chained Fisher Figure 11A: NCI of Territories—only gold 250.00 200.00 150.00 % 100.00 50.00 0.00 1978 1979 1980 1981 1982 1983 1984 1985 1986 1987 1988 1989 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 Year Laspeyres_80_based 33 Figure12A: NCI of the North West Territories—only diamonds 300.00 250.00 200.00 % 150.00 100.00 50.00 0.00 1998 1999 2000 2001 Year Laspeyres_98_based 2002 2003 2004 34 Appendix B The two ingredients of natural capital index are: 1) q--reserve or quantity data, and 2) V—present value data. 1. Reserve or Quantity Data Each year, various government departments such as Natural Resources Canada, Statistics Canada, and Alberta Energy Board gather production and reserve data by surveying the relevant businesses that are involved in exploration, drilling and extraction of the natural capital. Based on the survey results, the closing stock or reserve data of each of the resources are compiled. Agricultural land data are collected through the census of agriculture in every five years, and estimates are made for the intercensal periods. The survey also collects data on total revenue and extraction costs incurred by the establishment engaged in the production of the resource. Based on these data, the present value of the reserve of the resource is computed. The following formulas and hypothetical example can be used to understand the present value calculation process. 2. Rent and Present Value (PV) of Rent Rent, the value of a resource, is the difference between the value of current production and the extraction cost of the resource. ⎤ t ⎥ t =1 ⎣ (1 + r ) ⎦ RL ⎡ Rt PV = ∑ ⎢ where R = rent , r = discount rate t = current year , RL = reserve life = Stock Pr oduction Hypothetical example Suppose the established reserve of a mineral is 12 units, and each year 4 units are extracted. Then the reserve life would be 3 years. If the revenue generated from the extracted units are $20, and the extraction costs are $15, then the resource rent would be $5. Assuming that everything will remain the same for the next three years, the site will generate $5 worth of rent by the end of each year. However, $5 at the end of each year would worth less now, and therefore, all the future rents need to be discounted to derive the present value. Finally, by summing the discounted present value, the total PV of the resource can be calculated as shown in the following formula. Total PV = ∑ PV = 5 5 5 + + 1 2 (1 + .10) (1 + .10) (1 + .10)3 = $8.26 35 Appendix C Hypothetical Example of Calculating Quantity Index Number 0 A Q (kg) 3 1 2 Period QL = QP QF ∑q p ∑q p = = 1 0 0 0 ∑q p ∑q p 1 1 0 1 p ($/kg) 4 B q (meter) 1 p ($/meter) 8 5 2 7 2 * 4 + 2 * 8 24 = = 1.2 = 120% 3 * 4 + 1* 8 20 = = QL ×QP 2 * 5 + 2 * 7 24 = = 1.09 = 109% 3 * 5 + 1* 7 22 = 24 24 * = 114.42 % 20 22 Therefore, Q L (120%) f Q F (114.4%) f Q P (109%) In other words, the Laspeyers index is upward bias and the Paasche index is downward bias because the price and quantity relatives in the above example are negatively correlated. The opposite occurs if these two relatives are positively correlated. 36 Hypothetical Example--Chain Indexes Period 0 A Q (kg) 3 1 2 $/meter 8 2 5 2 7 1 6 3 6 ∑ qt pt ∑ qt pt ∑q p QL = ∑q p −1 QtL/ t −1 = −1 or $/kg 4 B q (meter) 1 −1 2 1 1 1 2 /1 ∑ qt pt ∑ qt pt ∑q p QL = ∑q p = 1 * 5 + 3 * 7 26 = = 1.08 2 * 5 + 2 * 7 24 = 1 * 6 + 3 * 6 24 = = 1.00 2 * 6 + 2 * 6 24 QtP/ t −1 = −1 or 2 2 1 2 2 /1 QtF/ t −1 = QCL × QCP Unchain Index Laspeyers Period 0 Unchain Paasche Chain Laspeyers % Chain Paasche % Chain Fisher % -- -- 1.00 = 100% 1.00 =100% 100 1.00*1.20 = 120% 1.00*1.09 =109% 114.42 1.20 1.09 1.08 1.00 1*1.20*1.08 = 130% 1.00*1.09*1.00 =109% 118.85 1 2 As stated in the methodology section, the chain Fisher index fulfills the criteria of an ideal index. Hence, the chained Fisher is used for the Natural Capital Index of Canada. 37 References: Allen, R.G.D. (1975), Index Numbers in Theory and Practice, Aldine Publishing Company, Chicago. Bartelmus, P. et al. (1991), “Integrated Environmental and Economic accounting: framework for SNA satellite system,” Review of Income and wealth, ser. 37, no. 2, pp. 111-148. Born, A. (1992), “Development of Natural Resource Accounts,” discussion paper number 11, EASD, Statistics Canada. Bortkiewicz, L. (1923), “Purpose and structure of price Index-number, First Article” Nordisk Statistics Tidscrift, 1.2, 369-408. Fisher, I. (1922), The Making of Index Numbers, Boston. Hotelling, H., (1931), “The Economics of Exhaustible Resources,” Journal of Political Economy, vol. 39, No. 2, pp. 137-175. Laspeyres, E. (1864), Hamburger Warenprecise 1850-1863’, Jahrbucher fur Nationalokonomie und Statistik, 3, 81 and 209. Paasche, H. (1874), Uber die Preisentwicklung der letzten Jahre,’ Jahrbucher fur Nationalokonomie und statistic, 23, 168. Statistics Canada, (1982), The Consumer Price Index reference paper, concepts and procedures, Ottawa. Statistics Canada, (1997), Econnections, Catalogue no. 16-505-GPE, Ottawa