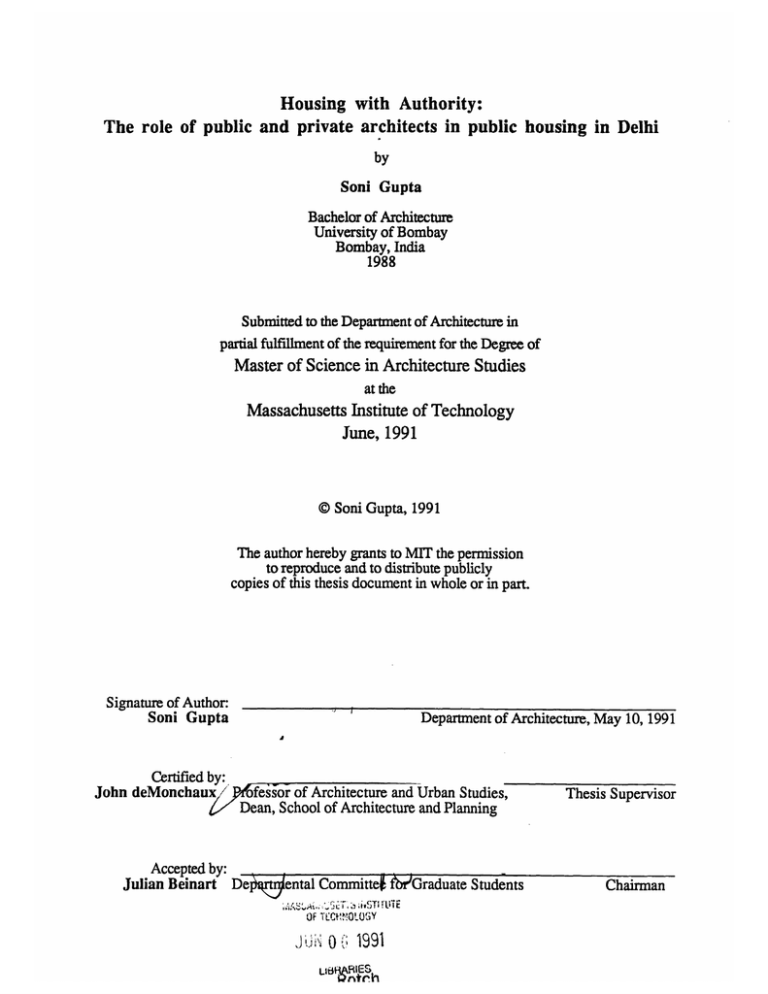

Housing with Authority:

advertisement