Document 10602096

advertisement

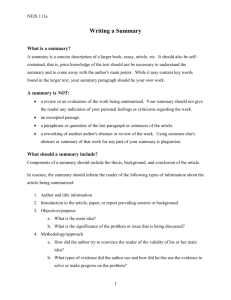

The Portable Editor Volume 6, No. 6 The one difference between a paper that can have a lasting impression on a reader and one that is forgettable often comes down to the time a writer spends editing for clarity and flow. That is, it takes effort to make a document reader-­‐friendly so the reader can concentrate on the message rather than the delivery vehicle. Those who take a moment to double or even triple check the finer details are more likely to find gaps that need filling or catch overlooked mistakes—problem areas that can cost even the best of writers a few points off a grade or possibly sink a grant proposal. In this latest issue, we offer some “best practices” for editing your own writing. After days of writing, take a break before you jump in to edit • • • Minimum of a 24-­‐hour break; ideally, at least 3 days to let your brain chill. In a pinch, an hour will do — try physical activity before returning to the grindstone. If you can’t wait 24 hours, try to fool your brain by altering the physical and visual aspects of the document. For example, changing the font type, line spacing, or margin settings can kick your brain off autopilot when you’re proofing or revising a paper. Run “no-­‐brainer” computer checks for last-­‐minute problems • • • • • Spell check Grammar check Check for overly long sentences. There’s no ideal word number, but sentences of more than 40 words are often better divided into simple, less complicated sentences. Check your list of “usual suspects” such as extra spaces and floating pronouns (e.g., it, these, this, they; any pronoun not anchored to its referent by a noun) Compare in-­‐text citations and reference entries. With the exception of personal communication, every in-­‐text citation must have a reference entry, and every reference entry must have a corresponding in-­‐text citation. Proofread! Print out a copy! • • • • • Read aloud; your mouth will trip over missing or repeated words that your brain will edit. First read-­‐through is for the big picture. Did you say what you wanted to say? Is your message clear? Look for overall flow—Are transitions between paragraphs smooth or bumpy? Examine content—Have you provided the reader with all the information needed? Have you “connected the dots” of your argument by clearly stating the relevance of the evidence to your point? Do you have unnecessary or extraneous details that could be cut? Do your sentences give information in the order needed to process each bit without backtracking? For example, do you give a list before telling the reader what connects the items in the list? Compare the following ways of presenting the same list: o Aggression, violence, and substance use are problem behaviors often exhibited in adulthood by those who were victims of bullying in childhood. (The reader doesn’t know how to process the list until reaching the end of the sentence, forcing most readers to go back and re-­‐read the sentence. Worse, many readers will just forge onward, missing important information.) o As adults, those who were victims of bullying during childhood often exhibit persistent problems behaviors such as aggression, violence, and substance use. • Do you present paragraphs in an organized and logical way? That is, does the paper present information so a reader without your depth of knowledge is able to understand your argument and follow your train of thought? Initial cleanup • • • • • • Should paragraphs be re-­‐ordered? Have you defined all technical terms? Have you defined all acronyms and abbreviations? Have you used the correct level headings? Have you used consistent spelling, capitalization, and hyphenation of names or labels? Have you checked format requirements? (margins, font, page numbers, length) • Read aloud line-­‐by-­‐line. Often, our ears will hear mistakes and catch clunky sentences before our eyes catch these problems. Correct grammar, spelling, and punctuation mistakes as you find them. Aim for concise expression. Cut bloated words that add length but not meaning. Consider word choices: Are you using words such as effect and affect accurately? Consider the subjective impact words have on the reader such as the difference between “allowed us to” (i.e., granted permission) and “enabled us to” (i.e., created a pathway). Can you substitute a short, direct word for an inflated word? For example, sub use for utilize or used for employed. Are your verbs conveying action or have you zapped the life out of your writing through nominalization (i.e., changing verbs to nouns)? For example, did you modify (verb) or report a modification (nominalization)? Did you collaborate with colleagues or join a collaboration? Concise writing is more powerful than lengthy prose that obscures the point. Second Read-­‐Through: Grab a Pencil! • • • • • • Bloated phrase Already existing Alternative choices At the present time Basic fundamentals Basic necessities Completely eliminate Very important Had done previously Currently underway Avoid Repetitively Redundant Phrases Concise choice Existing Alternatives Now Fundamentals Necessities Eliminate Important Previously Currently Bloated phrase Never before Period of time None at all Still persists Completely unique Past experience Existing research, Prior research Need One-­‐on-­‐One Writing Support? Please email to schedule an appointment: SOSWwritingsupport@gmail.com Concise choice Never Time (or period, but not both) None Persists Unique Experience Research + past tense (indicates the research has occurred)