MASSACHUSETTS: DEVELOPMENT Deborah L. Cantwell

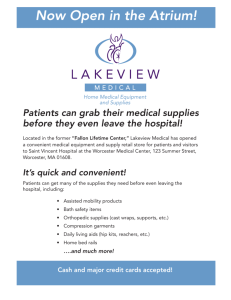

advertisement