Alternative Strategies for Public Transport Improvement

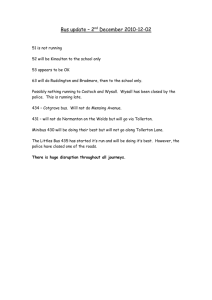

advertisement