THE DAIRY INDUSTRY IN KENYA: THE POST-LIBERALIZATION AGENDA By

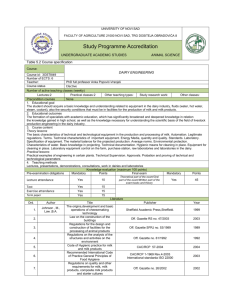

advertisement