Unit 5 Learning and Memory

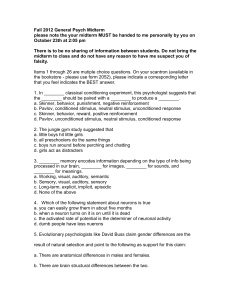

advertisement

Unit 5: Learning and Memory Chapters 8 and 9 Learning Nature’s most important gift to us is our adaptability We adapt through learning: a relatively permanent change in an organism’s behavior due to experience Philosophers John Locke, David Hume and Aristotle believed that we learn by association Associative learning: learning that certain events occur together. The events may be two stimuli (classical conditioning) or a response and its consequences (operant conditioning) Associative Learning Conditioning is the process of learning associations. There are two types: Classical conditioning: we learn to associate two stimuli and to anticipate events A flash of lightening signals an impending crack of thunder, so we learn to brace ourselves for thunder when we see lightening Operant conditioning: we learn to associate a response and its consequences and to repeat acts followed by rewards and avoid acts followed by punishment Pushing a vending machine button relates to the delivery of a candy bar We also use observational learning: learning from others’ experiences and examples Ivan Pavlov – Classical Conditioning Ivan Pavlov’s experiments explored classical conditioning and showed how scientific research can reveal learning principles that apply across species Pavlov’s study of how organisms react to stimuli in their environments influenced John B. Watson’s idea that human behavior, though biologically influenced, is mainly a bundle of conditioned responses Both Pavlov and Watson were behaviorists and believed that psychology should study behavior without reference to mental processes Pavlov’s Experiments - CC While doing experiments studying the salivary secretion in dogs, Pavlov noticed that dogs began salivating to stimuli associated with food (food dish, person who brings the food). Seen first as annoyances, Pavlov soon realized they pointed to an important form of learning. So, Pavlov and his assistants began different experiments: they paired various neutral stimuli, such as a tone, with food in the mouth to see if the dog would begin salivating to the neutral stimuli alone. From an adjacent room they would present food at a precise moment. If a neutral stimuli, a tone, regularly signaled the arrival of food, would the dog associate the two stimuli? If so, would the dog begin salivating to the neutral stimulus in the anticipation of the food? Pavlov’s Experiments - CC Results: after several pairings of tone and food, the dog began salivating to the tone alone Because salivation in response to food in the mouth was unlearned, Pavlov called it and unconditioned response (UCR) Food in the mouth automatically, unconditionally, triggers a dog’s salivary reflex. Thus, Pavlov called the food stimulus an unconditioned stimulus (UCS) Pavlov’s Experiments - CC Salivation in response to the tone was a learned response or conditioned response (CR) The previously irrelevant tone that now triggers the conditional salivation is the conditioned stimulus (CS) Remember: conditioned = learned; unconditioned = unlearned Pavlov’s Experiments - CC Pavlov’s Experiments - CC Pavlov’s simple demonstration of associative learning was so influential because the experiment identified five major conditioning processes: acquisition, extinction, spontaneous recovery, generalization, and discrimination Acquisition - CC Acquisition: the initial stage in classical conditioning; the phase associating a neutral stimulus with an unconditioned stimulus so that the neutral stimulus comes to elicit a conditioned response Timing: would conditioning occur if the UCS appeared before the CS? Not likely because classical conditioning is biologically adaptive and helps organisms prepare for good or bad events. Extinction and Spontaneous Recovery - CC Extinction: the diminishing of a conditioned response; occurs in classical conditioning when an unconditioned stimulus (UCS) does not follow a conditioned stimulus (CS) Pavlov sounded the tone again and again without presenting food; the dogs salivated less and less Spontaneous recovery: the reappearance, after a rest period, of an extinguished conditioned response (CS) Pavlov allowed several hours to elapse before sounding the tone again; the salivation to the tone would reappear Generalization - CC Generalization: the tendency, once a response has been conditioned, for stimuli similar to the conditioned stimulus to elicit similar responses Dogs conditioned to one tone also responded somewhat to the sound of a different tone never paired with food Generalization can be adaptive: children taught to fear moving cars in the street respond similarly to trucks and motorcycles Discrimination - CC Discrimination: the learned ability to distinguish between a conditioned stimulus and other stimuli that do not signal an unconditioned stimulus Pavlov’s dogs learned to respond to particular tones and not to other tones Discrimination has survival value: being approached by a pit bull may cause your heart to race, but it may not when you are confronted by a golden retriever Pavlov’s Legacy Classical conditioning is one way that virtually all organisms learn to adapt to their environment Pavlov showed us how learning processes can be studied; by isolating building blocks on complex behaviors Provided a basis for John B. Watson’s work Watson’s “Little Albert” Experiments - CC Watson presented 11 month old Albert with a white rat and, as he reached to touch it, struck a hammer against a steel bar just behind Albert’s head After 7 repetitions of seeing the rat and then hearing the frightening noise, Albert became terrified at just the sight of the rat Five days later, Albert showed generalization by reacting fearfully to a rabbit, dog, and sealskin coat, but not to vastly different objects like toys Operant Vs. Classical Conditioning The second type of associative learning, operant conditioning: a type of learning in which behavior is strengthened if followed by a reinforcer or diminished if followed by a punisher Both classical and operant conditioning involve acquisition, extinction, spontaneous recovery, generalization, and discrimination BUT classical conditioning involves respondent behavior: behavior that occurs as an automatic response to some stimulus And operant conditioning involves operant behavior: behavior that operates on the environment, producing consequences Operant Vs. Classical Conditioning Organism is learning associations between events that it doesn’t control: Classical conditioning Organism is learning associations between its behavior and resulting events: Operant conditioning B. F. Skinner’s Experiments - OC Centered on a simple fact of life that psychologist Edward L. Thorndike called the law of effect: rewarded behavior is likely to recur Skinner developed a ‘behavioral technology’ that revealed principles of behavior control Skinner Box - OC Working with rats, and later pigeons, Skinner designed an operant chamber (Skinner box): a chamber containing a bar or key that an animal can manipulate to obtain a food or water reinforce, with attached devices to record the animal’s rate of bar pressing or key pecking Skinner used shaping: reinforcers guide behavior toward closer and closer approximations of a desired goal Shaping Behavior - OC Using a method of successive approximations, scientists rewards responses that are ever-closer to the desired goal and ignore all other responses By doing this long enough, researchers can eventually shape complex behaviors Principles of Reinforcement - OC Reinforcer: in operant conditioning, any event that strengthens the behavior it follows; can be positive or negative Primary reinforcer: an innately satisfying stimulus, such as one that satisfies a biological need Ex: getting food when you’re hungry Conditional reinforcer / secondary reinforcer: a stimulus that gains its reinforcing power through its association with a primary reinforcer Ex: a rat in a Skinner box learns that a light reliably signals that food is coming; the rat will try to turn the light on Immediate and Delayed Reinforcers - OC Most laboratory animals only respond to immediate reinforcers, otherwise no learning occurs Humans, on the other hand, do respond to reinforcers that are greatly delayed (pay check at the end of the month, good grade at the end of the semester) A huge step in the process for humans to mature and have the most satisfying life, is to learn to delay our gratification for the benefit of long term goals Unfortunately, most of the time, small but immediate consequences are more alluring than big but delayed consequences Reinforcement Schedules - OC Continuous reinforcement: reinforcing the desired response every time it occurs Learning occurs rapidly, but so does extinction Partial (intermittent) reinforcement: reinforcing a response only part of the time; results in slower acquisition but greater resistance to extinction than does continuous reinforcement More applicable to real-life Reinforcement Schedules - OC Skinner and colleagues compared four schedules of partial reinforcement Fixed-ratio schedule: reinforces a response only after a specified number of responses Variable-ratio schedule: reinforces a response after an unpredictable number of responses Fixed-interval schedule: reinforces a response only after a specified time has elapsed Variable-interval schedule: reinforces a response at unpredictable time intervals Skinner found that the reinforcement principles of operant conditioning were universal; no matter what response, reinforcer, or species, the effect of a given schedule is the same Reinforcement Schedules - OC Punishment - OC Opposite of reinforcement is punishment: an event that decreases the behavior that it follows Although punishment can be successful in suppressing a behavior, some psychologist believe it may lead to undesired responses of anger, fear, or resistance Since punishment only tells you what not to do, punishment combined with reinforcement is usually more effective than punishment alone Latent Learning – OC Although Skinner did not believe that cognitive processes have a place in psychology, evidence of cognition has come from studying rats in mazes While exploring a maze with no obvious reward, the rats seem to develop a cognitive map: a mental representation of the layout of one’s environment, of the maze Latent Learning - OC Then, when a reward is placed in the maze’s goal box, the rats perform as well as rats that have been reinforced with food for running the maze During their explorations, the rats seemingly experience latent learning: learning that occurs but is not apparent until there is an incentive to demonstrate it Learning can occur without reinforcement or punishment, and there is cognition Overjustification - OC The power of rewards can sometimes be detrimental Overjustification effect: the effect of promising a reward for doing what one already likes to do; the person may now see the reward, rather than the intrinsic interest, as the motivation for performing the task Overjustification with excessive rewards can undermine intrinsic motivation: the desire to perform a behavior for its own sake and to be effective Extrinsic motivation: a desire to perform a behavior due to promised rewards or threats of punishment A person’s natural interest usually survives when a reward is used neither to bribe not to control, but to signal a job well done Biological Predispositions In both Operant and Classical Conditioning, learning can only occur to the extent of the species’ biological predispositions Pigeons can easily learn to flap their wings to avoid being shocked and to peck to obtain food, but they have a hard time learning to peck in order to avoid a shock or to flap their wings and eat with their beaks Biological constraints predispose organisms to learn associations that are naturally adaptive Observational Learning Among higher animals, especially humans, learning need not occur through direct experience The process of observing and imitating a specific behavior is called modeling Social behaviors such as our catch-phrases, ceremonies, foods, traditions, and fads all spread by one person copying another Observational Learning Recently, neuroscientists have discovered mirror neurons: frontal lobe neurons that fire when performing certain actions or when observing another doing so The brain’s mirroring of another’s action may enable imitation, language learning, and empathy The imitation of models shapes a child’s development Shortly after birth – an infant may imitate an adult who sticks out his tongue 9 months – infants will imitate novel play behaviors 14 months – infants will imitate acts modeled on tv Albert Bandura’s Experiments A preschool child is coloring in a room when he sees an adult on the other side of the room get up and kick, pound, and throw a large inflated Bobo doll around the room After observing this outburst, the child is taken to another room with appealing toys and then told these good toys were for other children Then, the frustrated child is taken to another room with a few toys, including a Bobo doll Those who observed the adult’s outburst, when compared to those who did not, were more likely to lash out at the doll Bandura’s Bobo Doll Experiment Observational Learning What determines whether we will imitate a model? Reinforcements and punishments We watch to learn and anticipate a behavior’s consequences in situations like those we are observing Antisocial behavior such as family abuse can be passed on to younger generations who regularly observe violence in the home On the other hand, prosocial behavior: positive, constructive, helpful behavior; can prompt similar behavior in others Ex: Mahatma Gandhi and Martin Luther King Jr. Models are most effective when their actions and words are consistent Television and Observational Learning Does viewing more violent programs on TV lead to people committing more violent crimes? Although those who watch more TV are more likely to commit crimes, correlation does not imply causation; maybe aggressive children prefer violent programs. However, prolonged exposure to violence can desensitize viewers. Memory Memory: the persistence of learning over time through the storage and retrieval of information Studying memory’s extremes has helped researchers understand how memory works Your memory capacity is perhaps most apparent in your recall of flashbulb memories: clear memories of an emotionally significant moment or event Ex: most people can recall where they were when they heard the news of 9/11 Information Processing Our memory is in some ways like a computer system’s information processing system To remember any event requires that we get information into our brain (encoding), retain that information (storage), and later get it back out (retrieval) Our memories are less literal and more fragile than a computer’s Atkinson-Shiffrin’s Three Stage Processing Model of Memory According to Richard Atkinson and Richard Shiffrin, we first record to-beremembered info as a fleeting sensory memory, from which it is processed into a short-term memory bin, where we encode it for long-term memory and later retrieval 1. Sensory memory: the immediate, initial recording of sensory information in the memory system 2. Short-term memory: activated memory that holds a few items briefly before the information is stored or forgotten 3. Long-term memory: the relatively permanent and limitless storehouse of the memory system However, this process is limited and fallible Working Memory The newer concept of working memory clarifies the short-term memory concept by focusing more on how we attend to, rehearse, and manipulate information in temporary storage Working memory integrates information coming in with that retrieved from longterm storage Includes a visual and a verbal component Encoding Automatic processing: unconscious encoding of incidental information, such as space, time, and frequency, and of well-learned information, such as word meanings; difficult to shut off Effortful processing: encoding that requires attention and conscious effort We can boost our memory through rehearsal: the conscious repetition of information, either to maintain it in consciousness or to encode it for storage