Why Flexion Isn't the Devil

advertisement

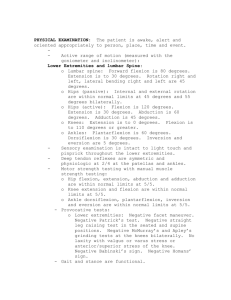

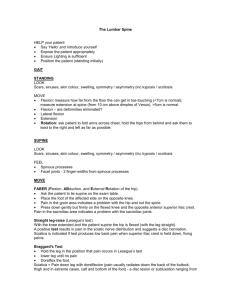

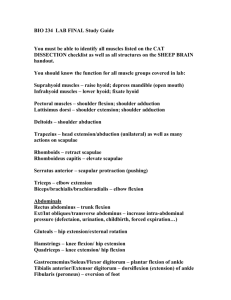

Last week, I got an email from a personal trainer saying that he really liked my Maximum Strength training program, but that he'd have left out the reverse crunches if it was his program because he "doesn't use any lumbar flexion work" in his programs anymore. The book was published in 2008, so I gather that he is under the assumption that I should have jumped on board the anti-flexion bandwagon that's been amassing members over the past 3-4 years. That perception certainly has backing in the scientific world: if you want to herniate a disc, go through repeated flexion and extension at end range. If you want to see a population of folks with disc herniations, just look at people who sit in flexion all day; it's a slam dunk. And, you certainly don't want to go into lumbar flexion under compressive loading. As far back as 1985, Cappozzo et al. demonstrated that lumbar flexion during squatting increased compressive loading on the spine. These points in mind, I'm a firm believer that you should avoid: a) end-range lumbar flexion b) lumbar flexion exercises in those who already spend their entire lives in flexion c) lumbar flexion under load It seems pretty cut and dry, right? Don't move your lumbar spine and you'll be fine, right? Tell that to someone who lives in lumbar hyperextension and anterior pelvic tilt. Let me make that clearer: Flexion from an extended position to "neutral" is different than flexion from "neutral" to end-range lumbar flexion. In the former example, we're just taking someone from 20 yards behind the starting line up to the actual starting line. In the latter example, we're taking someone from the starting line, through the finish line, and then violently through the line of people at the snack shack 50 yards past the finish line as nachos and Italian ice fly everywhere and the spectators scurry for cover. You get a gold star if you take out the band, too. If you're someone who trains predominantly middle-aged to older adult clients, by all means, nix flexion drills. However, I deal with loads of athletes - most of whom live in lumbar extension and anterior pelvic tilt. Now, I'll never be a guy who has guys doing sit-ups or crunches, as they can shorten the rectus abdominus, thereby pulling the rib cage down when we're working hard to improve thoracic extension and rotation. Additionally, most athletes absolutely crank on the neck with these - and that leads to a host of other problems. For reasons I outlined in a recent post, Hip Pain in Athletes: The Origin of Femoroacetabular Impingement, we need to work to address anterior pelvic tilt and excessive lumbar extension - which can lead to a "pot belly" look even in athletes who are quite lean. Enter the reverse crunch, which selectively targets the external obliques over the rectus abdominus. As Shirley Sahrmann wrote inDiagnosis and Treatment of Movement Impairment Syndromes, "The origin of this muscle from the rib cage and its insertion into the pelvis are consistent with the most effective action of this muscle, that is, the posterior tilt of the pelvis." We utilize reverse crunches as part of a comprehensive anterior core strengthening program that also includes progresses from prone bridging variations to rollout variations and TRX anterior core work (as well as anti-rotation exercises to improve rotary stability). And, I can say without hesitate that this addition was of tremendous value to an approach that got cranky baseball hips and spine healthier faster than ever before at Cressey Performance. In summary, remember that flexion isn't the devil in a population that lives in extension. Contraindicate the person, not the exercise. To learn more about our comprehensive approach to core stabilization, be sure to check out Functional Stability Training of the Core.