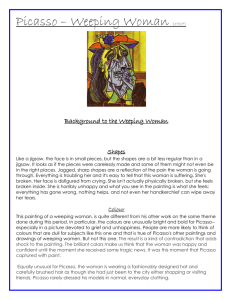

here

advertisement

DORA AND THE MINOTAUR – My Life With Picasso A novel "Art is a lie that helps us understand the truth." Pablo Picasso (pp. 1-12) Introduction The famous French surrealist photographer and painter Dora Maar, or Henrietta Theodore Markovitch as is her real name, died in 1997. Among numerous papers, documents and notebooks written in French, a notebook in Croatian was also found in her apartment in Rue de Savoie 6 in Paris. Croatian was the language of her father, Joseph Markovitch (Sisak 1874 - Paris 1973). She spoke it fluently, but rarely used it except when she met her father once a week - as opposed to French, the language of her mother Louise Julie Voisin (Cognac, 1877 – Paris, 1942), which she spoke every day. It is quite possible these notes held particular value for her, and the Croatian language was a connection to her emotional life, which in her case was associated with her father, and not her mother. In addition to being a photographer, Dora Maar is also known as the muse inspiring Pablo Picasso (Malaga 1881 – Mougins 1973). As can be expected, her life with Picasso, their separation and traumatic consequences for Dora were a focal point of her notes. But the main topic was her experience of the relationship of the two creative personalities, one being exceptionally dominant. In that sense, it felt appropriate to call this book Dora and the Minotaur, after Picasso's famous and symbolic drawing from Mougins, dated September 5th 1936. Some sources claim that it was around 1958 that she started writing undated notes , inspired by her meetings with Dr. Jacques Lacan, marked in her diary with the letter A for analysis. They are neatly written by hand, in purple ink. That was when Dora Maar decided to withdraw from public life, living in solitude until her death. This rather short manuscript gives an impression of an outline for a future autobiography, which the artist evidently later gave up on. The notebook - and this might well be the "Menerbes notebook" mentioned by Dora's biographers - was sold in 1999 at an auction entitled Dora Maar's Last Memories. After the death of its anonymous owner, it traced an obscure path to her father's homeland. Regardless of the fact that this is a fragmented and actually unfinished text, as she herself notes in the 1973 post scriptum, it provides invaluable insight into the creative personalities of both Dora Maar and Pablo Picasso and deserves to be published. S.D. Recently, while looking for a magazine, I found an old notebook among the papers . I thought it was empty, but on the first page I found a note from June of 1945: I left Jacques in such high spirits yesterday! I felt much better. Lying in the hospital for a long time after electroshock therapy I still felt as though my legs were made of wood. Every part of my body ached for days. I ambled around my own apartment almost unaware I was back home. The green color of the bushes mixed with the white and grey of the inner courtyard made me feel as though I were swimming in murky waters. My brain was recovering very slowly. Jacques barely managed to pull me out of Sainte Anne Hospital where they almost killed me: they tied me to the bed, put a wad of cloth into my mouth and then passed a current through my body. I don't even know how many times... Fashion, said Jacques during our first meeting after I left the hospital, simple fashion - in that, medicine is just like hats or shoes. But I can still barely feel my body! Forget it, it will pass, you're not even forty. You will come to see me and we will talk. Nothing else. You don't need any medication, you no longer need to be afraid. I don't want to go back there. You don't have to. You are the one who decides now. Tell me what you want to talk about. No, you tell me how I ended up in the hospital? And here with you? Did I have a nervous breakdown? Was Picasso worried about my mental health? Mind you, only someone who doesn't know him can think that. I think he simply had me put into an insane asylum to get rid of me. Ok then, tell me what those who know him think. I waved my hand indistinctly. In his cabinet, the afternoon sun gently lit up the bookshelves, the massive walnut table, his skinny figure with protruding ears in a navy blue blazer. It smelled of books and tobacco. On the way home I went to a stationary shop. I bought, a black, lined notebook. I hated lines in school because I was very neat and my letters never slid below or above them. But now, with my head as fuzzy as it is, it would be difficult to write properly. I also bought a bottle of purple ink. Putting the notebook away in my bag, I thought I could try to put some thoughts on the paper. I don't need to show it to anyone, after all. Not even Jacques. I also decided to write the notes in Croatian, so that no one but me would be able to read them. I saw this as an attempt to reclaim myself. If I recall some events from my past, if I write them down, perhaps I would be able to understand what happened to me? In fact, this is the same procedure as in my work. When I take photographs or paint, I choose who I will capture and how. I control the reality and shape it. I decide. You are the one who decides, isn't that how he put it? Those words made me feel empowered, but not for long. When was it that I actually decided something? Except when I took photographs, which I haven't done for years. I can barely remember the feeling. Was it a decision to pick up photography – or just intuition? Did I actually choose to no longer take them? Is everything that happened in between a result of other people's decisions? By the time I came home from Jacques's, the idea of writing notes seemed problematic. And that was all. Those words written many years ago touched me. Suddenly I was unsettled by the empty pages that followed. Why didn't I continue writing? What scared me off? What disturbed me? I could clearly see the young doctor at the beginning of his psychoanalytical practice, the stationary shop window and my reflection in it. I remembered feeling I was not lost, that I was not completely abandoned. Now my hands - those same hands Picasso painted so many times - hold this notebook with a few words written long ago. This is a testimony to my own insecurity. What I didn't put down then, I will put down now. Because Jacques was wrong about one thing. Almost a decade after being treated by him, I am finally in a situation to decide for myself. I still remember some conversations with Jacques. And how his questions seemed to open hidden doors, inviting torrents of memories I will try to capture here. I should have that purple ink somewhere in here... Dora, tell me what you see when you close your eyes? Curtains. I see white curtains fluttering in the breeze. The curtains are on the glass doors of my room in Buenos Aires. Only the door separates mine from my parents' room. It is this image that keeps coming back to me these days - the glass door of my childhood. The moment I close my eyes I am in Buenos Aires. I am four, perhaps five years old and lying in my bed. I see thin white curtains on the door, the only thing separating me from my parents. In the morning, I can just make out the outline of their bed and hear my father's muffled, threatening voice. I am familiar with that special voice of his which he uses only with maman, and only since we have moved here. Afterwards, maman tells me father had another "attack". She calls it l’attaque, as though he were a lunatic, and not just a choleric man whose wife's frowning face is spoiling his day right from the very morning. I sense, I can feel it in his voice, father would love to yell at that sniveling woman next to him. But he can't because of me. That's why the higher tones are acquiring a hissing quality, as though he transformed into a large loud snake strangling and squeezing her, leaving her lungs with just enough air to allow her to cry quietly. Of course, I shouldn't have heard their fights. But I was sleeping in the room separated by sliding doors, a flimsy veil blurring the image, but hardly the sound. He talks to her in French, but I also understand his language, Croatian. To my child's ears it sounds sweet, warm, silky: Draga moja Dorice, my father coos at me and I bask in his tenderness. Until he bends down to place a kiss on my cheek. His kiss is wet and the touch of his lips makes me shudder. I shouldn't hear other sounds either. In the middle of the night, I remember being awoken by mamans' sighs. Quiet at first, then louder. Her voice turns into a moan. I am afraid that she might start crying and I'm about to get up and open the glass door. I am sitting up already, looking in the dark for my slippers which have slid somewhere under my bed. I get down on my knees. The floor is wooden and squeaky. I feel around with my hands. Why am I even looking for my slippers? It is summer, and the wooden floors are pleasant to the touch. Right before I gave up and decided to go bare-footed, suddenly there is silence. I slowly crawl back into bed. They must have heard me. Once, when the same thing happened I did open the door, concerned. I saw father above her. His silhouette, outlined against the window. It seemed threatening, all black and bent over her. Was he strangling her? Maman was making weak noises, something between a whine and a sigh. Daddy, I whispered, is maman all right? Dad straightened up in bed. Dorica, dobro je, go back to bed. Maman just had a bad dream, but she's all right now. I believed him, even though she made frightening noises - sighs, groans, muffled cries. Father consoled me. He was probably surprised I was awake. My parents were unaware that I could also see them, that circumstances were forcing me to listen to them, that I knew more about them than they'd like. In their eyes I was only a child. They didn't think that this child was growing up and starting to understand their coded language in which hatred and indifference were taking turns. I wonder why they gave me that room? I was an only child, but was I really a tender shoot that needed to be placed in a greenhouse and watched over day and night? Why did they take the living room, which could be made larger by opening the glass partition, and make it into two bedrooms instead? Why did they turn the bedroom into the living room? I believe they decided to do this out of concern for me and that this was one of the rare decisions they made together. Maman was 30 years old when she had me, she had already lost hope of having a child. Anyone who cared to listen would hear her story how in the delivery room the midwife scolded her for waiting so long to have a first child. And my father at thirty-three was also no longer considered young. Their marriage had no chance without a child. But with me, at least a certain framework was imposed on them. Obligations, sad obligations, as I soon came to understand. A soon as I was born, all of father's tenderness was transferred from my mother to me, and maman was given the status of my keeper while he was at work. Julie, how is Dorica, were his first words as he'd come home in the evening. At night they could hear me breathing peacefully and calmly fall asleep themselves. In the morning, usually my father would first pull aside the curtain and take a peek to see if I'm awake. If I opened my eyes, a smile would light up his face and he would cover in kisses my sweaty dark locks. If I pretended to sleep, especially when he had l’attaque, he would just pat me on the head. He never left the house before seeing daddy's little girl first. I remember, after his attack maman remained in bed for a long time, happy I was not bothering her. She was angry at father because early in the morning he already hissed at her in his threatening voice. If only he would yell at her like a real man! But also because of his work that forced them to move from Paris to Buenos Aires, right among the savages. What a horrible city, she would say. Everything in that city was insulting - the roads, the dirt, immigrant sex-starved workmen who stared at women, the market where the villagers spread their fares on the ground, the women in their dresses from the previous century. God, how unsophisticated everything was, so primitive, maman would say to Mrs. Dupont, with whom she associated only because she was French. She imagined that being French in Buenos Aires at that time was very elegant, but soon she found out that was not exactly the case. The only reason she agreed to move was father's work and his words: people come to Argentina to get rich, he would say. Yes, father knew how to be charming and convincing when he wanted to, she had to give him that. But as time passed and there was no sign of the promised wealth, her discontent grew, as well as her daily reproaches to father. I was forced to overhear all of that, as well as her sighs and crying. And increasingly more rare, the squeaking of their bed at night. I remember the feeling of being exposed to watchful eyes. The feeling I was in a shop window or an aquarium. Because I am once again naked. Unprotected. And I lost my camera for good. My hands are empty now. When father would leave, I would feel his eyes on me for a long time still. I knew if I didn't get up, maman would also get up at some point to check if I am alive and breathing. Her gaze was different. It had no spark of warmth and expectation, not like father's smile and kiss as he's leaving, as though he were leaving forever. I knew maman had better things to do than to dedicate her early morning hours to me. For the next hour she would close herself in the bathroom and use cold presses to alleviate the signs of crying, while I was left to my own devices and free of control. I didn't like that room because it was not exclusively mine. As I grew older, it made me feel more and more naked. Finally I only got changed in the bathroom. I remember well that feeling of being protected and exposed at the same time, that glass cage I couldn't leave or hide in, but only inhabit. And because of this room, I already felt discomfort as a child. Much later I recognized this discomfort at being exposed to unwanted glances, which I eased by hiding behind the lens of my beloved camera. The camera became a shield which gave me the opportunity to withdraw, to hide. But also a means to communicate according to my own rules. My magical camera through which I tamed everything in front of it. I defended myself by playing: I am seven or eight years old and like to play with light. The glass door to my room is open and rays of light are making their way to my bed through the large window facing the street. I love to be alone, unwatched. I open and close my eyes and a bright red colour under my eyelids interchanges with blinding light of the sun rays. I lift my hand towards the window. Bright light penetrates my skin and I see darker parts and a thin network of veins. Are those dark lines bones, I wonder. My hand looks like something else, not a hand, like a transparent little animal, perhaps a jellyfish I once saw. In any case, something foreign, separate from me. And then I put that something away in the dark under the sheet, and it once again becomes my hand. I look at it in disbelief. The metamorphosis of my own body parts fascinates me. Things, depending on light and shadow, can turn into something else. I am a magician, I tell maman later, I turn things into other things, here, look! I didn't know the word artist at the time. Such words did not inhabit our world. Maman tells me to stop talking nonsense, she doesn't see the magic even when I show her how easily I transform a hand into a jellyfish using the light. And she says a hand is not a thing. I can see she doesn't understand light or my passion for the game of pretend. But that doesn't make me sad, because I have something completely my own, my secret. Maman takes me to the playground where I can play with girls who speak only Spanish, the language of servants, sailors, porters and farm hands, a useful but dirty language, like the dirty people around us. I felt divided. As though I were made of clean and dirty parts. I always felt that way. Now too. Theodora, Dora, Dorica, Dorita, Adora are all contained within me. **** (pp. 47-50) That July evening in our room, he approached me from the back and held me tight by the waist. He had strong hands, rough palms, tanned skin. He easily lifted me, threw me on the bed and fell onto me. Through an open window I heard Paul's voice on the terrace and Nusch's laughter. The room was still warm from the afternoon sun and through half-closed eyes I saw his face above me and felt his weight, his strength. At the beginning of our relationship, I liked his roughness and I gave in to it gladly. The way he would approach me suddenly, grab me, no questions asked, as though I were his property. Afterwards his voice startled me from sleep. Dora, I will show you what I drew this afternoon! He turned the light on and all of a sudden, a rather small drawing of a woman and a man with a bull's head was in front of me. That's you and me, see? Dora and the Minotaur he said with boyish pride, pointing his finger at the paper and waiting for my reaction. The drawing is brutal. I hate it. I adore it. From a red background a woman's body emerges, spread in an unnatural position. It is prostrated below a threatening black male body with an enormous bull's head. The bull is pushing her legs apart, spreading them further in hope of exposing her genitalia completely, while reaching for her breasts with the other hand. The woman is not resisting, but she is also not looking at him. She is passive. Her elegant arm with a bracelet and manicured fingernails is in the foreground. Her weak gesture does not make it clear whether she is trying to protect herself by moving his hand away or if that's merely a pose. It's obvious she can't do anything but give in to the strong animal, but it remains unclear if it is about to tear her apart, bite or rape her. It's like he is telling her, I'm going to show you, you'll feel my power. You cannot seduce me without paying the price, he's telling her. I am your master. I will tame you! Thite body is not showing tension but yielding. She is spread under him like a rug. I don't know how long I stared at the drawing. I didn't say anything. Picasso left the room like a disappointed boy and joined Paul and Nusch on the hotel terrace. I hate the dark red color he used to paint the background, I hate it to this day. And how it blends into orange and yellow. That drawing does not need color, especially the color of blood. The entire scene is bloody and would be so even if it had remained black and white. But Picasso couldn't resist the drama. The power of the black bull and the spread whiteness of the woman weren't enough for him; he had to have recourse to the red, underlining his intention to sacrifice her. Obviously the scene is taking place in the arena or the theatre. There is nothing intimate in the act about to take place. Quite the contrary, the Minotaur needs an audience, eyes, many eyes. He yearns to demonstrate his power in front of others, for their approval, their cheers. Bravo, you're the best! Show her, go on! I can almost hear the cries of the multitude, the cheering, their excitement growing. When Picasso left the room, I covered my head with a pillow and sunk into the darkness, into silence. I had nowhere else to run. The worst of it is, I didn't even want to. Even though the threat was only announced, I could clearly feel it in my body. But after all, I was on the drawing, I and no one else. Not Olga, or Marie-Terese. I was the chosen one, the winner, marked. His. It turned out not to be just a drawing, but a sign. Our entire future relationship was contained in it - my tamed gaze and his strong body leaning over mine. Invisible eyes pointed at us. Domination, submission - all that was about to come true in the seven years spent together. Part of him already knew what would happen to me while he was drawing, the part that made him an ingenious painter. You see, Picasso knew himself. I experienced that picture very emotionally and that was good, because a picture should make us react directly. But my experience was personal at the same time, the picture was not only intended for me, but I was on the picture. On one level I was proud, vain as I was. But when I look at it now, when I think about it more than twenty years after it was created, I know exactly what I responded to. There was something so negative, something that disturbed me so much - it's not the overall threatening, dark, violent tone of the picture, but my face which doesn't show fear. It should've shown fear, terror in fact. Some other painter wouldn't have resisted simple emotions and would've painted just that: a powerless, defenseless woman giving in, but with resistance reflected at least on her face. The problem is that Dora on that picture is calm, looking somewhere above the Minotaur, as though she might be anticipating pleasure. Isn't that a clear indication of their perverse relationship? That face confuses me to this day, because it was drawn with the exact intent of suggesting various possible experiences to the viewers, including the hint of masochism. But I am only able to think that way when I manage not to see the woman on the picture as myself. When I look at it with the awareness that the face is mine, I know (only now, of course) that Picasso, at the time he was creating that drawing, still saw me as Bataille's former lover. That fact challenged him, both as an artist and as a man. But the challenge also lies in the fact that the woman in the submissive position is still arrogant. And a man must dominate an arrogant woman, she must bare the pain and the excitement the pain brings. Her only defence is her equanimity, self control which maddens the Minotaur and enrages him further, making him desire revenge. There is one more thing I feel when I look at that picture today... Minotaur's wild sexual desire which, because he is half beast, is not connected to the woman. Despite my face, the woman under the bull is not me, but any woman. **** (pp. 120-125) I remember that James and I once visited Jacques and Sylvie in their house with a large garden in Guitrancourt. I don't know why I brought him with me, perhaps to see up close my then former doctor with his eccentric taste and strange behavior. And as though he wanted to confirm my description, he had yellow shoes on and a colorful vest in which he looked like a parrot. At dinner he read a book and smoked a cigar, ignoring the guests. James, like other visitors, was flabbergasted at the difference between Dr. Lacan's image of a provincial dandy and what he actually was. Jacques was aware of the impression he would leave so he used to make jokes at his own expense: given my profession people probably expect me to be dressed like a priest, he would say. After dinner, as though he wanted to improve the impression, Jacques invited us to his studio. I had an inkling as to why. It was not the first time I was witness to that ceremony of shocking the visitors who suspect nothing and are honored by the invitation. On one wall in a heavy golden frame there is an abstract erotic drawing by Andre Masson - Sylvie's sister's husband. But that drawing is only a cover, an appropriate decoration hiding something else. Literally so, because once you lift it, Gustave Courbet's The Origin of the World appears underneath. While he uncovers it, Jacques anticipates our reaction, and I can already see the spark in his eyes. He reminds me of a boy who keeps a pornographic magazine under his textbook and when the teacher goes away, takes it out and shows it to the others. The painting called The Origin of the World is a female nude, with realistically painted genitals in the foreground. Was Jacques showing this painting to his male visitors with a specific intent - to fascinate them, perhaps entice them? Or was this his way of demonstrating power, because it was scandalous in itself to own that provocative painting, that was rumoured to have disappeared. It was deemed insulting to the public sense of morality, which instantly turned it into a status symbol. Jacques bought it recently, at an auction for a lot of money and I believe the new acquisition was the main reason he was showing it. It was previously owned by the Ottoman ambassador, commissioned in 1866 for his collection of erotica. Jacques didn't comment the picture in front of us, he carefully observed our reactions. James was fascinated enough to make Jacques happy. Satisfied with his reaction, he closed his "magic box" and left. We were left with the more abstract drawing by Andre Masson. On the way home, James and I fell into silence. The picture impressed him - but I was certain he saw it differently than I did. In fact, this was the first time my thoughts remained on the picture whose dramatic unveiling I had already witnessed. Perhaps because at that moment, under the influence of a new element in my relationship with James, I was more aware of my femininity. Courbet painted The Origin of the World for a male audience. He painted female genitalia the way men see it, because women, unlike men, do not see theirs. What we don't see doesn't affect us the same way. It's paradoxical, but Courbet's view of the female is foreign to women, According to that logic, when women see that painting, shouldn't they have a stronger reaction than men? So for me, there is a female eye and a male eye. But what does a man see on that painting? He sees exposed genitalia which, from a slightly greater distance, seems like a black furry animal nesting comfortably between a woman's legs. From up close it's a tuff of hair that looks messy, perhaps even repulsive. A male eye sees an entrance which is at the same time an exit. A female body that can be entered by a man but it also gave birth to him. And that realization shocks him perhaps even more than it excites him. Yet, the most important thing, the point of exit, is also the place where he could get lost, that could swallow him up. But it is still a place in which pleasure is hidden, a secret dark place of longing and fear which remains hidden from his sight. On Courbet's painting a grown man sees what he already saw many times. The surprise does not consist of discovering an unfamiliar sight. I wouldn't even say the erotic element prevails, despite the objections regarding the public morality. Courbet's painting, precisely because of the way it was painted, is not only erotica. And this is precisely why it directs the viewer to its meaning. All of a sudden, the viewer realizes The Origin of the World is not a naive or ironic title. Faced with that painting, it's difficult not to have women's power come to mind, the fact that their bodies give both pleasure and life, that a woman is both their lover and their mother, that they came to existence through that body. That insight must in some way be frightening. If I were a man, I would think: subjugate, conquer, control. And all of a sudden, I see that painting from the Minotaur's position, forcing the white woman's legs apart, to see that same thing between her legs. Courbet painted The Origin of the World. Picasso drew Dora and the Minotaur. Both works talk about the same thing in different ways. Courbet exposes the woman in a way hinting at her hidden power. Picasso draws primal fear of women that men feel when looking at Courbet's painting. His Minotaur responds to fear with violence. It's only looking at Courbet's painting that I understand why. --Looking through my camera I turned into an eye, believing this way I would avoid being looked at, but I still couldn't avoid this, the thing I came to call "Courbet's gaze". What I was afraid of is exactly what happened. It's not true, as Picasso says, that a woman is not a woman if she's not a mother. No, a woman is not a woman if she is not francesa, a whore: the male eye is always on you, it follows you with a certain gaze. Regardless of your attempts to exit the female role through art or literature, it imprisons you in your body. While such a gaze follows you, you're nothing but a francesa. But you comprehend that when you want to stop being only that: even when you deserve respect for your work, when you run away from prejudice – that gaze reduces you to "the origin of the world." If Jacques had only, while I still went to analysis, taken me seriously as an artist and carefully looked at my photographs. At that time he probably also couldn't see beyond the given framework that puts, like Courbet, the gender in the foreground. My problem was that I wanted to be special, or specially attractive, unusual, mysterious like a francesa - and at the same time to be an artist free of Courbet's gaze. I don't know why he didn't support my return to my true profession, he obviously felt I wasn't strong enough for it. But I believe, had Jacques bothered to look at them, he could have learned more about me. I don't think listening to me was enough to understand me. My words are not enough for that. I know, because after twenty years I had to get back to my photographs to become fully aware of them, in order to understand myself better. At the time, I was just taking photographs, unaware of their many meanings. I trusted my subconscious. My erotic photographs from the period were a transgression, which Bataille understood best because he did the same thing in his writing. And that attracted him to me: he was more aware of my work than I was. Looking at me, he was really looking for the photographer who took them. It didn't take him long to conclude that I could commit transgressions only in art, not in life. And yet, he knew - as I also now know - there was something in me that made my strange disturbing photographs possible. I am looking at my 1935 photo called Forbidden Games. I see everything in it: my entire life, my parents, my lovers, myself looking at the scene. I see my own voyeurism which attracted Bataille and Picasso. If Jacques had taken a closer look, he could have seen the eye he later wrote so much about. It is a photomontage showing a plain bourgeois salon, very much like mine or the one my parents had in Buenos Aires. The foreground shows a man in a formal black suit, mounted by a half naked woman. It would usually be expected that the woman in such a photo would be excitingly beautiful. But this one isn't particularly beautiful. She is plain, so at a first glance, her face with glasses already completely clashes with her nudity. Like one of those strict teachers, buttoned up to their chins making it hard to imagine them bare-breasted. A bourgeois salon, suit, strict face of a naked woman - who is seeing all of this? In the corner under a table a little boy is hiding, staring at something forbidden to him. Forbidden, because it belongs to the adult world. If it weren't for his voyeur's gaze, the photomontage would be a satirical view of the bourgeois world and what is hidden beneath. But the boy's gaze disturbs the viewer because it changes the perspective: obviously the adults are not aware they are being watched. There is a glass partition between the boy and the adults, invisible on the photograph but completely visible to me then as well as now. Maman could be the strict teacher. Maman is also francesa, but the child - a girl - must under no circumstance find that out too soon. Because when she finds out, she will understand that's the only way to gain power over a man. Not even a boy should be looking at a scene intended for adults, because under the bourgeois appearance he is bound to discover the subversive world of erotica and its power. (translated from Croatian by Ivana Amerl)