viii. agreed action plan - Documents & Reports

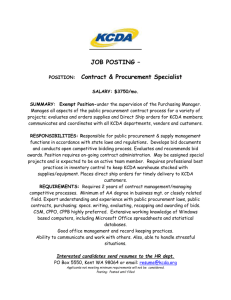

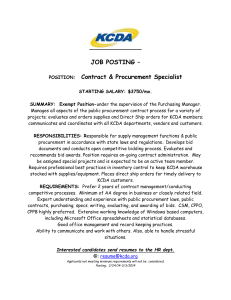

advertisement