Jerry, Paul_paper - AUSpace

*

Developing and implementing a continuing competence program for professional psychologists: A Canadian perspective

Paul Jerry, Associate Professor

Athabasca University

Past-President, College of Alberta Psychologists

1

Discusses the development of a continuing competence program for professional psychologists. Many North

American jurisdictions have mandatory continuing education that involves collecting continuing education hours in a determined period of time . The College of

Alberta Psychologists chose to develop and implement a continuing competence program that operates independent of credit hours. Psychologists engage in a self-determined and self-directed learning plan. The philosophical and theoretical assumptions behind such a program are presented, in contrast to other models of continuing education. Issues of professionalism and competence and the effect this program’s philosophy have had on the profession are discussed. Member feedback and participation data is presented as well as a discussion of the internal politics and external pressures the emerged during this development process.

*

Brief history

• So far, a 7 year project of the College

• Driven by the requirements of the Health

Professions Act

• Program constructed using combination of:

– understanding the evidence around competence

– watching other professions work through issues

– member consultation

– member-based subcommittee

– forms, declaration & training video

2

Philosophical Issues

• Teleology (consequential)

• Deontology (universals)

• Virtue (aligning with virtues)

• Relational (context, relationship, caring)

Issues of Principle

• Continuing Competence vs Continuing

Education

• Self-directed vs Regulator-directed

• Personal ownership vs Authoritarian compliance

*

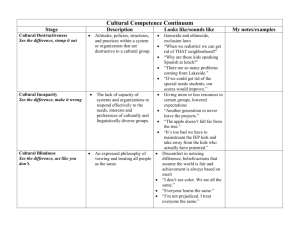

Defining Competence

• Begins with education

• Defined at initial registration

• Developed with supervision during provisional registration status

• Confirmed upon final registration

• Maintained over the career of the psychologist, by the psychologist

3

Working definition

• “ the habitual and judicious use of communication, knowledge, technical skills, clinical reasoning, emotions, values, and reflection in daily practice for the benefit of the individual and community being served ” [italics in the original](Epstein & Hundert, 2002, p.

228.)

* 4

*

What we have to do as psychologists:

Part 1

• Self-assessment

• Learning plan with learning objectives for the registration year and learning activities for the year

• Selfevaluation of the previous year’s learning plan including written confirmation of the learning activities completed

• Written declaration confirming that the learning plan has been followed

• Confirmation that the self evaluation and learning plan have been reviewed with another regulated member

5

*

What we have to do as psychologists:

Part 2

• On the request of the Registrar, the

Registration Committee, or the

Competence Committee, submit the learning plan and associated documents

• On request of the Registrar, the

Registration Committee, or the

Competence Committee, provide evidence of the activities identified in the member’s learning plan

6

What the College has to do

Establish a formal Competence Committee that will:

• periodically select regulated members in accordance with the criteria established by the Council for a review and evaluation of all or part of a regulated members continuing competence program

• 5% of membership sampled (actual number based on a power statistic, on current membership, approximately 350 programs

• Apply criteria to determine acceptability of a member’s plan

• Apply remedial interventions as necessary

* 7

*

How are plans evaluated?

• Comprehensive and reasonable

• Learning objectives clearly stated

• Relevant to practice area

• “Commonly accepted professional development activities”

• Supporting documentation

• Previous year’s learning evaluated

8

*

What happens if a program isn’t satisfactory?

• Complete specific competence program requirements

• Complete any additional learning activities

• Provide relevant information or evidence of continued learning and competence

• Submit to periodic review and evaluation

• Report on specified matters on specified dates

9

*

Competence Activities (pg. 1)

“frequently/very frequently”

• 93% Self-study

• 79% Peer consultation

• 72% Workshops/Conferences/Trainings

• 70% College/University courses

• 34% Providing teaching/training

• 27% Supervision

10

*

Competence Activities (pg. 2)

“frequently/very frequently”

• 23% Program planning/Evaluation

• 16% Research/Publications

• 12% Leadership/Voluntarism in psychology organizations

• 6% Journal clubs*

(may reflect unfamiliarity with the term used in the survey)

• 6% Other

11

*

Competence Activities Rated as

Most Beneficial

• 32% Workshops/conferences/seminars

(including on-line)

• 19% peer consultation

• 12% Reading

• 8% Self-study

12

Selected Bibliography

• Davis, D. (1998). Does CME work? An analysis of the effect of educational activities on physician performance or health care outcomes. International Journal of Psychiatric medicine, 28, 21-39.

• Epstein, R. M., & Hundert, E. M . (2002). Defining and assessing professional competence. Journal of the American Medical Association, 287(2), 226-235.

• Falender, C. A., & Shafranske, E. P. (2004). Clinical supervision: A competency-based approach. Washington, D.C.: American Psychological Association Press.

• Roberts, M., Borden, K., Christiansen, M, & Lopez, S. (2005). Fostering a culture shift:

Assessment of competence in the education and careers of professional psychologists.

Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 36 (4), 355-361.

• Truscott, D., & Crook, K. H. (2004). Ethics for the practice of psychology in Canada.

Edmonton: The University of Alberta Press.