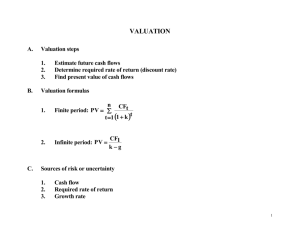

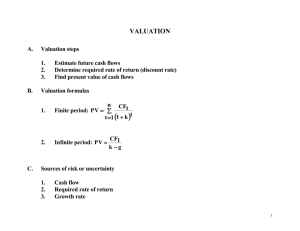

Capital Budgeting Processes And Techniques

advertisement

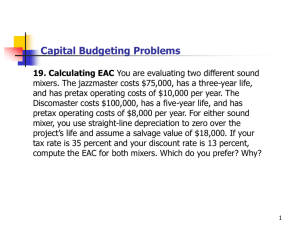

Chapter 8 Cash Flow and Capital Budgeting Professor XXXXX Course Name / # © 2007 Thomson South-Western Cash Flow and Capital Budgeting The kinds of cash flows that may appear in almost any type of investment How to deal properly with the problem of inflation in capital budgeting problems Special problems and situations that arise in the capital budgeting process The human element in capital budgeting 2 22 Cash Flow versus Accounting Profit In preparing financial statements for external reporting, accountants have a different purpose in mind than financial analysts have when they evaluate the merits of an investment. Accountants measure the inflows and outflows of a business’s operations on an accrual basis rather than on a cash basis. E.g., 3 33 depreciation Cash Flow versus Accounting Profit For capital budgeting purposes, financial analysts focus on incremental cash in-flows and outflows. This emphasis simply recognizes that no matter what earnings a firm may show on an accrual basis, it cannot survive for long unless it generates cash to pay its bills. calculating a project’s NPV, analysts should ignore the costs of raising the money to finance the project. When 4 44 The Initial Investment Many capital budgeting problems begin with an initial outflow to acquire/install fixed assets. Must also consider: Cash inflow from selling old equipment Cash inflow (outflow) if selling old equipment below (above) tax basis generates tax savings (liability) An example.... Tax rate = 40% New equipment costs $10 million, $0.5 million to install Old equipment has been fully depreciated, sold for $1 million The initial investment would then be an outflow of $10.5 million, and an after-tax inflow of $0.60 million from selling the old equipment 5 55 Types of Cash Flows Depreciation Fixed asset expenditures Working capital expenditures Terminal value Incremental cash flow 6 66 Depreciation Largest noncash item for most investment projects Affects the amount of taxes the firm will pay Modified accelerated cost recovery system (MACRS) defines the allowable annual depreciation deductions for various classes of assets 7 77 Depreciation Many countries allow firms to use one depreciation method for tax purposes and another for reporting purposes Accelerated depreciation methods (such as MACRS) increase the present value of an investment’s tax benefits Relative to MACRS, straight-line depreciation results in higher reported earnings early in an investment’s life Which method would you expect companies to use when they file their taxes, and which would they use when preparing public financial statements? 8 For capital budgeting analysis, it is the depreciation method for tax purposes that matters 88 Two Methods Of Handling Depreciation To Compute Cash Flow Adding non-cash expenses Find after-tax profits, add back Assume a firm purchases a fixedcharge asset back to after-tax earnings non-cash taxtoday savings for Sales $30,000 Cost of goods (10,000) $30,000 Sales Cost of goods $30,000 (10,000) Gross profits $20,000 over 3 years Pre-tax income $20,000 Plans to depreciate using straight-line method Depreciation (10,000) Taxes (40%) (8,000) Pre-tax income $10,000 Taxes Firm(40%) will produce(4,000) 10,000 units/year 9 99 Net income $6,000 Cash flow = NI + deprec $16,000 Aft-tax income $12,000 Depreciation tax savings $4,000 Costs $1/unit Sells for $3/unit Cash Flow $16,000 and most common technique: Firm pays taxes at Simplest a 40% marginal Add depreciation back inrate Tax Depreciation Schedules by Asset Class 10 10 10 Fixed Asset Expenditures When a firm sells an old piece of equipment, there will be a tax consequence of the sale if the selling price exceeds or falls below the old equipment’s book value. If the firm sells an asset for more than its book value, the firm must pay taxes on the difference. If a firm sells an asset for less than its book value, then it can treat the difference as a tax-deductible expense. 11 11 11 Working Capital Expenditures Many capital investments require additions to working capital Net working capital (NWC) = current assets minus current liabilities Increase in NWC is a cash outflow; decrease a cash inflow • An example… – – – – 12 12 12 Operate booth from November 1 to January 31 Order $15,000 calendars on credit, delivery by Nov 1 Must pay suppliers $5,000/month, beginning Dec 1 Expect to sell 30% of inventory (for cash) in Nov; 60% in Dec; 10% in Jan – Always want to have $500 cash on hand Working Capital For Calendar Sales Booth Oct 1 Nov 1 Dec 1 Jan 1 Feb 1 Cash $0 $500 $500 $500 $0 Inventory $0 $15,000 $10,500 $1,500 $0 Accts payable $0 $15,000 $10,000 $5,000 $0 Net WC $0 $500 $1,000 ($3,000) $0 Monthly in WC NA +$500 +$500 ($4,000) +$3,000 Payments and inventory 13 13 13 Oct 1 to Nov 1 Nov 1 to Dec 1 Dec 1 to Jan 1 Jan 1 to Feb 1 Reduction in inventory $0 $4,500 [30%] $9,000 [60%] $1,500 [10%] Payments $0 ($5,000) ($5,000) ($5,000) ($500) ($500) +$4,000 ($3,000) Net cash flow Terminal Value Terminal value used when evaluating an investment with indefinite life-span Construct cash-flow forecasts for 5 to 10 years Forecasts more than 5 to 10 years have high margin of error; use terminal value instead • Terminal value is intended to reflect the value of a project at a given future point in time 14 14 14 – Large value relative to all the other cash flows of the project Terminal Value Different ways to calculate terminal values – Use final year cash flow projections and assume that all future cash flows grow at a constant rate – Multiply final cash flow estimate by a market multiple – Use investment’s book value or liquidation value JDS Uniphase cash flow projections for acquisition of SDL Inc. Year 1 $0.5 Billion 15 15 15 Year 2 $1.0 Billion Year 3 $1.75 Billion Year 4 $2.5 Billion Year 5 $3.25 Billion Terminal Value of SDL Acquisition If we assume that cash flow continues to grow at 5% per year (g = 5%, r = 10%, cash flow for year 6 is $3.41 billion): CFt 1 $3.41 PVt , or PV5 $68.2 rg 0.10 0.05 Terminal value is $68.2 billion; value of entire project is $0.5 $1 $1.75 $2.5 $3.25 $68.2 $48.7 1 2 3 4 5 5 1.1 1.1 1.1 1.1 1.1 1.1 16 16 16 $42.4 billion of total $48.7 billion from terminal value Using price-to-cash-flow ratio of 20 for companies in the same industry as SDL to compute terminal value Terminal Value = $3.25 x 20 = $65 billion Caveat : market multiples fluctuate over time Incremental Cash Flow Incremental cash flows versus sunk costs Capital budgeting analysis should include only incremental costs • An example… 17 17 17 – Norman Paul’s current salary is $60,000 per year and expect increases of 5% each year – Norm pays taxes at flat rate of 35% – Sunk costs: $1,000 for GMAT course and $2,000 for visiting various programs – Room and board expenses are not incremental to the decision to go back to school Incremental Cash Flow At end of two years assume that Norm receives a salary offer of $90,000, which increases at 8% per year Expected tuition, fees and textbook expenses for next two years while studying in MBA: $35,000 If Norm worked at his current job for two years, his salary 2 would have increased to $66,150: $60,000 1.05 $66,150 Yr 2 net cash inflow: $90,000 - $66,150 = $23,850 After-tax inflow: $23,850 x (1-0.35) = $15,503 3 Yr 3 cash inflow: $90,000 1.08 $60,000 1.05 1 0.35 $18,032 MBA has substantial positive NPV value if 30 yr analysis period What about Norm’s opportunity cost? 18 18 18 Opportunity Cost In capital budgeting, the opportunity costs of one investment are the cash flows on the alternative investment that the firm decides not to make. 19 19 19 Opportunity Costs Cash flows from alternative investment opportunities, forgone when one investment is undertaken If Norm did not attend MBA, he would have earned: First year: $60,000 ($39,000 after taxes) 20 20 20 Second Year: $63,000 ($40,950 after taxes) NPV of a project could fall substantially if opportunity costs are recognized Cash Inflows, Discounting, and Inflation If inflation is in the numerator, be sure that it is also in the denominator. The nominal return reflects the actual dollar return. The real return measures the increase in purchasing power gained by holding a certain investment. In general, when the inflation rate is high, so too will be the nominal rate of return offered by various investments: 21 21 21 If the numerator ignores inflation, so too must the denominator. Investors will demand a return that not only keeps pace with inflation, but also offers a positive real return. Inflation Rule 1 Nominal cash flows reflect the same inflation rate that the interest rate does Inflation Rule 1 — When we discount cash flows at a nominal interest rate, embedded in the discount rate is an estimate of expected inflation. 22 22 22 Inflation Rule 2 Occasionally an investment’s cash flow projections may be stated in real terms. Real cash flows only reflect current prices and do not incorporate upward adjustments for expected inflation. Inflation Rule 2 — When project cash flows are stated in real rather than in nominal terms, the appropriate discount rate is the real rate. 23 23 23 Equipment Replacement and Unequal Lives A firm must purchase an electronic control device First alternative is a cheaper device, higher maintenance costs, shorter period of utilization Second device is more expensive, smaller maintenance costs, longer life span Expected cash outflows Device A B 1 1500 1200 2 1500 1200 3 1500 1200 4 1200 Maintenance costs are constant over time. Use real discount rate of 7% for NPV Device A B 24 24 24 0 12000 14000 NPV $15,936 $18,065 Cash outflow device A < cash outflow device B select A? Equivalent Annual Cost (EAC) 25 25 25 EAC converts lifetime costs to a level annuity; eliminates the problem of unequal lives 1. Compute NPV for operating devices A and B for their lifetime NPV device A = $15,936 NPV device B = $18,065 2. Compute annual expenditure to make NPV of annuity equal to NPV of operating device Device A X X X $15,936 1 2 1.07 1.07 1.07 3 Device B $18,065 Y Y Y Y 1.071 1.07 2 1.07 3 1.07 4 X $6,072 Y $5,333 Capital Budgeting and Inflation 26 26 26 Special Problems in Capital Budgeting Equipment replacement and equivalent annual cost Excess capacity 27 27 27 Operating and Replacement Cash Flows for Two Devices 28 28 28 Excess Capacity When firms operate at less than full capacity, managers encourage alternative uses of the excess capacity because they view it as a free asset. The marginal cost of using excess capacity is zero in the very short run, but using excess capacity today may accelerate the need for more capacity in the future. When this is so, managers should charge the cost of accelerating new capacity development against the current proposal for using excess capacity. 29 29 29 Excess Capacity Excess capacity – not a free asset as traditionally regarded by managers Company has excess capacity in a distribution center warehouse In two years the firm will invest $2,000,000 to expand the warehouse The firm could lease the excess space for $125,000 per year for the next two years Expansion plans should begin immediately in this case to hold inventory for stores that will come on line in a few months Incremental cost – investing $2,000,000 at present vs. two years from today Incremental cash inflow - $125,000 30 30 30 Excess Capacity NPV of leasing excess capacity (assume 10% discount rate) 125,000 2,000,000 NPV 125,000 2,000,000 $108,471 2 1.10 1.1 NPV negative – reject to lease excess capacity at $125,000 per year The firm could compute the value of the lease that would allow to break even X 2,000,000 NPV X 2,000,000 0 2 1.10 1.1 31 31 31 X = $181,818 Leasing the excess capacity for a price above $181,818 would increase shareholders wealth Human Face of Capital Budgeting The best financial analysts can provide not only the numbers to highlight the value of a good investment, but also can explain why the investment makes sense, highlighting the competitive opportunity that makes one investment’s NPV positive and another’s negative. 32 32 32