Valuation Models

advertisement

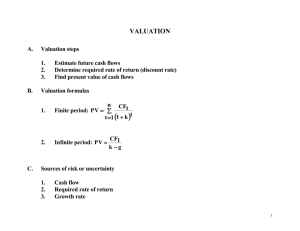

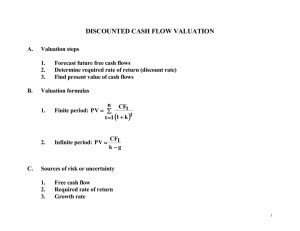

VALUATION A. Valuation steps 1. 2. 3. B. C. Estimate future cash flows Determine required rate of return (discount rate) Find present value of cash flows Valuation formulas 1. n CF t Finite period: PV t t 1 1 k 2. Infinite period: PV CF1 k g Sources of risk or uncertainty 1. 2. 3. Cash flow Required rate of return Growth rate 1 D. Applications of valuation 1. 2. 3. 4. Bonds and stocks Capital budgeting Leasing Mergers and acquisitions Methods of evaluating projects 1. Net Present Value (NPV) n CF t (where the initial cash flow is usually negative) t t 0 1 k 2. Internal Rate of Return (IRR) n CFt CF0 t t 1 1 IRR 3. Modified Internal Rate of Return (MIRR) n nt CFt 1 k t 1 CF0 n 1 MIRR 2 4. Payback = Year before full recovery + (Uncovered cost at start of year/Cash flow during year) ex: CF0 = -2,000, CF1 = 1,800, CF2 = 500: Payback = 1 200 1.4 years 500 CAPITAL BUDGETING CONCEPTS In capital budgeting, you compute the incremental free cash flows (the cash flows available to the investors): Changes in operating cash flow -Changes in capital spending -Changes in net working capital =Changes in free cash flow 3 1. Operating Cash Flow Revenues Operating costs (Be sure to include effects on revenues and operating costs in other parts of the company and incremental overhead or administrative costs) Taxes (Include the tax effects of depreciation but not depreciation itself) 2. Investment (Capital Expenditures) Purchases and sales of assets Include any tax effects of sales Opportunity cost of assets already owned that are employed 3. Changes in net working capital include Sales and purchases on credit (accounts receivable and payable) 4 Changes in inventories of materials and finished goods Reserves of cash TAXES AND CAPITAL BUDGETING Taxes are the part of capital budgeting that makes things complicated. Because of tax laws, we have to worry about whether certain effects are taxable and how much tax they incur. One example is depreciation, which is a charge to earnings (a quasi-expense), but not an actual cash flow. Another example is the sale of an asset. Whenever you sell an asset, you pay taxes on any "profit" from the sale. Uncle Sam defines profit as: Profit = Selling Price - Book Value (where Book Value = Installed Cost of Asset Accumulated Depreciation) Ex: If you sell an asset for $10,000, the book value is $6,000, and your tax rate is 40% then: Profit = $10,000-$6,000=$4,000 and your net cash inflow is: $10,000-.40($4,000)=$8,400. 5 A Typical Profile of Cash Flows: Initial outlays or cash flows Purchase and installation of assets Intermediate cash flows Revenues minus expenses net of tax effects Terminal cash flows Proceeds from sale of assets net of tax effects Changes in net working capital Changes in overhead expenses net of tax effects Costs of clean up or disposal net of tax effects Depreciation tax shields Recovery of working capital Training expenses net of tax effects Sale or disposal of replaced assets net of tax effects Most projects usually exhibit a normal cash flow pattern, meaning that the initial cash flow is negative, followed by a series of cash inflows. A nonnormal cash flow pattern is one in which an initial negative cash flow is followed by a series of inflows and outflows. Note about net working capital: Changes in net working capital frequently accompany capital expenditure decisions. The recovery of working capital in the terminal cash flow occurs because at the end of the project’s life the need for increased net working capital investment is assumed to end. 6 Always ask the "with vs. without" question! The "with vs. without" rule says to always ask whether a particular cash flow is different with versus without the project. If the answer is "yes" then include it in your project analysis; otherwise leave it out. Typical items that do not get included are sunk costs and overhead expenses. However, incremental overhead expenses would be included. Things to keep in mind when computing incremental cash flows: Include changes, not levels, of net working capital Include the recovery of net working capital at the termination of a project Ignore costs that are not incremental (i.e., sunk costs and pre-committed expenditures) Ignore financing cash flows such as interest payments and dividends Include only overhead costs that are incremental to the project Include the opportunity cost of owned assets that are employed in a project Include the tax effects of the sale of assets 7 Include effects on the sales and costs of production of related products or services of the company Ignore depreciation charges, but include the tax effects of depreciation Treat inflation consistently (i.e., discount nominal cash flows by nominal discount rates) Inflation adjustments 1. 2. Real versus nominal cash flows Real versus nominal discount rates Is inflation neutral? a. Depreciation is invariant to inflation b. Price inflation c. Cost inflation 8 COMPUTING THE DISCOUNT RATE 1. If the project is a scale expansion of the existing business, then the WACC is usually sufficient: WACC w dk d 1 T w pk p w sk s (d= debt, p=pfd. stock, and s=common stock) 2. If the risk of the project is different from the risk of the firm then you should use a risk-adjusted discount rate (RADR). One way of doing this is with the CAPM: Assign a beta to the project Establish risk classes within the firm and assign betas accordingly Look at companies with similar projects (may need to unlever beta--see M&A discussion) Use CAPM to compute the discount rate: k i k RF i (k M k RF ) 9 OTHER PROJECT RISK ISSUES 1. Stand-alone risk: measures the risk the project would have it if were the firm's only asset. It is measured by the variability of the asset's expected return. Sensitivity Analysis Simulation CV as a measure of risk: NPV ENPV 2. Within-firm risk: reflects the effects of a project on the firm's risk, and it is measured by the project's effect on the firm's earnings variability. 3. Market risk: reflects the effects of a project on the riskiness of stockholders, assuming they hold diversified portfolios. It is measured by the project's effect on the firm's beta coefficient. 10 MERGERS AND ACQUISITIONS A. Sources of synergy 1. 2. 3. 4. Operating economies of scale Financial economies of scale Differential managerial efficiency Increased market power B. Friendly versus hostile merger C. Cash flows 1. 2. D. Capital budgeting – all cash flows (to both equity and debt holders) Mergers and acquisitions – equity cash flows Discount rate 1. 2. Capital budgeting – weighted average cost of capital Mergers and acquisitions – cost of equity 11 VALUING THE TARGET FIRM 1. Discounted cash flow analysis a. Pro forma cash flow statement 2006 2007 $4,000,000 $6,000,000 $7,500,000 $8,500,000 2,000,000 3,000,000 3,750,000 4,250,000 Depreciation 400,000 450,000 500,000 550,000 S&A expense 300,000 400,000 500,000 600,000 Interest expense 200,000 300,000 300,000 400,000 $1,100,000 $1,850,000 $2,450,000 $2,700,000 440,000 740,000 980,000 1,080,000 $660,000 $1,110,000 $1,470,000 $1,620,000 400,000 450,000 500,000 550,000 Cash flow $1,060,000 $1,560,000 $1,970,000 $2,170,000 Retentions 0 500,000 400,000 300,000 $1,060,000 $1,060,000 $1,570,000 $1,870,000 Net sales Cost of goods sold EBT Taxes Net income Add depreciation Available CF 2008 2009 12 b. Estimating the discount rate (Hamada Equation) bU bL D 1 1 T S D b L b U 1 1 T S Assume the target firm's beta is 1.20, its capital structure consists of 40% debt, and the corporate tax rate is 30%. The acquisition will increase the debt ratio to 50% and the tax rate to 40%. The risk-free rate is 6% and the market return is 15%: bU 1.20 .40 1 1 .30 .60 0.82 (asset beta of target firm) .50 b L 0.821 1 .40 1.31 (relevered beta w/new capital structure) . 50 k s .06 1.31.15 .06 0.1779 13 c. Valuing the cash flows Estimating the terminal value: This can be done using the Gordon (constant growth) model or market multiples (see pg. 115 in text--section 3.5.1) We'll assume a 5% annual growth rate after 2009: TV2009 CF0 CF1 CF2 CF3 CF4 I NPV = = = = = = CF2009 1 g 1,870,0001 .05 $15,351,837 .1779 .05 ks g $0 $1,060,000 $1,060,000 $1,570,000 $1,870,000 + $15,351,837 = $17,221,837 = 17.79% $11,570,917 d. Setting the bid price: If there are 1,000,000 shares outstanding then: P $11,570,917 $11.57 1,000,000 14