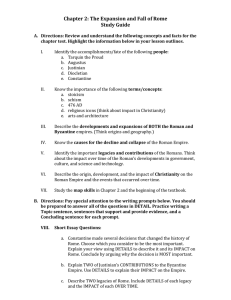

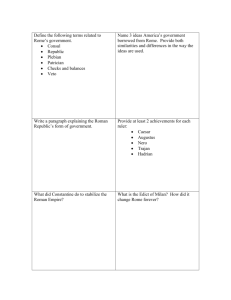

Chapter 1 Reading Notes

advertisement

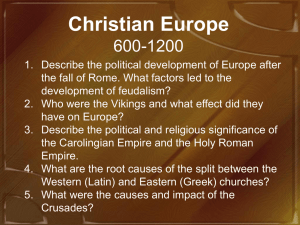

Chapter 1 Reading Notes: The Beginnings of European History The purpose of AP European History is to study the foundations of the modern world, the world as we know it today, through the perspective of Europeans and those they came in contact with over time. In so doing, we must define what we mean by modern European history because some of the concepts and time periods discussed will undoubtedly appear very archaic. In terms of our study, the word modern refers to both a time frame (in this case 1450 through the present) and also a complicated way of living in which we rely on technology, government institutions, and a vast network of connections among countries commonly referred to as globalization. Thus, throughout our study of European history, we will focus on the political, economic, religious, social, intellectual, and artistic institutions that have developed over time (since 1450) to produce the world we live in today. Nevertheless, in order to understand the development of these institutions, we have to go back a little farther in time in order to understand how Europe advanced to the point where we start recognizing it as Europe. Greece The foundations of European civilization are often cited in the development of the Greek civilization starting as early as 1900 BC when Indo-European speaking peoples invaded the older Cretan civilization on the Aegean Sea. Though not modern by any sense, this was an essential development because all European languages spoken today (with the single exception of Basque) fall into the Indo-European language group which leads geographers to believe that the languages all have a common ancestry. By 1300 BC, these invading peoples occupied most of the area now known as Greece. The Greeks were talented in many ways; they took ideas from everywhere and improved upon them. The Greeks developed city-states such as Athens, Corinth, and Sparta. Each city-state was like its own little country with very different political, social, and military institutions in each. The Greeks sought to understand the natural world around them in a systematic fashion and wrote down what they could. Many Greek ideas in science, medicine, logic, and politics were accepted in Europe until the Scientific Revolution starting in the 1500s. Most Greek thought was developed during what was known as the Hellenic Era after Philip of Macedon had conquered the Greek city-states and his son, Alexander the Great, had conquered much of the known world up to that point. During the Hellenic Era, Greek ideas spread throughout the empire, particularly influence the next civilization of note: the Romans Rome In 146 BC, the Romans conquered Greece and adopted the Greeks into their everyexpanding Republic. In 31 BC, the Roman Republic became the Roman Empire which would last until about the fifth century AD. One of the main goals of the Roman Empire was to increase power and influence through continual expansion. The most significant influence that the Romans had on conquered territories was political. Although territories were allowed their own customs, Roman law was considered higher than the customs of any territory. If a dispute could not be solved at the local level, then Roman law was enforced. Romans believed that there was universal truth in the world and their law was based on what the government thought was best for all. This does not mean all the laws were equal; many people (including slaves and women) did not have citizenship within the Empire and were thus excluded from many aspects of political life. European laws were based on this model for centuries. The success of the Empire depended on many things including prosperous trade among regions of the Empire as well as the ability of the military to defend the Empire against invasion. During its peak, the Roman Empire became famous for the pax Romana or Roman peace. Within the Empire, there was very little conflict which made people happy because they did not have to fear for their lives at every moment. Trade was facilitated by the use of Latin as the national language. Latin was spoken by people of all ethnic groups throughout the empire including the ancestors of modern European countries. The Romance languages of Italian, Spanish, French, Portuguese, and Romanian are all Latin-based. Over several centuries, the Empire started to fall apart due to internal pressures and external pressures. One of the earliest internal pressures was the advent of Christianity. Christians followed the leader Jesus of Nazareth whom they believed to be the Savior of the world. After the death of Jesus, the religion was spread throughout the empire by his very loyal followers, the apostles. Initially, Christianity appealed to the poor and those at the bottom of Roman society because it taught that all men and women were created equal and therefore should help and serve one another. Christianity was considered very dangerous in the Roman Empire because the Roman Emperor, by law, was considered a god and the people of the Empire were expected to worship him as head of state and head of religion. When one leader is both the political and religious leader of a country, it is known as casearopapism (think king is the pope). By the 3rd century AD, Christians were persecuted heavily for their beliefs yet the movement continued to spread. In the 4th century (perhaps the year 312), the Roman Emperor Constantine accepted Christianity in order to quell the mass violence that was tearing the empire apart. By the 5th century, Christianity was the only religion tolerated in the Roman Empire. It is not possible to overstate or overestimate the impact of Christianity on European development. The Christian church and leaders in Europe often had more power over the people than political leaders such as kings for the next 1000 years. Aside from the internal conflicts, the Roman Empire had to contend with external conflicts as well. In order to better deal with these external pressures, the Emperor Constantine split the Empire into two halves in 330 AD. The western half was considered less civilized, more isolated, and its capital remained at Rome. The eastern half was the more advanced part of the empire that was still able to trade with merchants from the Middle East and North Africa. Its capital became Constantinople and after the Roman Empire completely fell apart in the fifth century, the eastern portion became the Byzantine Empire which lasted until 1453 when it was overtaken by the Ottoman Turks. After the split, barbarians (a term that means anyone who did not speak Latin) started to invade the Roman Empire. Though both halves were subject to these pressures, the western portion seemed less able to defend against outsiders. In 450, the Empire was invaded by a group of people known as the Huns who came from Central Asia. Other invaders included Germanic people from northern and western Europe (including the Goths, Visigoths, Ostrogoths, Saxons, Franks, and Vandals). By the seventh century, the Arabs had also had a revival and started to put pressure on the Roman Empire. This revival was mostly due to the advent of the religion Islam. Followers of Islam believed in the teachings of the prophet Mohammed who was the direct spokesman for God. His teachings, though not initially well-accepted in his hometown of Mecca, eventually became extremely popular and spread very rapidly throughout the Middle East among Arabicspeaking people. Islam, like Christianity, was a universalizing religion which meant that its followers believed that everyone should belong to that one true religion. Throughout the 600s, Islam spread throughout the Arabic world (including the Middle East and North Africa) and was putting pressure on the Byzantine Empire. By the 700s, all of the Iberian Peninsula (Spain and Portugal) was Islamic, having been converted by Arabic invaders. After all these invasions, the Roman Empire was no more. After the fall of Rome, invasions became even more frequent. Invasions of Europe continued to take place in the 1200s by the Tartars (a group from central Asia) and in the 1300s by the Ottoman Turks. The Successors of Rome The Roman Empire, thus pressured by internal and external conflict broke into three main parts. The first part was the Byzantine Empire which continued to thrive as a crossroads for trade until it fell to the Ottoman Turks over 1000 years later. The second part was the Islamic Empire which was built up by the successors of Mohammed. This Empire included much of the Middle East and all of North Africa, extending as far as Spain at its peak. The Empire would have continued to expand into the rest of Europe had the Spanish Muslims (called Moors) not been halted at the battle of Tours in 732. The Islamic Empire was known for its advances in medicine, art, architecture, and scholarship. Muslim scholars would find ancient Greek manuscripts and copy them into Arabic to preserve them for later generations. They also developed Arabic numerals which made arithmetic, which had been complex at best with Roman numerals, easy enough to teach to youth. The Islamic Empire, like the Byzantine Empire, was known for its trade with the rest of the known world. Muslim merchants could receive and sell goods from as far as East Africa, India, and even China. The final part of the Roman Empire, the part from which Europe emerged, was the western part of the former Roman Empire. By 500 AD, this part was in complete shambles. The West was ruled by various barbarian kings that ruled groups no larger than tribes in relative geographic isolation from the other tribes. There was a strong Germanic influence as a result of all the invasions and feudalism began to be the political and economic structure of choice. There was no money and virtually no trade. This is one of the reasons the time from 500800 is known as the Dark Ages. The only surviving institution from Rome was the Christian Church organized under a network of church leaders known as bishops. Monasteries became very popular because religious people could escape from the rather violent world around them and live in peace in a sheltered environment. The bishop of Rome was eventually deemed to have more spiritual authority than other bishops as a result of the Doctrine of Petrine Succession. This doctrine said that Jesus had left the authority inherent in Christianity to his apostle Peter who in turn left that supreme authority for the Church to the bishop of Rome. From then on, the bishop of Rome could trace back his authority to Peter and therefore Christ which meant that other Church leaders should look to Rome for authority. The bishop of Rome took on the title pope and separated himself from political influence by secular (non-religious) kings. The pope could only be elected by other church officials known as cardinals. The pope also kept kings out of Rome by claiming a document called the Donation of Constantine. This document essentially said that a large part of the city of Rome was donated to the Christian Church to be administered by the pope by the first Christian emperor, Constantine. The document provided a legal reason for the Church and state to be administered by separate people in European countries. The document, however, was proved to be a fake (not written by Constantine) during the Renaissance (a story we will get to later). The Church sent out missionaries to convert those tribes or groups of people that did not yet believe in Christianity. Although important in European history, this was a relatively slow process that started in Rome and spread out from there. One of the first kings to be converted was Clovis I (a Frank) whose successors would later rule France. Perhaps the most famous descendent of Clovis I was the Frankish king Charlemagne. In 800, Charlemagne made a deal to protect the pope in exchange for the pope’s blessing. Charlemagne was thus crowned “Holy Roman Emperor” by the pope thereby become the first Roman Emperor in hundreds of years. Charlemagne ruled from his capital at Achaen in France. His empire included modern-day France, parts of Italy, and parts of Germany. It was unceremoniously divided by his grandchildren in the Treaty of Verdun in 843 causing conflicts for the next 1200 years (like WWI and WWII, but I’m skipping ahead). Nevertheless, Charlemagne remained important because he wanted to bring back the concept of a powerful western empire much like Rome had once been. He also valued education, though he could barely read and never learned to write. Much learning had been lost during the violence following the fall of Rome. Charlemagne used his influence to revive the use of Latin. He had scholars and clergy come from all across Europe to copy and recopy disintegrating manuscripts to be used later. They even developed a new form of writing known as Carolingian miniscule that used smaller letters. The small letters in the modern Western alphabet developed from this writing. Despite the advances of Charlemagne, Western Europe still lagged far behind its eastern counterparts. Invasions continued in the 800s by the Norse (aka Vikings or Danes). In the 900s, the Magyars (or Hungarians) invaded from Asia. These groups were eventually converted to Christianity and assimilated into the older invaders throughout Europe. For example, the pope sent the leader of the Magyars, King Stephen, a golden crown in order to convince him to convert and stop invading the rest of Europe. By about 1000, Europe as we know it today began to form. From 1000 to about 1400 was known as the High Middle Ages. This was the time of the greatest growth and advancement that had occurred since the time of the Roman Empire. The development began with new inventions that improved agricultural output. One of these inventions was the horse harness that allowed the weight of a plow to be distributed about a horse’s shoulders and allowed more than one animal to be harnessed together making animal power more useful. The other invention was the three-field system in which farmers in a village would combine their land into three fields. They would plant one field with one crop (like wheat), another field with another crop (like barley), and leave the third field fallow to replenish its nutrients. The fields would be rotated every year. These agricultural inventions led to population growth. Feudalism During this time a political and economic system called feudalism developed. Feudalism is essentially a contract between two people: a lord and a vassal. A lord is someone who owns land and has the resources to protect those who live on the land. A lord promises a vassal land to use and protection from invaders (obviously all too common in the Middle Ages). A lord would usually have several vassals because he could not work all the land he owned on his own. Therefore, the lord would also hold a court for his vassals if there was a dispute. This court was also to be a council to advise the lord, though he did not have to accept the ideas of the vassals. In exchange, the vassal pays dues to the lord in the form of loyalty and military service. A vassal would be required to serve in the lord’s military for a certain number of days a year. If the lord was kidnapped, the lord’s vassals would have to pay the ransom. When a vassal died and his son inherited the land, the vassal’s son would pay an inheritance fee. If the lord’s children married, the vassals would pay a fee. Thus feudalism was an exchange of land for loyalty. At the bottom of this feudal system was a vast network of serfs. Serfs were kind of like vassals to the vassals of the bigger lord. Serfs promised to work the land and give loyalty to whoever owned the land (whether it be the lord or the vassal). This usually meant that the serfs rent the land in exchange for working on the lord’s land for a certain number of days a year. Serfs were bound to the land; they could not leave without permission from the lord. Serfs had virtually no rights other than what was allowed them by the lord. In the feudal system, lords and serfs lived on manors. A manor was a piece of land owned by a lord (remember this lord could be a vassal to another lord who owned more land). A manor was its own self-sufficient area. The lord lived in an estate, sometimes called a manor house or a keep, on a large part of the land. The serfs were required to work on the lord’s land for part of the year. Some of the land was rented out to serfs who worked their land when they were not working for the lord. A small portion of the land was set up as a village where the goods the people on the manor needed were produced (ex. blacksmith, butcher, tanner, etc.) Manors were self-sufficient and rarely communicated nor traded with other manors. People were very isolated during the Middle Ages. As mentioned above, the population of Europe during the High Middle Ages started to grow due to advances in agriculture. This population growth led to strained resources on manors where there was a limited supply of land. Consequently, lords would sometimes offer incentives to serfs who were willing to cultivate new lands. These incentives led to increased freedom for serfs, particularly the freedom to move off the land without permission from the lord. As a result, feudalism started to wane in Western Europe around the fourteenth century. In Eastern Europe, however, serfdom became more deeply entrenched during this timed. Even serfs in Western Europe who gained freedom of movement still owed manorial dues to the lord which would be a continuing cause of conflict even past the French Revolution. Feudalism led to the development of early monarchies. If someone owned enough land and had enough vassals, he might become king by asserting his authority over his vassals. For example, in France Hugh Capet became king in 987. His descendants, known as the Capetian kings of France, ruled until the French Revolution. Similarly, the Germanic princes got together to elect a Holy Roman Emperor that had the rights of king over central Europe. The Holy Roman Emperor had less control over the people he ruled, though, since he was elected by his vassals and could be removed by them if he was not doing a good job. Another example would be the development of the English monarchy. It began in 1066 when William of Normandy invaded England and established a very efficient model of feudalism throughout the country. English vassals were thus very loyal because they were all hand-picked by the king. These monarchies were by no means as strong as we think of today in terms of political power. Throughout the 1200s, vassals of these kings insisted that their historic feudal right to the council the king not be violated. Perhaps the most famous of these disputes between vassals and king was the advent of the Magna Carta in 1215. The vassals of King John of England kidnapped the king and forced him to sign the Magna Carta ensuring their right to council the king. In England, this specifically meant that the king could not raise taxes without the consent of a council (in this case, parliament). Virtually every country in Europe developed some sort of group that was set up to balance the power of the king. In England, it was called parliament; France had estates, the Holy Roman Empire had diets, and Spain had cortes. Despite the different names, these groups all had the purpose of ensuring that the king was somehow responsible to the people within his realm. They all had varying degrees of success, but the English parliament seemed to be the most effective at controlling the king because it was made not only of the kings vassals but of wealthy merchants that held power in towns. The English parliament was also successful in that the people were bound to the decisions of their representatives. If a representative voted for a law, then the people who had sent that representative were bound to observe the law whether each individual agreed or not. Trade Although most areas were isolated during the Middle Ages, trade along the Mediterranean started to increase in the 13th century. The Italian city-states of Venetia, Genoa, and Pisa were well-known for their merchants and access to goods from the east. These goods were highly valued by Europeans because they could not be produced in Europe at the time. This included things like china, silk, and spices brought from afar. Some Europeans even went so far as to explore trade routes to the east. For example, the famous Marco Polo of Venice traveled the Silk Road and lived in China from 1275-1292. Reports from Polo and others led to a keen curiosity among Europeans about what else they could get from the east. As merchants started selling these goods throughout Europe, towns started to develop along the important trading routes. These towns would get a charter from the king or ruling authority and therefore not be subject to the rules that existed on manors. The people of towns had corporate liberties which meant that they were not required to serve the lords of manors and they paid taxes directly to the king for these liberties. Corporate liberties were not individual human rights but rather communal rights that all people in a town could rely on. This concept of freedom, especially freedom of movement, was appealing to many serfs. There was even a law that said if a serf escaped from a manor and lived in a free town for over a year, then the serf could not be required to return to the manor. Towns were mostly run by the leaders of various guilds. Guilds were monopolies on certain products produced in a town. For example, in each town there would be a cloth weaver’s guild and a glass-workers guild and so on. Guilds strictly controlled who could enter a profession by using an apprenticeship system. A person would serve as an apprentice for a specified length of time (usually 5-10 years), and then that apprentice could become a journeyman and work in that town or another in that profession. If the journeyman worked long enough and hard enough, he could become a master of the guild which gave him significant political sway in the town but also the ability to choose and train apprentices. Guilds were effective in that they controlled how many people could enter a profession thereby keeping wages high. They also looked after the needs of guild members and their families. The widow of a guild member could expect the guild to take care of her and her children thus taking care of some social services that we expect today. Unfortunately, guilds were also monopolies which meant that no one could sell their products unless they belonged to the guild. It also meant that the guild determined how much a product should cost whether the people of Europe could afford that price or not. Guilds were a major economic force up until the Industrial Revolution in Europe (much later). The purpose of towns revolved around trade, but they became important to kings because the town merchants became very wealthy over time. In the feudal system, there was no power given to those with money that were not vassals of the king. Thus, these wealthy merchants had little political power, and they were constantly striving for more sway with the king. Sometimes the towns or “free cities” would join together to become even more politically influential. The most famous of these collaborations was the Hanseatic League in the northern free cities in the Holy Roman Empire. Leagues such as the Hanseatic League could work together to develop money and financial systems across large areas- a significant step toward modernity. The Church in the Middle Ages Up to this point we have mentioned very little about the Christian Church of Medieval Times unless it was necessary. Nevertheless, the Church was probably the most influential institution in the lives of ordinary people during the Middle Ages. Everything in life revolved around the Church and finding individual salvation while living a rather brutal existence for most. Many people died young and most were looking for something to hope for in life after death. Before the 1000, the power of the pope was significantly limited throughout Europe. A significant blow came to the Christian Church in 1054 as a result of the Great Schism. At this time there were two main bishops that both claimed authority over the Christian Church: one in Rome and one in Constantinople. Usually, these two bishops got along, but in 1054 the bishops had a debate over whether icons (figures or statues of Christ, the Virgin Mary, and various saints) could be used by Christians to help them worship. Because of the debate, both bishops excommunicated the other and leaders of countries had to choose which bishop to follow. The bishop of Rome became the leader of the Roman Catholic Church which most countries in Europe followed until the Reformation. The bishop of Constantinople became leader of the Eastern Orthodox Church which Greece, the Byzantine Empire, and later Russia would follow. This created an early division among Eastern and Western Europeans. After the Great Schism, the bishop of Rome became increasingly powerful being hereafter referred to as the pope. Although there were some conflicts with monarchs over power, most had to accept the will of the pope because so many people were devout Roman Catholics. A good example would be the debate over lay investiture in the Holy Roman Empire. Lay investiture is where the king of a country chooses the religious leaders (like bishops and priests) instead of being appointed by a religious authority. The Holy Roman Emperor, Henry IV, believed he should have the right to choose the religious leaders in the Holy Roman Empire. He quarreled with Pope Gregory VII over the issue and was threatened with excommunication. Excommunication was one of the worst things that could happen to a person at the time because they would lose all respect from others. Therefore, Henry IV had to bow to the authority of the pope which made that position even more powerful. From then on, popes were very likely to interfere in the political and personal decisions of kings throughout Europe. Pope Innocent III was perhaps the most influential of the Medieval popes, even telling some kings who to marry and who to avoid. One of the most important decisions of the Medieval popes was to spread Christianity even more throughout the Middle East and Europe. In 1095, Pope Urban II urged Christians to go and take back Jerusalem from the Muslims. For the next 200 years, there was a series of Crusades from Europe that had varying successes but most were military failures. Despite not reaching their goals, crusaders increased trade to the Middle East and brought back new ideas from the Islamic Empire that Europeans had never seen before. The Crusades also led to stronger monarchies because so many vassals of kings died as a result that there were fewer people to oppose the king. Additionally, crusaders who were unsuccessful in reclaiming Jerusalem could still spread Christianity in other places throughout Europe. For example, most of Spain was retaken from the Spanish Muslims by 1250 as a result of the Reconquista. Only Grenada, an area in the most southern part of Spain remained Muslim. Also, crusaders went out as missionaries (with swords) to the parts of Europe that had still not converted to Christianity. This was mostly in the extreme northern areas including Prussia, Poland, and the Baltic States. The Middle Ages, though not modern by our standards, started the development of many institutions that would later lead to the progressive world that we know today. The foundations of monarchies, feudalism, guilds, and the influence of the Church would have a profound influence on Europe for the next several centuries. Thus, a study of the Middle Ages provides a basis for our study of modern Europe that will begin in Chapter 2. Discussion Questions 1. What does it mean to be modern? 2. What foundations of Europe were taken from ancient Greece? 3. What foundations of Europe were taken from ancient Rome? 4. Which three empires succeeded Rome? Which was most successful and which was least successful? 5. Briefly describe how feudalism works. 6. How did feudalism lead to the rise of monarchies? 7. What were the names of some of the institutions set up to offset the power of the king? 8. How were towns different from manors? 9. What were some of the positive aspects of guilds and some of the negative aspects? 10. What were at least three consequences of the Crusades?