Learning - TeacherWeb

advertisement

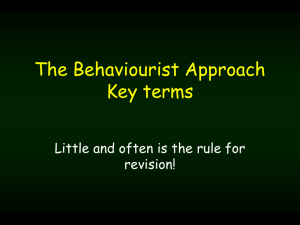

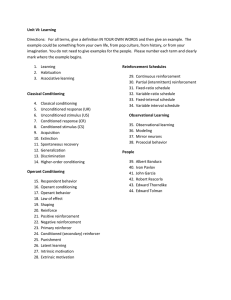

Learning Learning seems to be one process that many people take for granted but know very little about. So, how do we learn? Basically, we learn through associations. If something pleasant happens as the direct result of one of your actions, you are more likely to associate positive feelings with that action, and thus, repeat it. CLASSICAL CONDITIONING Ivan Pavlov was a Russian physiologist studying digestion. The dogs would begin to salivate when they would hear the clinking of the metal trays, or when the door would open because they came to associate that with being fed. He theorizied that they would salivate with any unrelated stimulus, if conditioned. He chose a bell. The four components of classical conditioning: Unconditioned Stimulus (US) – causes a response that is automatic, not learned. Unconditioned Response (UR) – the response to the US. Conditioned Stimulus (CS) – the originally neutral stimulus that through conditioning, gains the power to cause the response. Conditioned Response (CR) – the response to the CS. The whole object in classical conditioning is to get your subject to associate something (anything!) with the UCS. In Pavlov’s experiment, the UCS was the food and the UCR was the salivation. Pavlov took a bell, which at first meant nothing to the dogs (neutral stimulus), and after many repetitions conditioned the dogs to associate the bell with the food. Now here is the important part. Each time Pavlov gives the dog food after the bell, the bell remains a neutral stimulus. Once Pavlov rings the bell and does NOT give the food and the dogs salivate, the bell becomes what we call a conditioned stimulus (CS) and the salivation becomes a conditioned response (CR). They are called conditioned because conditioned means learned and the dogs have learned to link the bell and the food together, it is NOT unlearned or unconditional. Classical conditioning helps organisms adapt to the surrounding environment. Extinction is the procedure for reversing the learning that has taken place through classical conditioning. It occurs as the CS loses its power to trigger a CR. An extinguished response is not gone forever. Organisms sometimes display responses that were extinguished earlier. The recovered response is weaker than the original one and it can be extinguished more easily. The linking of the US and CS is called acquisition and is the goal of classical conditioning. Even after extinction, acquisition can come back at random times even years later. This is called spontaneous recovery. Generalization is when a stimuli is so close to the CS that it still causes the CR. Pavlov was not a psychologist and limited his studies to animals. It was not until American psychologist John Watson conducted his studies on a baby orphan named Albert that classical conditioning was used to actually change a human's behavior. Watson took an eleven-month-old orphan, Albert, and gave him pet white rat. Albert loved the rat and spent much of the day cuddling with it. Then Watson banged some pots loudly behind Albert while he reached for the rat. It made the baby cry. The loud noise is the US and Albert's fear is the UR. After many trials Albert began to associate the rat with the loud banging (acquisition). Then Watson would bring in the rat without the loud banging. Predictably, Albert started to cry when he saw the white rat because he associated it with the loud noises. Albert also cried when Watson brought in a white bunny or anything that resembled the rat (generalization). Because of generalization, stimuli that are similar to naturally disgusting or appealing objects will, by association, evoke some disgust or liking. (Normally desirable foods like fudge are unappealing when shaped like dog feces!!) Discrimination is the learned ability to distinguish between a conditioned stimulus and other irrelevant stimuli. (A pit bull dog racing toward you might send you into a panic, a golden retriever probably won’t.) OPERANT CONDITIONING Operant Conditioning is the concept that you can change someone’s behavior by giving them rewards or by punishing them. Unlike classical conditioning in which the learner is passive, in operant conditioning the learner plays an active part in the changes in behavior. This field was started by Edwin Thorndike. Thorndike discovered that cats learn faster if they are rewarded for their behavior. He called this idea the law of effect - if the consequences of a behavior are pleasant, the behavior will likely increase. He also stated that is the consequences of a behavior are unpleasant, the behavior will not likely increase- and he called this whole idea, instrumental learning. B.F. Skinner actually coined the term operant conditioning and started this whole school by inventing the first operant conditioning chamber, otherwise known as the Skinner Box. A Skinner box is used to train animals and usually has a way to deliver food to an animal and a lever to press or disk to peck in order to get the food. The food is called a reinforcer, and the process of giving the food is called reinforcement. A reinforcer is anything likely to increase a behavior. There are two types of reinforcement; positive and negative. A positive reinforcement strengthens a response by presenting a typically pleasurable stimulus after a response. (A good grade on your test after studying.) A negative reinforcement strengthens a response by reducing or removing an undesirable stimulus. (Pressing the snooze button stops the annoying sound of the alarm clock.) We can also change behaviors by using unpleasant consequences called punishments. It is important to realize that punishment work better to stop behaviors rather than increase them. There are two types of learning that comes from punishment: Escape learning: allows one to terminate an aversive stimulus. If you hate psychology class you will be disruptive so I will kick you out. Avoidance learning: You hate psychology class so you simply learn to skip. Whether we are talking about positive or negative reinforcement, they both fall into two main reinforcer categories: Primary reinforcer: things that are in themselves rewarding. (Food, water, rest) Secondary reinforcer: things we have learned to value such as praise, or the big one MONEY. Money can be traded in for anything and we constantly increase behaviors for money. (But if you think about it, do you really want money? No, you want what money can buy.) Reinforcement Schedules Fixed-Ratio Schedule: provides the reinforcement after a set number of responses. Variable-Ratio Schedule: provide the reinforcement after a random number of responses. Fixed-Interval Schedule: a fixed amount of time passes before the reinforcement is given. Variable- Interval Schedule: a random amount of time passes before the reinforcement is given. Variable schedules (both ratio and interval) are more resistant to extinction but also more difficult to acquire acquisition. BF Skinner used both positive and negative reinforcements (he was not really into punishments) to change the behavior of both pigeons and rats. He did it is small successive steps that he called shaping. For example, let’s say you want to teach your dog to go fetch your slippers from the closet and you wanted to use positive reinforcement to do so. You would first give your dog a treat when he goes to your closet (that may take a couple of days). Then you would reinforce him again when he picks up your slippers. Then you give him a treat once again when he brings them to your feet. The idea is that reinforcing all of these small actions is more effective than doing the whole process at once; thus you are shaping the dogs behavior. Observational learning, also known as modeling, was studied a great deal by a scientist named Albert Bandura. He believed that many of us learn through copying others. Modeling is said to have two components, observation and imitation. Bandura set up a very famous experiment called the Bobo Doll experiment to prove his idea that people observe others and try to imitate that behavior. He had children watch a video of a man pummeling and abusing a plastic clown doll named Bobo. Next, the children were led into a room with many appealing toys, but were told that they could not touch them, which made them angry and frustrated. Then, they were led into another room full of Bobo dolls which they were allowed to touch. An overwhelming 88% of kids initiated aggressive behavior towards the dolls, as they had observed the man in the video doing. Latent learning is learning that becomes obvious only once a reinforcement is given for demonstrating it. Edward Tolman studied latent learning by using rats and showing us that learning can occur but may not be immediately evident. Tolman had three groups of rats run through a maze on a series of trials. One group (Group A) got a reward each time it completed the maze, and the performance of these rats improved steadily over time. Another group of rats (Group B) never got a reward, and their performance improved only slightly over the course of the experiment. A third group of rats (Group C) was not rewarded during the first half of the experiment, but was given a reward during the second half of the experiment. Not surprisingly, during the first half of the trials, Group C was very similar to the group that never received a reward (Group B). The interesting finding, however, was that Group C's performance improved dramatically and suddenly once it began to be rewarded for finishing the maze. In fact, Group C's performance almost caught up to Group A's performance even though Group A was rewarded through the whole experiment. Tolman believed that these rats must have learned their way around the maze during the first half of the experiment, but did not improve because they had no reason to run the maze quickly. He believed that their dramatic improvement in maze-running time was due to latent learning. He suggested they made a mental representation, or cognitive map, of the maze during the first half of the experiment and displayed this knowledge once they were rewarded. Unnecessary rewards sometimes carry hidden costs, however. Excessive rewards can undermine intrinsic motivation, or the desire to perform effectively for its own sake. Extrinsic motivation is the desire to behave in certain ways to receive external rewards or avoid punishment. Rewards should be used neither to bribe, nor to control, but to signal a job well done.