File

advertisement

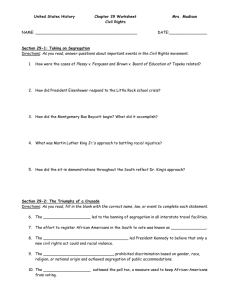

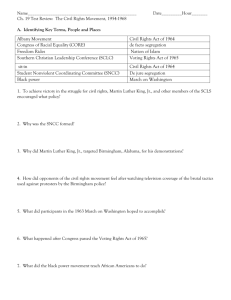

Chapter Introduction This chapter will identify the causes, main events, and effects of the civil rights movement. It examines the movement after World War II and the events that energized civil rights activists in the 1950s and 1960s. • Section 1: Early Demands for Equality • Section 2: The Movement Gains Ground • Section 3: New Successes and Challenges Objectives • Describe efforts to end segregation in the 1940s and 1950s. • Explain the importance of Brown v. Board of Education. • Describe the controversy over school desegregation in Little Rock, Arkansas. • Discuss the Montgomery bus boycott and its impact. How did African Americans challenge segregation after World War II? African Americans were still treated as secondclass citizens after World War II. Their heroic effort to attain racial equality is known as the civil rights movement. They took their battle to the street, in the form of peaceful protests, held boycotts, and turned to the courts for a legal guarantee of basic rights. DID YOU KNOW? Long before being arrested for refusing to give up her seat on a bus to a white man, Rosa Parks had protested segregation through her daily activities. She refused to drink out of the drinking fountains labeled "Colored Only." When possible, she refused to ride in segregated elevators and walked up the stairs instead. In 1896 the Supreme Court had declared segregation legal in Plessy v. Ferguson. This ruling had established a separate-but-equal doctrine, making laws segregating African Americans legal as long as equal facilities were provided. "Jim Crow" laws segregating African Americans and whites were common in the South after the Plessy v. Ferguson decision. The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) had supported court cases trying to overturn segregation since 1909. It provided financial support and lawyers to African Americans. African Americans gained political power as they migrated to Northern cities where they could vote. African Americans voted for politicians who listened to their concerns on civil rights issues, resulting in a strong Democratic Party. Despite their service in World War II, segregation at home was still the rule for African Americans. de jure segregation • in the South • separate but equal • segregation in schools, hospitals, transportation, restaurants, cemeteries, and beaches de facto segregation • • • • in the North discrimination in housing discrimination in employment only low-paying jobs were available • Discrimination in the defense industries was banned in 1941. World War II set the stage for the rise of the modern civil rights movement. • Truman desegregated the military in 1948. • Jackie Robinson became the first African American to play major league baseball. • CORE was created to end racial injustice. African American veterans were unwilling to accept discrimination at home after risking their lives overseas. In 1954, many of the nation’s school systems were segregated. The NAACP decided to challenge school segregation in the federal courts. African American attorney Thurgood Marshall led the NAACP legal team in Brown v. Board of Education. African American attorney and chief counsel for the NAACP Thurgood Marshall worked to end segregation in public schools. In 1954 several Supreme Court cases regarding segregation—including the case of Linda Brown—were combined in one ruling. The girl had been denied admission to her neighborhood school in Topeka, Kansas, because she was African American. In the Supreme Court case Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas, the Court ruled that segregation in public schools was unconstitutional and violated the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. Written by Chief Justice Earl Warren, the Brown v. Board of Education decision said: • Segregated public education violated the Fourteenth Amendment. • “Separate but equal” had no place in public education. The Brown v. Board of Education ruling was significant and controversial. In a second decision, Brown II, the courts urged implementation of the decision “with all deliberate speed” across the nation. About 100 white Southern members of Congress opposed the decision; in 1956 they endorsed “The Southern Manifesto” to lawfully oppose Brown. IN LITTLE ROCK, The Brown decision also met resistance on the ARKANSAS, WHENlevel. NINE local and state AFRICAN AMERICAN STUDENTS TRIED TO ENTER CENTRAL HIGH, THE GOVERNOR HAD THE NATIONAL GUARD STOP THEM. PRESIDENT EISENHOWER HAD TO SEND IN TROOPS TO ENFORCE THE BROWN DECISION. Elizabeth Eckford tries to enter Central High. Brown v. Board of Education convinced African Americans to challenge all forms of segregation, but it also angered many white Southerners who supported segregation. How did the NAACP and CORE challenge the Supreme Court's decision in Plessy v. Ferguson? (The NAACP supported court cases intended to overturn segregation. It provided lawyers to African Americans and helped cover the costs of their cases. CORE used sit-ins as a form of protest against segregation and discrimination. In 1943 CORE used sit-ins to protest segregation in restaurants. These sit-ins resulted in the integration of many restaurants, theaters, and other public facilities in Chicago, Detroit, Denver, and Syracuse.) When African Americans returned from World War II, they had hoped for equality. When this did not occur, the civil rights movement began as African Americans planned protests and marches to end prejudice. Some civil rights activists took direct action. In Montgomery, Alabama, Rosa Parks was arrested for refusing to give up her bus seat to a white person. This sparked a boycott to integrate public transportation. The black community walked or carpooled to work rather than take public transportation. The Montgomery bus boycott launched the modern civil rights movement. • Martin Luther King, Jr.’s inspiring speech at a boycott meeting propelled him into the leadership of the nonviolent civil rights movement. • The black community continued its bus boycott for more than a year despite threats and violence. In 1956, the Supreme Court ruled that segregated busing was unconstitutional and the boycott ended. Martin Luther King, Jr. SECTION 2 Objectives • Describe the sit-ins, freedom rides, and the actions of James Meredith in the early 1960s. • Explain how the protests at Birmingham and the March on Washington were linked to the Civil Rights Act of 1964. • Summarize the provisions of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Did You Know? In 1964 Martin Luther King, Jr., at the age of 35, was the youngest person ever to receive the Nobel Peace Prize for his work toward civil rights. How did the civil rights movement gain ground in the 1960s? Through victories in the courts and the success of sit-ins and other nonviolent protests, African Americans slowly began to win their battle for civil rights. But it was the landmark Civil Rights Act of 1964 that signaled a dramatic change in race relations by outlawing discrimination based on race, religion, or national origin. In 1960 four African Americans staged a sit-in at a Woolworth's whites-only lunch counter. This led to a mass movement for civil rights. Soon sit-ins were occurring across the nation. Students like Jesse Jackson from North Carolina Agricultural and Technical College felt that sit-ins gave them the power to change things. As sit-ins became more popular, it was necessary to choose a leader to coordinate the effort. Ella Baker, executive director of the SCLC, urged students to create their own organization. The students formed the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). Early leaders were Marion Barry and John Lewis. Robert Moses, an SNCC volunteer from New York, pointed out that most of the civil rights movement was focused on urban areas, and rural African Americans needed help as well. Student activists engaged in nonviolent civil disobedience to create change. • Students staged sit-ins. • Students formed their own organization, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), to continue to work for equal rights. Why did the sit-in movement gain attention of Americans across the nation? (Even after the demonstrators of the sit-ins were verbally and physically abused, they remained peaceful.) Students also organized freedom rides to protest segregation on the interstate transportation system. The Supreme Court had already ruled that segregation on interstate buses and waiting rooms was illegal. • Freedom riders tested the federal government’s willingness to enforce the law. • Some of the buses and riders were attacked by angry prosegregationsists. • President Kennedy intervened, ordering police and state troopers to protect the riders and mandating the desegregation of the interstate system. IN SEPTEMBER 1962, AIR FORCE VETERAN JAMES MEREDITH TRIED TO ENROLL AT THE ALL-WHITE UNIVERSITY OF MISSISSIPPI. • The federal courts ordered the school to desegregate in 1962. • Mississippi’s governor resisted, creating a stand-off between the federal government and the state government. • When Meredith arrived on campus, a riot ensued; two men were killed in the fighting. Meredith was met with the governor blocking his path. President Kennedy ordered 500 federal marshals to escort Meredith to the campus. A fullscale riot broke out with 160 marshals being wounded. The army sent in thousands of troops. For the remainder of the year, Meredith attended classes under federal guard until he graduated the following August. • Meredith graduated from the University of Mississippi in 1963. He later obtained a law degree from Columbia University. • Tragically, civil rights activist Medgar Evers, who was instrumental in helping Meredith gain admittance to “Ole Miss,” was murdered in June 1963. President Kennedy had his brother, Robert F. Kennedy of the Justice Department, actively support the civil rights movement. Robert Kennedy helped African Americans register to vote by having lawsuits filed throughout the South. In the spring of 1963, civil rights leaders focused their efforts on the South’s most segregated city— Birmingham, Alabama. • Initially, the protests were nonviolent, but they were still prohibited by the city. • City officials used police dogs and fire hoses against the protestors. • Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr., himself was arrested for violating the prohibition. When violence broke out in Montgomery Alabama, the Kennedy brothers urged the Freedom Riders to stop for a "cooling off " period. A deal was struck between Kennedy and Senator James Eastland of Mississippi. The senator stopped the violence, and Kennedy agreed not to object if the Mississippi police arrested the Freedom Riders. Martin Luther King, Jr., was frustrated with the civil rights movement. As the Cuban missile crisis escalated, foreign policy became the main priority at the White House. King agreed to hold demonstrations in Alabama, knowing they might end in violence but feeling that they were the only way to get the president's attention. King was jailed, and after his release the protests began again. The televised events were seen by the nation. Kennedy ordered his aides to prepare a civil rights bill. Why did President Kennedy not take immediate action when violence erupted against the Freedom Riders? (Kennedy was meeting with Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev, and he did not want the violence in the South to make the United States seem weak and divided.) Reaction to the Birmingham protests was overwhelming. Shocked Americans demanded that President Kennedy take action to end the violence. Calling it a “moral issue,” Kennedy proposed sweeping civil rights legislation. Civil rights leaders held a March on Washington to pressure the government to pass the President’s bill. After Alabama Governor George Wallace blocked the way for two African Americans to register for college, President Kennedy appeared on national television to announce his civil rights bill. Martin Luther King, Jr., wanted to pressure Congress to get Kennedy's civil rights bill through. On August 28, 1963, he led 200,000 demonstrators of all races to the nation's capital and staged a peaceful rally. On August 28, 1963, hundreds of thousands of people from all around the country gathered in Washington, D.C., to demonstrate. As millions more watched on television, Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr., stood before the Lincoln Memorial and delivered his unforgettable “I Have a Dream” speech. Opponents of the civil rights bill did whatever they could to slow the procedure to pass it. The bill could easily pass in the House of Representatives, but it faced difficulty in the Senate. Senators could speak for as long as they wanted while debating a bill. A filibuster occurs when a small group of senators take turns speaking and refuse to stop the debate to allow the bill to be voted on. Today a filibuster can be stopped if at least three-fifths of the Senate (60 senators) vote for cloture, a motion which cuts off debate and forces a vote. In 1960 a cloture had to be two-thirds, or 67 senators. The minority of senators opposed to the bill could easily prevent it from passing into law. In September 1963, less than three weeks after the march, a bomb exploded in the church that headquartered the SCLC in Birmingham. Four young African American girls were killed. On November 22, 1963, President Kennedy was assassinated. Vice President Lyndon B. Johnson assumed the presidency. Johnson continued to work for passage of Kennedy’s civil rights legislation. The legislation passed in the House of Representatives, but faced even more opposition in the Senate. A group of Southern Senators blocked it for 80 days using a filibuster. Supporters put together enough votes to end the filibuster. The measure finally passed in the Senate. In July, the Civil Rights Act of 1964 was signed into law. • Banned segregation in public accommodations. • Gave government the power to desegregate schools. • Outlawed discrimination in employment. • Established the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. SECTION 3 Objectives • Explain the significance of Freedom Summer, the march on Selma, and why violence erupted in some American cities in the 1960s. • Compare the goals and methods of African American leaders. • Describe the social and economic situation of African Americans by 1975. What successes and challenges faced the civil rights movement after 1964? Even after the Civil Rights Act of 1964 passed, conditions did not improve drastically for most African Americans. Impatience with the slow pace of change led to radical behavior. Riots occurred in many cities. After Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination, more civil rights legislation was passed, but new challenges also arose. The Civil Rights Act of 1964 did little to guarantee the right to vote. Many African American voters were attacked, beaten, and killed. Bombs exploded in many African American businesses and churches. Martin Luther King, Jr., decided it was time for another protest to protect African American voting rights. In 1964, many African Americans were still denied the right to vote. Southern states used literacy tests, poll taxes, and intimidation to prevent African Americans from voting. The major civil rights groups decided to end this injustice. In the summer of 1964, the SNCC enlisted 1,000 volunteers to help African Americans in the South register to vote. • Three campaign volunteers were murdered, but other volunteers were not deterred. • From this effort, the Mississippi Freedom Democratic party (MFDC) was formed as an alternative to the all-white state Democratic party. The campaign was known as Freedom Summer. A MFDP delegation traveled to the Democratic Convention in 1964 hoping to be recognized as Mississippi’s only Democratic party. MFDP member Fannie Lou Hamer testified on how she lost her home for daring to register to vote. Party officials refused to seat the MFDP, but offered a compromise: two MFDP members could be at-large delegates. Neither the MFDP nor Mississippi’s regular Democratic delegation would accept the compromise. In March 1965, Rev. King organized a march on Selma, Alabama, to pressure Congress to pass voting rights laws. Once again, the nonviolent marchers were met with a violent response. And once again, Americans were outraged by what they saw on national television. President Johnson himself went on television and called for a strong voting rights law. Sheriff Jim Clark ordered 200 state troopers and deputized citizens to rush the peaceful demonstrators. The brutal attack became known as Bloody Sunday, and the nation saw the images on television. The Voting Rights Act of 1965 was passed. • Banned literacy tests • Empowered the federal government to oversee voter registration and elections in states that discriminated against minorities • Extended to include Hispanic voters in 1975 The Voting Rights Act of 1965 gave the attorney general the right to send federal examiners to register qualified voters, bypassing the local officials who often refused to register African Americans. This resulted in 250,000 new African American voters and an increase in African American elected officials in the South. How did the passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 mark a turning point in the civil rights movement? Two goals were now achieved: to outlaw segregation and to pass federal laws to stop discrimination and protect voting rights. President Johnson also called for a federal voting rights law. The Twenty-fourth Amendment to the Constitution, which banned the poll tax, was ratified. At the same time, Supreme Court decisions were handed down that limited racial gerrymandering and established the legal principle of “one man, one vote.” The Voting Rights Act stirred growing African American participation in politics. Yet life for African Americans remained difficult. • Discrimination and poverty continued to plague Northern urban centers. • Simmering anger exploded into violence in the summer of 1967. • Watts in Los Angeles; Newark, New Jersey; and Detroit, Michigan, were the scene of violent riots. The race riot in Watts, a neighborhood in Los Angeles, lasted six days. The worst of the riots occurred in Detroit when the United States Army was forced to send in tanks and soldiers with machine guns to gain control. Johnson appointed the Kerner Commission to determine the cause of the riots. The Commission found that long-term racial discrimination was the single most important cause of violence. The commission’s findings were controversial. Because of American involvement in the Vietnam War, there was little money to spend on the commission’s proposed programs. What was the difference between African American workers and white workers by 1965? (African American workers found themselves in low-paying jobs with little chance of advancement. Some African Americans were able to get work in blue-collar factory jobs, but few advanced this far compared to whites. In 1965 only 15 percent of African Americans held professional, managerial, or clerical jobs, compared to 44 percent for whites.) By the mid-1960s, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., was criticized for his nonviolent strategy because it had failed to improve the economic condition of African Americans. As a result, he began focusing on economic issues affecting African Americans. The Chicago Movement was an effort to call attention to the deplorable housing conditions that many African Americans faced. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., and his wife moved into a slum apartment in an African American neighborhood in Chicago. Dr. King led a march through the white suburb of Marquette Park to demonstrate the need for open housing. Mayor Richard Daley had police protect the marchers, and Daley met with King to propose a new program to clean up slums. What was the result of the meeting between Mayor Richard Daley and Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.? (Daley proposed a plan to clean up the slums. Associations of realtors and bankers agreed to promote open housing. The plan was not effective.) After 1965 many African Americans began to turn away from the nonviolent teachings of Dr. King. They sought new strategies, which included self-defense and the idea that African Americans should live free from the presence of whites. Young African Americans called for black power, a term that had many different meanings. To some it meant physical selfdefense and violence. For others, including SNCC leader Stokely Carmichael, it meant they should control the social, political, and economic direction of their struggle for equality. Black power stressed pride in the African American culture and opposed cultural assimilation, or the philosophy of incorporating different racial or cultural groups into the dominant society. These ideas were popular in poor urban neighborhoods, although Dr. King and many African American leaders were critical of black power. In the mid-1960s, new African Americans leaders emerged who were less interested in nonviolent protests. One was Malcolm X, a minister in the Nation of Islam, which called for African Americans to break away from white society. Malcolm X later broke from the Nation of Islam and began to believe an integrated society was possible. In 1965 three members of the Nation of Islam shot and killed Malcolm X. He would be remembered for his view that although African Americans had been victims in the past, they did not have to allow racism to victimize them now. The Black Panthers was a militant group organized to protect blacks from police abuse. The Black Panthers— • became the symbol of young militant African Americans. • created antipoverty programs. • protested attempts to restrict their right to bear arms. Several SNCC leaders urged African Americans to use their black power to gain equality. The formation of the Black Panthers was the result of a new generation of militant African American leaders preaching black power, black nationalism, and economic selfsufficiency. The group believed that a revolution was necessary to gain equal rights. Why did the black power movement replace the nonviolent civil rights movement led by Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.? (Dr. King's nonviolent civil rights movement failed to change the poor economic conditions that many African Americans faced in the 1960s. Some African American leaders called for more aggressive forms of protest. They placed less emphasis on interracial cooperation with sympathetic whites. Many young African Americans called for black power-controlling the social, political, and economic direction of their struggle for equality. It stressed pride in the African American cultural group. It emphasized racial distinctiveness.) Although he understood their anger, King continued to advocate nonviolence. • He created a “Poor Peoples’ Campaign” to persuade the nation to do more to help the poor. • He traveled to Memphis, Tennessee, in 1968 to promote his cause and to lend support to striking sanitation workers. Martin Luther King, Jr., was assassinated on April 3, 1968, in Memphis. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., was assassinated by a sniper on April 4, 1968, creating national mourning as well as riots in more than 100 cities. By the late 1960s, the civil rights movement had made many gains. increased economic opportunities for African Americans an African American man was appointed to the Supreme Court integrated many schools and colleges eliminated legal segregation knocked down voting and political barriers banned housing discrimination The work continued into later decades. In the aftermath of King's death, Congress passed the Civil Rights Act of 1968, which contained a fair housing provision. By the late 1960s, the civil rights movement had fragmented into many competing organizations. The result was no further legislation to help African Americans. What happened to the civil rights movement after Dr. King's assassination? (Congress passed the Civil Rights Act of 1968, which contained a fair housing provision, outlawed discrimination in the sale and rental of housing, and gave the Justice Department authority to bring suits against discrimination. The civil rights movement, however, lacked the unity of purpose and vision that Dr. King had given it.)