Stephen G. CECCHETTI • Kermit L. SCHOENHOLTZ

Chapter Eighteen

Monetary Policy: Stabilizing the

Domestic Economy

McGraw-Hill/Irwin

Copyright © 2011 by The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. All rights reserved.

Introduction

• There are three interest rates:

• The federal funds rate,

• The discount rate, and

• The deposit rate.

• These are the primary tools of monetary policy

during normal times.

• In a financial crisis, central banks may also

adjust the size and composition of their balance

sheet.

18-2

Introduction

• Interest rates play a central role in all of our

lives.

• They are the cost of borrowing and the reward for

lending.

• Higher rates restrict growth of credit.

• The business press is constantly speculating

about whether the FOMC will change its target.

18-3

Introduction

• Between September 2007 and December 2008,

the FOMC lowered its target for the federal

funds rate 10 times.

• This was the first time since the 1930s that the

Fed hit the zero bound on the nominal federal

funds rate.

• Banks can always hold cash paying zero interest.

• They will never choose to lend their reserves at a

negative nominal rate.

• The nominal policy rate therefore faces a zero

bound: it will never fall below zero.

18-4

Introduction

• Even setting the federal fund rate target at

essentially zero wasn’t enough to stabilize the

economy.

• The crisis had undermined the willingness and

ability of major financial intermediaries to

lend.

• In this environment the Fed moved to

substitute itself for dysfunctional

intermediaries and markets.

• This significantly altered the Fed’s balance sheet.

18-5

18-6

Introduction

• To steady the financial system and the

economy after the crisis, the Fed utilized its

three principal conventional policy tools:

• The federal funds rate target,

• The rate for discount window lending, and

• The deposit rate.

• They did so to the fullest extent possible to

support economic activity.

18-7

Introduction

• Policymakers then proceeded to develop and

use a variety of unconventional policy tools

including:

• Commitments to keep interest rates low over time,

and

• Massive purchases of risky assets in thin, fragile

markets.

• These unconventional measures added

meaningfully to the conventional actions.

18-8

Introduction

• In this chapter we will:

• See how the Fed uses its policy tools, both conventional

and unconventional to achieve economic stability.

• See that those tools are quite similar to those of other

central banks.

• Focus on three links:

• Between the central bank’s balance sheet and its

policy tools;

• Between the policy tools and monetary policy

objectives; and

• Between monetary policy and the real economy.

18-9

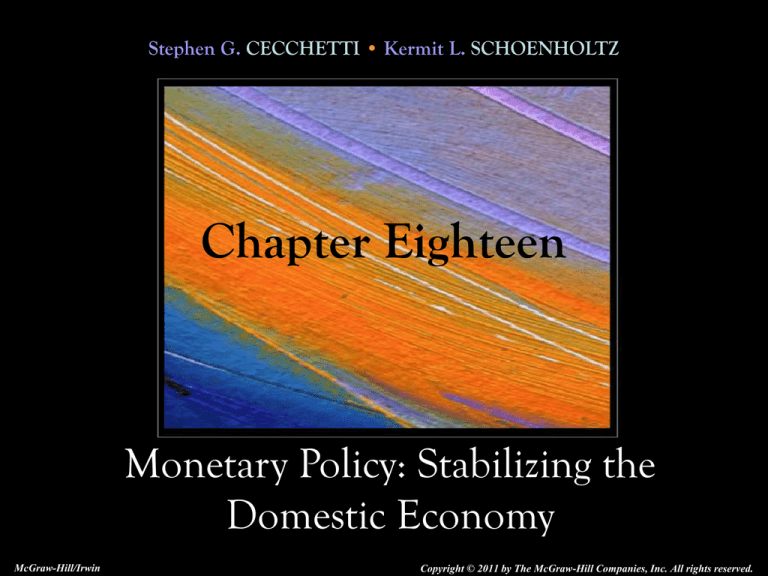

The Federal Reserve’s Conventional

Policy Toolbox

• In looking at day-to-day monetary policy, it is

essential that we understand the institutional

structure of the central bank and financial

markets.

• We will begin with the Fed and financial

markets in the U.S.

• In the next section, we will look at the ECB’s

operating procedures to see how they differ.

18-10

The Federal Reserve’s Conventional

Policy Toolbox

•

The Fed has four conventional monetary

policy tools, also known as monetary policy

instruments:

1.

2.

3.

4.

•

The target federal funds rate,

The discount rate,

The deposit rate, and

The reserve requirement.

Each of these tools are related to several of

the central bank’s functions and objectives.

18-11

The Federal Reserve’s Conventional

Policy Toolbox

18-12

The Target Federal Fund Rate and

Open Market Operations

• The target federal fund rate is the FOMC’s

primary policy instrument.

• The federal funds rate is the rate at which

banks lend reserves to each other over night.

• It is determined in the market and not controlled by

the Fed.

• We will distinguish between the target federal

funds rate set by the FOMC and the market

federal funds rate, at which transactions

between banks take place.

18-13

The Target Federal Fund Rate and

Open Market Operations

• On any given day, banks target the level of

reserves they would like to hold at the close of

business.

• That may leave them with more or less reserves

than they want.

• This gives rise to a market for reserves.

• Some banks can lend out excess reserves.

• Some banks will borrow to cover a shortfall.

18-14

The Target Federal Fund Rate and

Open Market Operations

• Without this market, banks would need to hold

substantial quantities of excess reserves as

insurance against shortfalls.

• These transactions are all bilateral agreements

between two banks.

• Loans are unsecured so the borrowing bank

must be credit worthy in the eyes of the lending

bank.

18-15

The Target Federal Fund Rate and

Open Market Operations

• If the Fed wanted to, it could force the market

federal funds rate to equal the target rate.

• However, policymakers believe that the federal

funds market provides valuable information

about the health of specific banks.

• So the Fed allows the federal funds rate to

fluctuate around its target in a channel or

corridor defined by the discount rate and the

deposit rate.

18-16

The Target Federal Fund Rate and

Open Market Operations

• When the federal fund rate climbs to the

discount rate, banks may borrow from the Fed

at the discount rate.

• When the market federal funds rate falls to the

deposit rate, banks can deposit their excess

reserves at the Fed at the deposit rate.

• The Fed can adjust the width of the so-called

channel around the target federal funds rate.

18-17

The Target Federal Fund Rate and

Open Market Operations

• The Fed targets an interest rate at the same

time that it wants to allow an interbank lending

market to flourish.

• Instead of fixing the interest rate, the Fed

controls the federal funds rate by manipulating

the quantity of reserves.

• The Fed does this by using open market

operations.

18-18

The Target Federal Fund Rate and

Open Market Operations

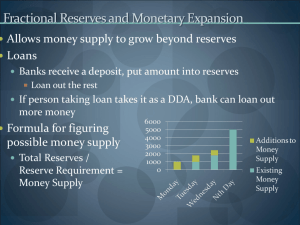

• We can use a standard supply-and-demand

graph to analyze the market in which banks

borrow and lend reserves.

• The demand curve for reserves is downward

sloping.

• However, when the federal funds rate in the

market drops to the deposit rate, banks are

willing to hold any amount of reserves supplied

beyond this level.

• So the demand curve turns flat.

18-19

The Target Federal Fund Rate and

Open Market Operations

• Keeping the market federal funds rate at the

target means balancing supply and demand for

reserves at that target rate.

• The staff of the Open Market Trading Desk

does this by:

• Estimating the demand for reserves at the target rate

each morning, and

• Supplying that quantity for the day.

• This means the daily supply for reserves is

vertical until the market federal funds rate

reaches the discount rate.

18-20

The Target Federal Fund Rate and

Open Market Operations

18-21

The Target Federal Fund Rate and

Open Market Operations

• Within a day, the federal funds rate can

fluctuate in a range from the deposit rate to the

discount rate.

• As the reserve demand shifts, the Fed staff will

use open market operations to shift the daily

reserve supply curve to accommodate the

change.

• This ensures that the market federal funds rate stays

near the target.

18-22

The Target Federal Fund Rate and

Open Market Operations

• An increase in reserve

demand is met by an open

market purchase.

• The vertical portion of

reserve supply shifts to

the left to keep the federal

funds rate at the target

level.

18-23

The Target Federal Fund Rate and

Open Market Operations

• We can compare the FOMC’s target rate with

the market rate over the last two decades.

• We can see how well the Fed’s staff has met its

objective.

• Figure 18.4 plots both the target federal funds

rate and the market federal fund rate beginning

in 1992.

18-24

The Target Federal Fund Rate and

Open Market Operations

• We can see that the market rate was close to

the target on most days after 2000.

• Changes in the reserve accounting rules in

1998 and improvements in information systems

made it easier for the Open Market Trading

Desk to estimate reserve demand.

• The use of the discount rate as a daily cap on

the funds rate after 2002 appears to have

stabilized the market rate even further.

• The 2007-2009 crisis introduced new targeting

errors.

18-25

The Target Federal Fund Rate and

Open Market Operations

18-26

• The Federal Funds Rate is the overnight

lending rate.

• Long-term interest rates = average of expected

short-term interest rates + the risk premium.

• When the expected future path of the federal

funds rate changes, long-term interest rates we

all care about change.

18-27

Discount Lending, the Lender of Last

Resort, and Crisis Management

• By controlling the quantity of loans it makes, a

central bank can control:

• The size of reserves,

• The size of the monetary base, and ultimately

• Interest rates.

• However, lending by the Federal Reserve

Banks to commercial banks, called discount

lending, is usually small aside from crisis

periods.

18-28

Discount Lending, the Lender of Last

Resort, and Crisis Management

• Yet, discount lending is the Fed’s primary tool

for:

• Ensuring short-term financial stability,

• Eliminating bank panics, and

• Preventing the sudden collapse of institutions that

are experiencing financial difficulties.

• Recall that crises were the primary impetus for

the creation of the Federal Reserve in the first

place.

18-29

Discount Lending, the Lender of Last

Resort, and Crisis Management

• The idea was that some central government

authority should be capable of providing funds

to sound banks to keep them from failing

during financial panics.

• The central bank is therefore the lender of last

resort:

• Making loans to banks when no none else will or

can.

18-30

Discount Lending, the Lender of Last

Resort, and Crisis Management

• But, a bank is supposed to show that it is sound

to get a loan in a crisis.

• This means having assets the central bank will take

as collateral.

• A bank that does not have assets it can use as

collateral for a discount loan is a bank that

should probably fail.

18-31

Discount Lending, the Lender of Last

Resort, and Crisis Management

• For most of its history, the Fed loaned reserves

to banks at a rate below the target federal fund

rate.

• Borrowing from the Fed was cheaper than

borrowing from another bank.

• But no one borrowed.

• The Fed required banks to exhaust all other sources

of funding before they applied for a loan.

18-32

Discount Lending, the Lender of Last

Resort, and Crisis Management

• Banks that used discount loans regularly faced

the possibility of being denied loans in the

future.

• These rules created quite a disincentive to

borrow from the Fed.

• By severely discouraging banks from borrowing,

the Fed destabilized the interbank market for

reserves causing some of the upward spikes in

Figure 18.4.

18-33

Discount Lending, the Lender of Last

Resort, and Crisis Management

• Because of this in 2002, officials instituted the

discount lending procedures in place today.

• The current discount lending procedures:

• Provide a mechanism for stabilizing the financial

system, and

• Help the Fed meet its interest-rate stability

objective.

18-34

Discount Lending, the Lender of Last

Resort, and Crisis Management

•

The Fed makes three types of loans:

1. Primary credit,

2. Secondary credit, and

3. Seasonal credit.

•

•

The Fed controls the interest rate on these

loans.

The banks decide how much to borrow.

18-35

Primary Credit

• Primary credit is extended on a very short-term

basis, usually overnight, to institutions that the

Fed’s bank supervisors deem to be sound.

• Banks seeking to borrow much post acceptable

collateral.

• The interest rate on primary credit is set at a

spread above the federal fund target rate called

the primary discount rate.

18-36

Primary Credit

• Primary credit is designed to provide additional

reserves at times when the open market staff’s

forecasts are off and so that the day’s reserve

supply falls short.

• The market federal funds rate will rise above the

FOMC’s target.

• Providing a facility through which banks can

borrow at a penalty rate above the target puts a

cap on the market federal funds rate.

18-37

Primary Credit

•

The system is designed both:

•

•

•

To provide liquidity in times of crisis, ensuring

financial stability, and

To keep reserve shortages from causing spikes in

the market federal funds rate.

By restricting the range over which the

market federal funds rate can move, this

system helps to maintain interest-rate

stability.

18-38

Secondary Credit

• Secondary credit is available to institutions that

are not sufficiently sound to qualify for

primary credit.

• The secondary discount rate is set about he

primary discount rate.

• There are two reason a bank might seek

secondary credit:

• A temporary shortfall of reserves, or

• They cannot borrow from anyone else.

18-39

Secondary Credit

• By borrowing in the secondary credit market, a

bank signals that it is in trouble.

• Secondary credit is for banks that are

experiencing longer-term problems that they

need some time to work out.

• Before the Fed makes the loan, it has to believe

that there is a good chance the bank will be

able to survive.

18-40

Seasonal Credit

• Seasonal credit is used primarily by small

agricultural banks in the Midwest to help in

managing the cyclical nature of farmers’ loans

and deposits.

• Historically, these banks had poor access to

national money markets.

• In recent years, however, there has been a

move to eliminate seasonal credit.

• There seems little justification for the practice

as they now have easy access to longer-term

loans from large commercial banks.

18-41

Reserve Requirements

• Since 1935, the Federal Reserve Board has had

the authority to set the reserve requirements.

• These are the minimum level of reserves banks

must hold either as vault cash or on deposit at the

Fed.

• Changes in the reserve requirement affect the

money multiplier and the quantity of money

and credit circulating in the economy.

• However, the reserve requirement turns out not

to be very useful.

18-42

Reserve Requirements

• The reserve requirement is applied to two-week

average balances in account with unlimited

checking privileges--transaction deposits.

• This period ends every second Monday.

• The reserves a bank must hold are also

averaged over a two-week period, called the

maintenance period.

• This begins on the third Thursday after the end of

the computation period.

18-43

Reserve Requirements

• This means that the banks and the Fed both

know exactly what level of reserves every bank

is required to hold during given maintenance

period well before the period starts.

• All banks have 16 days to figure out their

deposit balances before they even need to start

holding reserves.

• This procedure is called lagged-reserve

accounting, and it makes the demand for

reserves more predictable.

18-44

Reserve Requirements

• In 1980, the Monetary Control Act changed the

rules slightly so that the Fed can now set the

reserve requirement ratio between 8 and 14

percent of these transactions deposits.

• Now that interest is paid on reserves, it is not

so costly to the banks.

• To help small banks, the law specifies a

graduated reserve requirement similar to

graduated income taxes.

18-45

Reserve Requirements

• In the beginning, reserves were required to

ensure banks were sound and to reassure

depositors that they could withdraw currency

on demand.

• Today the reserve requirement exists primarily:

• To stabilize the demand for reserves, and

• To help the Fed to maintain the market federal

funds rate close to target.

18-46

Reserve Requirements

• Before August 1998, the computation and

maintenance periods overlapped.

• Banks had to manage their deposits and

reserves at the same time.

• The result was a volatile market federal funds rate.

• Since the summer of 1998, things have calmed

down quite a bit.

18-47

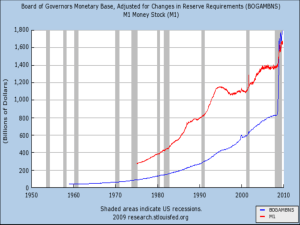

• Numerous innovations have reduced the

demand for the monetary base.

• As the demand for the reserves disappears, will

monetary policy go with it?

• There are other countries who have eliminated

reserve requirements entirely, but retain

monetary policy control.

• Australia, Canada, and New Zealand, for example.

18-48

• They do it through what is called a “channel” or

“corridor” system that involves setting not only a target

interest rate, but also a lending and deposit rate: just as

the Fed and the ECB do.

• Banks in need of funds will never be willing to pay

more than the central bank’s lending rate, and

• Those that have excess funds will never be willing to

lend at a rate below the central bank’s deposit rate.

• This will continue to give monetary policymakers a

tool to influence the economy.

18-49

18-50

Operational Policy at the European

Central Bank

• Like the Fed’s, the ECB’s monetary policy

toolbox contains:

• An overnight interbank rate,

• A rate at which the central banks lends to

commercial banks,

• A reserve deposit rate, and

• A reserve requirement.

18-51

The ECB’s Target Interest Rate and

Open Market Operations

• While the ECB occasionally engages in

outright purchases of securities, it provides

reserves to the European banking system

primarily through refinancing operations:

• A weekly auction of two-week repurchase

agreements (repo) in which ECB, through the

National Central Banks, provides reserves to banks

in exchange for securities.

• The transaction is reversed two weeks later.

18-52

The ECB’s Target Interest Rate and

Open Market Operations

• The policy instrument of the ECB’s Governing

council is the minimum interest rate allowed at

these refinancing auctions,

• Which is called the main refinancing operations

minimum bid rate.

• We will refer to this minimum bid rate as the

target refinancing rate.

18-53

The ECB’s Target Interest Rate and

Open Market Operations

• In normal times, the main refinancing

operations provide banks with virtually all their

reserves.

• However, in the crisis of 2007-2009, the ECB

sought to steady financial markets by providing

most reserves through longer-term refinancing.

18-54

The ECB’s Target Interest Rate and

Open Market Operations

•

There are some differences between the

ECB’s refinancing operations and the Fed’s

daily open market operations.

1. The operations are done at all the National Central

Banks (NCBs) simultaneously.

2. Hundreds of European banks participate in the

ECB’s weekly auctions.

3. Because of the differences in financial structure in

different countries, the collateral that is accepted

in refinancing operations differs from country to

country.

18-55

The ECB’s Target Interest Rate and

Open Market Operations

• Some of the National Central Banks in the

Eurosystem accept a broad range of collateral,

including not only government-issued bonds

but also privately issued bonds and bank loans.

• When the rating on government bonds of one

euro-area country fell below investment grade

in 2010, the ECB continued to accept them as

collateral.

18-56

The ECB’s Target Interest Rate and

Open Market Operations

• The ECB engages in both:

• Monthly long-term refinancing operations in which

is offers reserves for three months; and

• Infrequent small operations that occur between the

main refinancing operations.

18-57

The Marginal Lending Facility

• The ECB’s Marginal Lending Facility is the

analog to the Fed’s primary credit facility.

• Through this the ECB provides overnight loans

to banks at a rate that is normally well above

the target-refinancing rate.

• The spread between the marginal lending rate

and the target refinancing rate is set by the

Governing Council.

18-58

The Marginal Lending Facility

• Commercial banks initiate these borrowing

transactions when they face a reserve

deficiency that they cannot satisfy more

cheaply in the marketplace.

• Banks do borrow regularly, and on occasion

the amounts they borrow are large.

• The ECB’s system, based on the German

Bundesbanks, was the model for the 2002

redesign of the Fed’s discount window.

18-59

The Deposit Facility

• Banks with excess reserves at the end of the day can

deposit them overnight in the ECB’s Deposit Facility at

a interest rate substantially below the target-refinancing

rate.

• Again, the spread is determined by the Governing

Council.

• The existence of the deposit facility places a floor on

the interest rate that can be charged on reserves.

• The ECB’s deposit facility was the model for the Fed’s

deposit rate introduced in October 2008.

18-60

Reserve Requirements

• The ECB requires that banks hold minimum

reserves based on the level of their liabilities.

• The reserve requirement of 2% is applied to

checking accounts and some other short-term

deposits.

• Deposit level are averaged over a month, and

reserve levels must be held over the following

month.

18-61

Reserve Requirements

• The ECB pays interest on the required reserves.

• The rate:

• Is based on the interest rate from the weekly

refinancing auctions, averaged over a month,

and

• Is designed to be very close to the interbank rate.

• This means that the cost of meeting the reserve

requirement is low.

18-62

Reserve Requirements

• The European system is designed to give the

ECB tight control over the short-term money

market in the euro area.

• And it usually works well.

• The overnight cash rate is the European analog

to the market federal funds rate.

• Even during the crisis, the overnight cash rate

remained within the band formed by the

marginal lending rate and the deposit rate.

18-63

Reserve Requirements

18-64

Reserve Requirements

• This pattern contrasts starkly with that of the

U.S. market federal funds rate before 2002.

• As the Fed gradually introduced a version of

the ECB’s conventional policy toolkit, the fund

rate was more than 100 basis points away from

the target on only three occasions between

2002 and early 2010.

• The European system is clearly more

successful in keeping the short-term rate close

to target.

18-65

• The Fed officially recognizes several other

unconventional tools, or facilities, which are

described in Table 18.2.

• Note that Table 18.2 leaves out several

important mechanisms that the Fed used

extensively in the crisis.

• For example, it purchased more than $1 trillion of

mortgage-backed securities.

• The Fed also committed to keeping its policy rate

low for an extended period in order to influence

long-term interest rate expectations.

18-66

18-67

Linking Tools to Objectives:

Making Choices

• Monetary policymakers’ goals are:

•

•

•

•

Low and stable inflation,

High and stable growth,

A stable financial system, and

Stable interest and exchange rates.

• These are given to them by their elected

officials.

• But day-to-day policy is left to the technicians.

18-68

Linking Tools to Objectives:

Making Choices

•

A consensus has developed among monetary

policy experts that:

1. The reserve requirement is not useful as an

operational instrument,

2. Central bank lending is necessary to ensure

financial stability, and

3. Short-term interest rates are the tool to use to

stabilize short-term fluctuations in prices and

output.

18-69

Desirable Features of a Policy

Instrument

•

A good monetary policy instrument has three

features:

1. It is easily observable by everyone.

2. It is controllable and quickly changed.

3. It is tightly linked to the policymakers’

objectives.

18-70

Desirable Features of a Policy

Instrument

• It is important that a policy instrument be

observable to ensure transparency in

policymaking, which enhances accountability.

• An instrument that can be adjusted quickly in

the face of a sudden change in economic

conditions is clearly more useful than one that

cannot.

• And the more predictable the impact of an

instrument, the easier it will be for

policymakers to meet their objectives.

18-71

Desirable Features of a Policy

Instrument

• The reserve requirement does not meet these

criteria because banks cannot adjust their

balance sheets quickly.

• So what other options do we have?

• Well there are the other components of the central

bank’s balance sheet.

• But how do we choose between controlling

quantities and controlling prices?

18-72

Desirable Features of a Policy

Instrument

• From 1979 to 1982, the Fed targeted reserves

rather than interest rates.

• We saw interest rates that would not have been

politically acceptable if they had been announced as

targets.

• Since they said they were targeting reserves, the

Fed escaped responsibility for the high interest

rates.

• When inflation had fallen and interest rates

came back down, the FOMC reverted to

targeting the federal funds rate.

18-73

Desirable Features of a Policy

Instrument

• There is a very good reason the vast majority

of central banks in the world today choose to

target an interest rate rather than some quantity

on their balance sheet.

• With reserve supply fixed, a shift in reserve

demand changes the federal funds rate.

• If the fed chooses to target the quantity of

reserves, it gives up control of the federal funds

rate.

• Targeting reserves creates interest rate

volatility.

18-74

Desirable Features of a Policy

Instrument

• A shift in reserve demand

would move the market federal

funds rate.

• Reserve targets make interest

rates volatile.

• The federal funds rate is the

link from the financial sector to

the real economy.

• Targeting reserves could

destabilize the real economy.

18-75

Desirable Features of a Policy

Instrument

• Interest rates are the primary linkage between

the financial system and the real economy.

• Stabilizing growth means keeping interest rates

from being overly volatile.

• This means keeping unpredictable changes in

the reserve demand from influencing interest

rates and feeding into the real economy.

• The best way to do this is to target interest rates.

18-76

• Inflation targeting bypasses intermediate targets and

focuses on the final objective.

• Components:

• Public announcement of numerical target,

• Commitment to price stability as primary objective, and

• Frequent public communication.

• Inflation targeting increases policymakers’

accountability and helps to establish their credibility.

• The result is not just lower and more stable inflation

but usually higher and more stable growth as well.

18-77

Operating Instruments and

Intermediate Targets

• Central bankers sometimes use the terms

operating instrument and intermediate target.

• Operating instruments refer to actual tools of

policy.

• These are instruments that the central bank controls

directly.

• The term intermediate targets refers to

instruments that are not directly under their

control but lie somewhere between their

policymaking tools and their objectives.

18-78

Operating Instruments and

Intermediate Targets

18-79

Operating Instruments and

Intermediate Targets

• The monetary aggregates are a prime example

of intermediate targets.

• The idea behind targeting M2, for example, is

that changes in the monetary base affect the

monetary aggregates before they influence

inflation or output.

• So targeting M2, central bankers can more

effectively met their objectives.

• Money growth is just an indicator easily

monitored by the public.

18-80

Operating Instruments and

Intermediate Targets

• Central bankers have largely abandoned

intermediate targets.

• Circumstances may change in ways that make

an intermediate target unworkable.

• So while people still do discuss intermediate

targets, it is hard to justify using them.

• Policymakers instead focus on how their actions

directly affect their target objectives.

18-81

A Guide to Central Bank Interest

Rates: The Taylor Rule

• The Taylor Rule tracks the actual behavior of

the target federal funds rate and relates it to the

real interest rate, inflation, and output.

Target Fed Funds rate =

2 + Current Inflation

+ ½ (Inflation gap)

+ ½ (Output gap)

18-82

A Guide to Central Bank Interest

Rates: The Taylor Rule

• This assumes a long-term real interest rate of 2

percent.

• The inflation gap is current inflation minus an

inflation target.

• The output gap is current GDP minus its

potential level:

• The percentage deviation of current output from

potential output.

18-83

A Guide to Central Bank Interest

Rates: The Taylor Rule

• For example, if

• Inflation is currently 3 percent, and

• GDP equals its potential level so there is no output

gap, then

• The target federal funds rate should be set at 2 + 3 +

½ = 5 ½ percent.

18-84

A Guide to Central Bank Interest

Rates: The Taylor Rule

• When inflation rises above its target level,

• The response is to raise interest rates.

• When output falls below the target level,

• The response is to lower interest rates.

• If inflation is currently on target and there is no

output gap,

• The target federal funds rate should be set at its

neutral rate of target inflation plus 2.

18-85

A Guide to Central Bank Interest

Rates: The Taylor Rule

• The Taylor rule has some interesting

properties.

• The increase in current inflation feeds one for one

into the target federal funds rate; however,

• The increase in the inflation cap is halved.

• A 1 percentage point increase in the inflation

rate raises the target federal funds rate 1½

percentage points.

18-86

A Guide to Central Bank Interest

Rates: The Taylor Rule

• The Taylor rule tells us that for each

percentage point increase in inflation,

• The real interest rate, equal to the nominal interest

rate minus expected inflation, goes up half a

percentage point.

• This means that higher inflation leads

policymakers to raise the inflation-adjusted

cost of borrowing.

• This then slows the economy and ultimately reduces

inflation.

18-87

A Guide to Central Bank Interest

Rates: The Taylor Rule

• The Taylor rule also states that for each

percentage point output is above potential:

• Interest rates will go up half a percentage point.

• The halves in the equation depend on both:

• How sensitive the economy is to interest-rate

changes, and

• The preferences of central bankers.

• The more bankers care about inflation:

• The bigger the multiplier for the inflation gap, and

• The lower the multiplier for the output gap.

18-88

A Guide to Central Bank Interest

Rates: The Taylor Rule

• The implementation of the Taylor rule requires

four inputs:

•

•

•

•

The constant term, set at 2;

A measure of inflation;

A measure of the inflation gap; and

A measure of the output gap.

• The constant is a measure of the long-term

risk-free real interest rate,

• Which is about 1 percentage point below the

economy’s growth rate.

18-89

A Guide to Central Bank Interest

Rates: The Taylor Rule

• Economists and central bankers believe that the

personal consumption expenditure (PCE) index

is a more accurate measure of inflation than the

CPI.

• The PCE comes from the national income accounts.

• For the inflation target, we will follow Taylor

and use 2 percent.

• So the neutral target federal funds rate is 4 percent

(2 + 2).

18-90

A Guide to Central Bank Interest

Rates: The Taylor Rule

• For the output gap, the natural choice is the

percentage by which GDP deviates from a

measure of its trend, or potential.

• Figure 18.9 plots the FOMC’s actual target

federal funds rate, together with the rate

predicted by the Taylor rule.

• The two lines are reasonably close to each other.

• The FOMC changed the target federal funds rate

when the Taylor rule predicted it should.

18-91

A Guide to Central Bank Interest

Rates: The Taylor Rule

18-92

A Guide to Central Bank Interest

Rates: The Taylor Rule

We should recognize some caveats.

1. At times the target rate does deviate from the

Taylor rule, and with good reason.

•

•

It is too simple to take account of sudden threats to

financial stability.

The federal funds rate will be below the Taylor

rule in periods characterized by at least one of two

factors:

1. Unusually stringent conditions across an array

of financial markets; or

2. Deflationary worries that arose as nominal

interest rates approached their zero bound.

18-93

A Guide to Central Bank Interest

Rates: The Taylor Rule

2. If the economy is weak and inflation is both

low and falling below the central bank’s

objective, policymakers might set their target

rate temporarily below the one implied by the

Taylor rule.

•

•

•

This is a risk management approach to policy.

We saw this in 2002-2005 when the target federal

funds rate was below that implied by the Taylor

rule.

Some economists believe that this amplified the

housing bubble and contributed to the crisis that

followed.

18-94

A Guide to Central Bank Interest

Rates: The Taylor Rule

3. There is a lack of real time data.

•

•

While we might be able to make good monetary

policy for 1995 using the Taylor rule and the data

available to us today, that isn’t of much practical

use.

Policymakers have no choice but to make good

decisions based on information that is less than

completely accurate.

18-95

• Setting monetary policy to deliver low, stable

inflation and high stable growth is never easy.

• It was particularly challenging following the

financial crisis of 2007-2009 since the Fed had no

prior experience with many of its unconventional

policy tools.

• At the time of this article, many observers

worried that the housing market and the

economy would suffer if the FOMC were to

halt buying mortgage-backed securities.

• However, the FOMC executed its plan as

scheduled.

18-96

Unconventional Policy Tools

• Most central banks set a target for the

overnight interbank lending rate.

• However there are two circumstances when

additional policy tools can play a useful

stabilization role:

1. When lowering the target interest-rate to zero is not

sufficient to stimulate the economy; and

2. When an impaired financial system prevents

conventional interest-rate policy from supporting

the economy.

18-97

Unconventional Policy Tools

• Let’s dismiss the belief that monetary policy

becomes ineffective when the target rate is at

zero and the financial system is impaired.

• Using unconventional policies is much more

complicated than simply changing an interestrate target.

• The exit from unconventional polices can be

difficult and destabilizing.

• Therefore, they should be used only in

extraordinary situations.

18-98

Unconventional Policy Tools

•

There are three categories of unconventional

policy approaches:

1. A policy duration commitment.

•

This is when the central bank promises to keep

interest rates low in the future.

2. Quantitative easing (QE).

•

When the central bank supplies aggregate reserves

beyond the quantity needed to lower the policy

rate to zero.

18-99

Unconventional Policy Tools

3. Credit easing (CE).

•

When the central bank alters the mix of assets it

holds on its balance sheet in order to change their

relative prices in a way that stimulates economic

activity.

18-100

Policy Duration Commitment

• The simplest unconventional approach is for

the central bank to make a commitment today

about future policy target rates.

• If a policy duration commitment is stated to

last for an indefinite period, we call it an

unconditional commitment.

• Alternatively, a central bank can make a

conditional commitment to keep interest rates

low until some stated economic conditions

change.

18-101

Policy Duration Commitment

• If it works, a policy commitment will lower the

long-term interest rates that affect private

spending.

• To be effective, a policy duration commitment

needs to be credible.

• Many economists advocate policy frameworks

like inflation targeting that are designed to

enhance the credibility of a duration

commitment.

18-102

Policy Duration Commitment

• Between 2002 and 2004, the FOMC issued an

unconditional commitment indicating that its

target funds rate would stay low for the

“foreseeable future” or for a “considerable

period.”

• In 2004, it assured markets that the withdrawal

of accommodation would occur at a “measured

pace” to avoid fears of sharp rate hikes.

18-103

Policy Duration Commitment

• In 2008, the FOMC adopted a conditional

approach as the financial crisis deepened.

• They announced that “weak economic conditions

are likely to warrant exceptionally low levels of the

federal funds rate for some time.”

• Although policy duration commitments can be

effective, the Fed’s experience suggests that

they are difficult to calibrate and an have

disturbing side effects.

• They, therefore, remain tools for exceptional

circumstances.

18-104

Quantitative Easing

• QE occurs when the central bank expands the

supply of aggregate reserves beyond the level

that would be needed to maintain its policy rate

target.

• The central bank buys assets, thereby expanding its

overall balance sheet.

• Figure 18.10 illustrates the impact of QE on

supply and demand in the federal funds market.

18-105

Quantitative Easing

• At a rate of zero, banks

hold cash rather than

lend.

• The Fed can add

limitlessly to reserves

without affecting the

market federal funds

rate.

• QE is the difference

between A and B.

18-106

Quantitative Easing

• It is difficult to predict the effects of QE.

• Our limited experience means that we have

little data on which to base such a forecast.

• Moreover, the mechanism by which QE affects

economic prospects is not clear.

• An increase in the supply of reserves (QE) may

simply lead banks to hold more of them rather

than provide additional loans.

18-107

Quantitative Easing

• One mechanism is that QE can add credibility

to a policymaker’s promise to keep interest

rates low.

• Announcements of an expansion of aggregate

reserves (QE) could lower bond yields by

extending the time horizon over which

bondholders expect a zero policy rate.

• QE may reinforce the impact of a policy duration

commitment.

18-108

Quantitative Easing

• A problem with QE is that central banks do not

know now much is needed to be effective.

• QE can be powerful tool for central bankers to

prevent a sustained deflation, especially when

conventional policy tools have been exhausted.

• The first and only application since the Great

Depression occurred after the Lehman failure

in September 2008.

• Policymakers remain highly uncertain about the

appropriate dosage of QE and lack experience in

exiting from QE.

18-109

Credit Easing

• Credit easing (CE) shifts the composition of

the balance sheet away from risk-free assets

and toward risky assets.

• The central bank’s actions can influence both

the cost and availability of credit.

• In the absence of private demand for the risky

asset, the central bank’s purchase makes credit

available where none existed.

18-110

Credit Easing

• The impact of CE is likely

• To be greater in thin, illiquid markets.

• To be larger the bigger the difference between the

yield on the asset that the central bank buys and the

yield on the asset that the central bank sells.

• By altering the relative supply of such assets to

private investors, CE narrows their interest rate

differences.

18-111

Credit Easing

• In buying more than $1 trillion in MBS, the

central bank’s goal was to lower mortgage

yields and support the housing market.

• A central bank cannot reliably anticipate the

impact of CE on the cost of credit.

• In normal time a central bank typically avoids

such direct allocation of credit.

• They promote competition rather than picking

winners.

18-112

Credit Easing

• CE purposely deviates from such asset

neutrality in order to influence relative prices.

• Exiting from CE probably is also more difficult

than unwinding QE.

• Risky assets are generally harder to sell than

Treasuries.

• The central bank may not be able to get rid of them

exactly when it wants.

• Political influences can become important if the Fed

is hindered from selling specific assets for fear of

raising the costs of a particular class of borrowers.

18-113

Making an Effective Exit

• When central banks pursue conventional

interest-rate targets, officials think about the

policy choices they face every six to eight

weeks.

• It requires them to make moves today while

keeping in mind moves they may need to make far

into the future.

• The introduction of and exit from

unconventional policies also require looking in

to the future.

18-114

Making an Effective Exit

• Exiting from QE and CE poses additional

obstacles that appear technical but have

important implications.

• The question is whether a central bank that

wishes to raise interest rates will be able to do

so as quickly as desired.

• The answer depends on the size and

composition of the central bank’s balance sheet

and the toolset available.

18-115

Making an Effective Exit

• What happens with QE and CE have vastly

expanded the amount of reserves and assets on

the central bank’s balance sheet?

• The central bank may need to sell a large volume of

assets to reduce reserve supply sufficiently to raise

the policy rate target.

• But, QE and CE assets are typically more

difficult to sell.

18-116

Making an Effective Exit

• A central bank may be unable to sell assets and

withdraw reserves from the banking system

rapidly enough to hike the policy interest rate

when it desires.

• However, Central banks like the Fed have

several policy options that allow them to

tighten without having to sell their assets.

18-117

Making an Effective Exit

• Central banks can raise the deposit rate that the

central bank pays on reserves.

• Remember the deposit rate sets the floor for the

market federal fund rate.

• We can see in the supply and demand for

reserves that the demand for reserves shifts,

moving the equilibrium of the reserves from A

to B.

18-118

Making an Effective Exit

18-119

Making an Effective Exit

•

Paying interest on reserves allows a central

bank to use two powerful policy tools

independently of one another:

1. It can adjust the target rate for interbank loans

without changing the size or composition of its

balance sheet, and

2. It can adjust the size and composition of its

balance sheet without changing the target interest

rate for interbank loans.

18-120

Making an Effective Exit

• This means the central bank can change its

balance sheet in a fashion consistent with

financial stability and keep inflation under

control.

• It can avoid a fire sale by simply raising the

deposit rate that they pay on reserves.

18-121

• Economic data is revised relatively often and

the revisions can be large.

• Real GDP data is:

• Initially released at the end of a quarter,

• Revised 6 times over the next 3 years, and

• Continues to be revised after that.

• When you see a headline announcing the

publication of data on recent growth in GDP,

remember that today’s figure is just a rough

estimate.

18-122

18-123

Stephen G. CECCHETTI • Kermit L. SCHOENHOLTZ

End of

Chapter Eighteen

Monetary Policy: Stabilizing the

Domestic Economy

McGraw-Hill/Irwin

Copyright © 2011 by The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. All rights reserved.