Discussion by F. Smets

advertisement

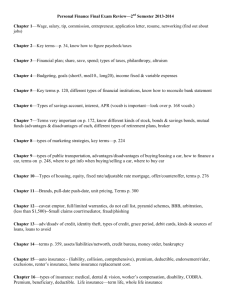

Credit frictions and optimal monetary policy Cúrdia and Woodford Discussion Frank Smets Towards an integrated macro-finance framework for monetary policy analysis Brussels, 16-17 October 2008 Summary • Nice, elegant (once you get through several pages of algebra) extension of the basic New Keynesian (NK) model; • Includes heterogeneous consumers (with different saving behaviour) which gives rise to lending and borrowing in equilibrium; • Financial intermediation is costly, giving rise to an external finance premium; possibility of financial mark-up. • As a result, the basic NK IS and Phillips curves are amended with a term (financial wedge) that acts like a cost-push shock. Policy implications • The principles of optimal monetary policy are not changed much. • The NK targeting criteria is still very much in place; identical with exogenous finance premium: • What has changed is the transmission process: financial frictions do affect how shocks and policy affect output and inflation; • However, in the benchmark calibration these effects are quite small. • So, more or less business as usual. Modification of the IS and Phillips curves • A higher wedge (lower deposit rate, higher borrowing rate) leads to more consumption by lender and less consumption by borrower. As lender consumes less, the aggregate effect on consumption is typically negative (but small). • A higher wedge leads to lower labour supply by lenders and more work by borrower. As lenders work relatively more, the lower labour supply by lenders will dominate in the aggregate (but small). Responses to a financial shock What about the role of financial frictions? What about the role of financial frictions? What about the role of financial frictions? • Two observations: – The variation in the interest rate spread is minimal in response to all aggregate shocks (only a few basis points). Is this just a calibration issue and thus solvable or a more fundamental problem? In reality, the external finance premium is much more volatile. – There is a clear positive correlation between the interest rate spread and credit. In the data the finance premium is countercyclical, there is a negative correlation.This will be difficult to solve with different calibration. Two main comments • The CW form of financial friction does not appear compatible with the countercyclical external finance premium in the data? – The premium is partly modelled as an exogenous markup and partly as covering an ad-hoc cost-function.The intermediation (monitoring) costs are a function of the amount of lending. • What financial frictions may be appropriate? – The financial sector is not explicitly modelled.There are no explicit banks that maximise profits and face asymmetric information problems, the possibility of defaults or capital adequacy constraints, … Some evidence (Christiano et al, 2008) External finance premium in the euro area – Low in booms, high in recessions Alternative financial frictions • Financial accelerator and procyclical credit worthiness: broad balance sheet effect • Bank lending channel: liquidity and capital of banks • Risk-taking channel: the attitude towards risk is procyclical. Broad balance sheet effects • Most modelling has focused on broad balance sheet effects (BGG, KM, Iacoviello, …) • Financial accelerator can lead to a countercyclical external finance premium: – Higher productivity, higher profitability, higher economic activity, higher asset prices increase the net worth of households and firms, which reduces the external finance premium, … • Pro-cyclical creditworthiness: – A booming economy implies lower risks of default, lower risk premia, higher asset prices, … and lower risk premia. Banks versus firms/households? • Normal times: limited bank lending channel; securitisation further reduces this channel. • Recently, most of the variation has been in premium paid by banks firms-euribor firms-T BILL euribor-T BILL 3 2.5 2 1.5 1 0.5 20 03 M ar 20 03 Ju n 20 03 Se p 20 03 D ec 20 04 M ar 20 04 Ju n 20 04 Se p 20 04 D ec 20 05 M ar 20 05 Ju n 20 05 Se p 20 05 D ec 20 06 M ar 20 06 Ju n 20 06 Se p 20 06 D ec 20 07 M ar 20 07 Ju n 20 07 Se p 20 07 D ec 20 08 M ar 20 08 Ju 20 n 08 Ju lA ug 0 Risk-taking channel Maddaloni, Peydró-Alcalde and Scopel (2008) Credit standards Loans to enterprises EONIA t-1 (1) 20.7 8.0 *** GDP growth t-1 Inflation t-1 Country risk t-1 (2) 20.6 9.2 *** -2.8 3.7 *** 1.7 1.1 -0.2 0.0 Loans to households for house purchase (3) (4) (5) 11.5 9.3 12.6 7.7 *** 6.5 *** 6.3 *** -5.3 -5.4 6.8 *** 5.0 *** 1.3 2.8 1.1 1.5 19.9 25.6 1.8 * 1.7 * % variable rate housing loan t-1 * EONIAt-1 % variable rate housing loan t-1 % variable rate consumer loan t-1 * EONIA t-1 # of observations # of countries (6) 8.3 4.7 *** -5.8 5.4 *** 1.8 0.9 24.3 1.6 0.1 3.0 *** 0.3 2.6 *** 276.0 12.0 276.0 12.0 276.0 12.0 Based on Bank Lending Survey data. 276.0 12.0 254.0 12.0 254.0 12.0 Different sectors respond differently • Giannoni, Lenza and Reichlin (2008): – Large BVAR with money/credit aggregates and associated interest rates • Some findings: – Credit to non-financial firms increases following a monetary policy tightening; credit to households falls. See also De Haan et al (2007). – Lending rates are sticky • Why? Credit Aggregates Loans to NFC up to 1 year Loans to NFC over 1 year 0.5 0.4 0.3 0.2 0.1 0 -0.1 -0.2 0.5 0.4 0.3 0.2 0.1 0 -0.1 -0.2 0 4 8 12 16 20 0 4 Months after the Shock 8 12 16 20 Months after the Shock Consumer Loans Loans for House Purchases 0.5 0.4 0.3 0.2 0.1 0 -0.1 -0.2 0.5 0.4 0.3 0.2 0.1 0 -0.1 -0.2 0 4 8 12 16 20 0 4 Months after the Shock Note: Dashed lines represent the 68% confidence interval. 8 12 16 Months after the Shock 20 Lending rates Lending rate, Loans to NFC up to 1 year 0.2 0.15 0.1 0.05 0 -0.05 -0.1 0 4 8 12 16 20 Months after the Shock Lending rate, Loans for House Purchases Lending rate, Consumer Loans 0.2 0.2 0.15 0.15 0.1 0.1 0.05 0.05 0 0 -0.05 -0.05 -0.1 -0.1 0 4 8 12 16 20 0 4 Months after the Shock Note: Dashed lines represent the 68% confidence interval. 8 12 16 Months after the Shock 20 Conclusions • Elegant paper • Financial frictions do not appear to be quantitatively important and do not fundamentally change the principles of monetary policy • Is likely to be model-dependent: – Other financial frictions (or shocks) are necessary to explain the procyclicality of the external finance premium; – Interaction with investment (rather than consumption) is missing.