Apartheid - White Plains Public Schools

advertisement

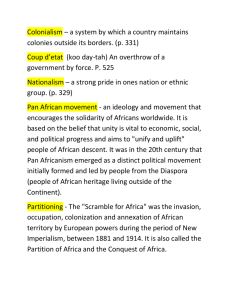

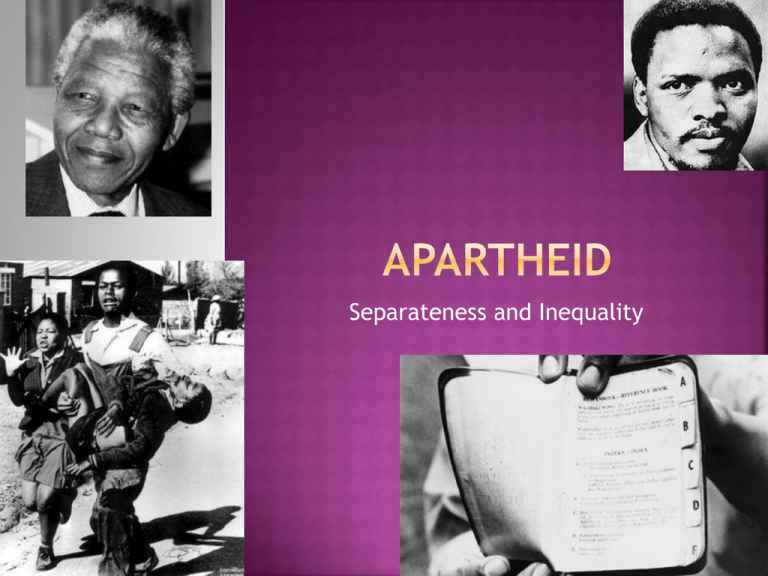

Separateness and Inequality As in Rhodesia/Zimbabwe, but for much longer, decolonization in South Africa was tainted by the clash between white and black citizens of the newly free country The government that had declared freedom from Britain was controlled by the white minority, largely descended from Dutch Boers These Afrikaners still practiced a policy of apartheid, or extreme racial segregation South Africa is one of the world’s richest sources of gold and diamonds Therefore, from the 1960s through the 1990s, the white government of South Africa turned its nation into the wealthiest, most modern, and most industrialized nation on the continent However, its system of apartheid or racial separateness made South Africa one of Africa’s most repressive nations as well By the 1980s, internal unrest, economic problems, and international revulsion were placing extreme pressure on the South African government to abandon the policy of apartheid Groups like the Zulu Confederation and the African National Congress opposed the white government The ANC’s leader, Nelson Mandela, gained the status of sympathetic dissident during his long imprisonment (1964-1990) by the white authorities His wife, Winnie Mandela, continued the struggle on his behalf Another moral figure in the anti-apartheid movement was Bishop Desmond Tutu, a black clergyman in the Anglican Church and a Nobel Peace Prize recipient In 1994, free elections resulted in the ANC’s victory and Mandela became the country’s president But to fully appreciate the profound change that South Africa experienced with the end of the apartheid era and the beginning of an era of greater equality, it is important to delve more fully into the history of the region and the development of and then resistance to the apartheid system In 1948, South Africa had a new government, the National Party Elected by a small majority in a whites-only election, its victory followed a steady increase in black migration to the country's towns This migration had led to a fear of black domination among the minority whites - the Afrikaners, and the English-speaking community, mainly of British descent Among the first measures were statutes to separate the residential areas, not only of Africans and whites, but also of mixed race people and Indians Then, racially mixed marriages were prohibited, as well as what was called “immorality” between the races (sexual relations) Apartheid, or racial separation, overshadowed South Africa for the next four decades The system's chief objective was to deny non-whites the fruits of supposedly white labors: commerce and industry Hendrick Verwoerd, South Africa's president in the 1950s and 1960s, said: " ... the white man, therefore, not only has an undoubted stake in - and right to - the land which he developed into a modern industrial state from denuded grassland and empty valleys and mountains. But - according to all the principles of morality - it was his, is his, and must remain his" Of course, many individuals saw it differently They believed that it was indeed African labor that contributed to the rise of a modern industrial state Indeed, much of the apartheid doctrine built upon an earlier history of segregation And on an assumption of supremacy among South Africa's whites that stemmed back to the first European settlers there in 1652 But apartheid was more than just a brutal power game In theory, it also had a consistent ideological base For the Afrikaners, descended from Dutch immigrants, the idea that different cultures should live apart was nothing less than God's will “The way Afrikaners justified apartheid was to say it was God-ordained," said Stanley Uys, "Most Afrikaaners are Calvinists and there is a strong streak of determinism in their makeup” It is important to remember that the first serious effort to establish a settlement in South Africa came in 1652, with the arrival of Jan van Riebeeck and several employees of the Dutch East India Company The purpose was to establish a secure fort Eventually, van Riebeeck purchased slaves to do domestic and agricultural work By the mid-18th century half the white adult males in the Cape colony own at least one slave Until 1707, the Dutch East India Company made some effort to encourage immigration to the Cape During the 18th century the colony's territory expanded more dramatically than its population, for a reason directly connected to a reliance on slaves Free burghers (similar to French bourgeoisie) came to regard manual labor as slaves' work So for many of these burghers there was no other available employment The response to this unemployment was to move away from the coast, into vast open expanses sparsely occupied by Khoikhoi and San tribes The pretext for Britain's seizing of the Cape, as the most strategic point on the important sea route to India, was the French conquest of the Netherlands in 1795 This brought the Dutch into the European war on France's side and made their attractive African colony legitimate prey While the land returned briefly to Dutch control, the Congress of Vienna left the southern tip of Africa in British hands The British and the Dutch achieved an uneasy peace That was until the discovery of gold and diamonds in the Dutch colonies of the Orange Free State and Transvaal After the Boer Wars, the British gained complete control of the land Following independence from England, an uneasy power-sharing between the British and Afrikaners held sway until the 1940's, when the Afrikaner National Party was able to gain a strong majority Strategists in the National Party invented apartheid as a means to cement their control over the economic and social system Initially, the aim of the apartheid was to maintain white domination while extending racial separation But starting in the 1960's, a plan of “Grand Apartheid” was executed, emphasizing territorial separation and police repression With the enactment of apartheid laws in 1948, racial discrimination was institutionalized In 1950, the Population Registration Act required that all South Africans be racially classified into one of three categories: white, black (African), or colored (of mixed decent) The colored category included major subgroups of Indians and Asians Classification into these categories was based on appearance, social acceptance, and descent For example, a white person was defined as “in appearance obviously a white person or generally accepted as a white person” A person could not be considered white if one of his or her parents were nonwhite The determination that a person was “obviously white” would take into account “his habits, education, and speech and deportment and demeanor‘” A black person would be of or accepted as a member of an African tribe or race, and a colored person was one that was not black or white The Department of Home Affairs (a government bureau) was responsible for the classification of the citizenry Non-compliance with the race laws were dealt with harshly All blacks were required to carry “pass books” containing fingerprints, photo and information on access to non-black areas In 1951, the Bantu Authorities Act established a basis for ethnic government in African reserves, known as “homelands” These homelands were independent states to which each African was assigned by the government according to the record of origin (which was frequently inaccurate) All political rights, including voting, held by an African were restricted to the designated homeland The idea was that black South Africans would be citizens of the homeland, losing their citizenship in South Africa and any right of involvement with the South African Parliament which held complete hegemony over the homelands From 1976 to 1981, four of these homelands were created, denationalizing nine million South Africans Thus, Africans living in the homelands needed passports to enter South Africa: aliens in their own country In 1953, the Public Safety Act and the Criminal Law Amendment Act were passed, which empowered the government to declare stringent states of emergency and increased penalties for protesting against or supporting the repeal of a law The penalties included fines, imprisonment and whippings In 1960, a large group of blacks in Sharpeville refused to carry their passes; the government declared a state of emergency The emergency lasted for 156 days, leaving 69 people dead and 187 people wounded During the states of emergency which continued intermittently until 1989, anyone could be detained without a hearing by a low-level police official for up to six months Thousands of individuals died in custody, frequently after gruesome acts of torture Those who were tried were sentenced to death, banished, or imprisoned for life, like Nelson Mandela The Sharpeville Massacre was a watershed, drawing attention to South Africa By the 1970s, the world was waking up to the reality of apartheid Mass protests and economic sanctions followed And what stung the white South Africans most of all was their virtual exclusion from world sporting competitions The Soweto riots of 1976 were the most brutal and violent riots that had taken place against the South African apartheid administration It was also amazing in how far and how fast the riot spread Its significance would go beyond the violence on the streets The police actions during the riots would be part of what instigated a world-wide boycott of South African products and signaled the increased militancy of the black population of South Africa During a reorganization of the Bantu Education Department of the government, the South African apartheid government decided to start enforcing a long-forgotten law requiring that secondary education be conducted only in Afrikaans, rather than in English or any of the native African languages This was bitterly resented by both teachers and students Many teachers themselves did not speak Afrikaans (an extremely difficult language to learn) and so could not teach the student The students resented being forced to learn the language of their oppressors and saw it as a direct attempt to cut them off from their original culture By 1976, several teachers were ignoring the directive and were fired, prompting staff resignations Tensions grew Students refused to write papers in Afrikaans and were expelled The students of one school after another went on strike The government response was to simply shut the down schools and expel the striking students A protest march was organized in the black Soweto township just outside Johannesburg on June 16,1976 Over 20,000 students turned up to the march, followed closely by the police The regular day-to-day tension between blacks and the apartheid regime’s police force was coupled now with the anger directed at the recent education act Conflict began almost immediately, as police fired round after round of tear-gas and then guns into the crowds The police showed no mercy attacked students of all ages, armed or unarmed In the book, Kaffir Boy, a young boy called David described the police’s actions on the first day of the riot: "They opened fire. They didn’t give any warning. They simply opened fire...And small children, small defenseless children, dropped down like swatted flies. This is murder, coldblooded murder" Two whites died and at least 150 blacks, mostly school children The liberation movement among blacks spread to teachers, churchmen, and others The injustice of the apartheid system increased anti-apartheid movements in the United States and Europe These anti-apartheid movements were gaining support for boycotts against South Africa, for the withdrawal of U.S. firms from South Africa and for the release of Mandela South Africa was becoming an outlaw in the world community of nations Investing in South Africa by Americans and others was coming to an end Nelson Mandela had been one of the ANC's (African National Congress) deputy presidents The ANC was an organization dedicated to the end of apartheid and greater equality for Black South Africans By the late 1950s, faced with increasing government discrimination, Mandela moved the ANC in a more radical direction Mandela was tried for treason in 1956, but acquitted after a five-year trial In 1963, Mandela and other ANC leaders were tried for plotting to overthrow the government by violence The following year Mandela was sentenced to life imprisonment He was held in Robben Island prison, off the coast of Cape Town, and later in Pollsmoor Prison on the mainland During his years in prison he became an international symbol of resistance to apartheid Mandela spent 27 years in prison In 1993, he was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize In 1994, Mandela was elected the first Black president of South Africa