Dividend Policy - McGraw Hill Higher Education

advertisement

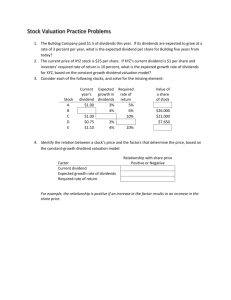

Chapter 12: Dividend and Share Repurchase Decisions Copyright 2006 McGraw-Hill Australia Pty Ltd PPTs t/a Business Finance 9e by Peirson, Brown, Easton, Howard and Pinder Prepared by Dr Buly Cardak 12–1 Learning Objectives • Define ‘dividend policy’ and understand some institutional features of dividends and share repurchases. • Explain why dividend policy is irrelevant to shareholders’ wealth in a perfect capital market with no taxes. • Outline the imputation and capital gains tax systems and explain their effects on returns to investors. Copyright 2006 McGraw-Hill Australia Pty Ltd PPTs t/a Business Finance 9e by Peirson, Brown, Easton, Howard and Pinder Prepared by Dr Buly Cardak 12–2 Learning Objectives (cont.) • Identify the factors that may cause dividend policy to be important. • Be familiar with the nature of share buybacks, dividend reinvestment plans and dividend election schemes. • Outline the main factors that influence companies’ dividend policies. Copyright 2006 McGraw-Hill Australia Pty Ltd PPTs t/a Business Finance 9e by Peirson, Brown, Easton, Howard and Pinder Prepared by Dr Buly Cardak 12–3 Dividend Policy • Business Decisions – – – • Investment Financing Dividend Dividend Policy – Determining how much of a company’s profit is to be paid to shareholders as dividends and how much is to be retained. Copyright 2006 McGraw-Hill Australia Pty Ltd PPTs t/a Business Finance 9e by Peirson, Brown, Easton, Howard and Pinder Prepared by Dr Buly Cardak 12–4 Is there an Optimal Dividend Policy? • In a perfect capital market, dividend policy has no impact on shareholders’ wealth and is, therefore, irrelevant. • Introducing capital market imperfections, the following views exist: – – – Dividend policy does not matter. A high dividend policy is best. A low dividend policy is best. Copyright 2006 McGraw-Hill Australia Pty Ltd PPTs t/a Business Finance 9e by Peirson, Brown, Easton, Howard and Pinder Prepared by Dr Buly Cardak 12–5 Institutional Features of Dividends • Dividend Declaration Procedures – Interim and final In Australia, if dividends are paid, we typically find two sorts, a final dividend is paid after the end of the accounting or reporting year. An interim dividend can be paid any time before the final report is released, usually after the half-yearly accounts are released. – Cum-dividend period – Period during which the share purchaser is qualified to receive a previously announced dividend. Ex-dividend date Shares purchased on or after the ex-dividend date do not include a right to the forthcoming dividend payment. Copyright 2006 McGraw-Hill Australia Pty Ltd PPTs t/a Business Finance 9e by Peirson, Brown, Easton, Howard and Pinder Prepared by Dr Buly Cardak 12–6 Institutional Features of Dividends (cont.) • Declaration Date – • Record (Books Closing) Date – – – • Date board of directors pass a resolution to pay a dividend. The date on which holders of record are designated to receive a dividend. This is 4 days after the ex-dividend date. The idea is that if shares are traded cum-dividend, brokers have time to notify the share register to ensure the new shareholder receives the dividend. Date of Payment – Date dividend cheques are mailed or dividends are paid electronically. Copyright 2006 McGraw-Hill Australia Pty Ltd PPTs t/a Business Finance 9e by Peirson, Brown, Easton, Howard and Pinder Prepared by Dr Buly Cardak 12–7 Institutional Features of Dividends (cont.) • Legal Considerations – – – – – – Dividends can only be paid out of profit and are not to be paid out of capital. A dividend cannot be paid if it would make the company insolvent. Dividend restrictions may exist in covenants in trust deeds and loan agreements. Franked dividend carries credits for tax paid by the company. Under imputation, if a company has the capacity to pay a franked dividend then, as a general rule, it must do so. New Zealand also operates an imputation system for dividends. Copyright 2006 McGraw-Hill Australia Pty Ltd PPTs t/a Business Finance 9e by Peirson, Brown, Easton, Howard and Pinder Prepared by Dr Buly Cardak 12–8 Institutional Features of Dividends (cont.) • Dividend Imputation – Franked dividend – Franking credit – Credit for Australian company tax paid which, when distributed to shareholders, can be offset against their tax liability. Withholding tax – Carries a credit for income tax paid by the company. Tax deducted by a company from the dividend payable to a non-resident shareholder. franking account Account that records Australian tax paid on company profits, this identifies the total amount of franking credits that can be distributed to shareholders in the form of franked dividends. Copyright 2006 McGraw-Hill Australia Pty Ltd PPTs t/a Business Finance 9e by Peirson, Brown, Easton, Howard and Pinder Prepared by Dr Buly Cardak 12–9 Repurchasing Shares • • Over the past decade, popularity of Australian companies buying back their own shares has grown as a means of returning excess capital to shareholders. Types of share buyback – – – – – Equal access buyback — pro-rata to all shareholders. Selective buyback — repurchase from specific, limited number of shareholders. On-market buyback — repurchase through normal stock exchange trading. Employee share scheme buyback. Minimum loading buyback — buy back small parcels of shares (transaction costs). Copyright 2006 McGraw-Hill Australia Pty Ltd PPTs t/a Business Finance 9e by Peirson, Brown, Easton, Howard and Pinder Prepared by Dr Buly Cardak 12–10 Dividend Policies • Residual dividend policy – • Pay out as dividends any profit that management does not believe can be invested profitably. Smoothed dividend policy – – Target proportion of annual profits to be paid out as dividend. Aim for dividends to equal the long-run difference between expected profits and expected investment needs. Constant payout policy. Copyright 2006 McGraw-Hill Australia Pty Ltd PPTs t/a Business Finance 9e by Peirson, Brown, Easton, Howard and Pinder Prepared by Dr Buly Cardak 12–11 Managers and Dividend Decisions • Dividends are an ‘active decision variable’ (Lintner). • Lintner found: – – – – Companies have a long-term target payout ratio. Managers focus on change in payout. Dividends are smoothed relative to profits. Managers avoid changes in dividends that may have to be subsequently reversed. Copyright 2006 McGraw-Hill Australia Pty Ltd PPTs t/a Business Finance 9e by Peirson, Brown, Easton, Howard and Pinder Prepared by Dr Buly Cardak 12–12 Irrelevance Theory • Value of firm is determined solely by the earning power of the firm’s assets, and the manner in which the earnings stream is split between dividends and retained earnings does not affect shareholders’ wealth. Copyright 2006 McGraw-Hill Australia Pty Ltd PPTs t/a Business Finance 9e by Peirson, Brown, Easton, Howard and Pinder Prepared by Dr Buly Cardak 12–13 Modigliani and Miller (1961) • Given the investment decision of the firm, the dividend payout ratio is a mere detail. It does not affect the wealth of shareholders. • Assumptions – – – No taxes, transaction costs, or other market imperfections. A fixed investment or capital budgeting program. No personal taxes — investors are indifferent between receiving dividends or capital gains. Copyright 2006 McGraw-Hill Australia Pty Ltd PPTs t/a Business Finance 9e by Peirson, Brown, Easton, Howard and Pinder Prepared by Dr Buly Cardak 12–14 MM’s Conclusion • Dividend policy is a trade-off between retaining profit, paying dividends and making new share issues to replace cash paid out. • Paying a dividend and issuing new shares to replace the cash: – – Does not change the value of the company; and Does not change the wealth of the old shareholders, because the value of their shares falls by an amount equal to the cash paid to them. Copyright 2006 McGraw-Hill Australia Pty Ltd PPTs t/a Business Finance 9e by Peirson, Brown, Easton, Howard and Pinder Prepared by Dr Buly Cardak 12–15 MM’s Conclusion (cont.) • If a company increases its dividends, it must replace the cash by making a share issue. • Old shareholders receive a higher current dividend, but a proportion of future dividends must be diverted to the new shareholders. • The present value of these forgone future payments is equal to the increase in current dividends. Copyright 2006 McGraw-Hill Australia Pty Ltd PPTs t/a Business Finance 9e by Peirson, Brown, Easton, Howard and Pinder Prepared by Dr Buly Cardak 12–16 MM’s Conclusion (cont.) • The MM dividend irrelevance proposition is valid in a perfect capital market with no taxes. • Therefore, if dividend policy is important in practice, the reasons for its importance must relate to factors that MM excluded from their analysis. Copyright 2006 McGraw-Hill Australia Pty Ltd PPTs t/a Business Finance 9e by Peirson, Brown, Easton, Howard and Pinder Prepared by Dr Buly Cardak 12–17 Dividends and Taxes • Differential tax treatment of dividend income versus capital gains arising from retained profits can either favour or penalise payment of dividends. • This difference in tax treatment is understood by comparing a classical tax system with an imputation tax system. Copyright 2006 McGraw-Hill Australia Pty Ltd PPTs t/a Business Finance 9e by Peirson, Brown, Easton, Howard and Pinder Prepared by Dr Buly Cardak 12–18 Classical Tax System • In a classical tax system: – – – – • Company profits are taxed at the corporate tax rate, tc, leaving (1– tc) to be distributed as a dividend. Dividends received by shareholders are then taxed at the shareholder’s personal marginal tax rate, tp. The consequence is that, from a dollar of company profit, the shareholder ends up with (1– tc)x (1– tp) dollars of after-tax dividend in a classical tax system. The result is that profit paid as a dividend is effectively taxed twice. In Australia, a classical tax system operated until 1 July 1987, when an imputation system was introduced. Copyright 2006 McGraw-Hill Australia Pty Ltd PPTs t/a Business Finance 9e by Peirson, Brown, Easton, Howard and Pinder Prepared by Dr Buly Cardak 12–19 Imputation Tax System • A system under which Australian resident equity investors can use tax credits associated with franked dividends to offset their personal tax. • The system eliminates the double taxation inherent in the classical tax system. • Company tax is assessed on the corporate profits in the normal way, at the corporate tax rate (tc). • As of 2002, tc is 30%. Copyright 2006 McGraw-Hill Australia Pty Ltd PPTs t/a Business Finance 9e by Peirson, Brown, Easton, Howard and Pinder Prepared by Dr Buly Cardak 12–20 Imputation Tax System (cont.) • For each dollar of franked dividends paid by the company, resident shareholders will be taxed at their marginal rate (tp) on an imputed dividend of $D / (1 – tc). • This is referred to as the ‘grossed-up dividend’. • The grossed-up dividend is equal to the dividend plus the franking credit. • Franking credit is given by: Imputation dividend tc credit 1 tc Copyright 2006 McGraw-Hill Australia Pty Ltd PPTs t/a Business Finance 9e by Peirson, Brown, Easton, Howard and Pinder Prepared by Dr Buly Cardak 12–21 Imputation Tax System (cont.) • The shareholder receives a tax credit equal to the franking credit. • The credit can be used to offset tax liabilities associated with any other form of income. • The tax credit cannot be carried forward but excess or unused tax credits are refunded as of July 2000. Copyright 2006 McGraw-Hill Australia Pty Ltd PPTs t/a Business Finance 9e by Peirson, Brown, Easton, Howard and Pinder Prepared by Dr Buly Cardak 12–22 Imputation Tax System (cont.) • The result is that franked dividends are effectively tax-free to Australian residents, if the investor’s marginal tax rate is equal to the corporate tax rate. • If the investor’s marginal tax rate is less than the corporate rate, then the investor will have excess tax credits which can be used to reduce tax on other income, or refunded if they cannot be used. Copyright 2006 McGraw-Hill Australia Pty Ltd PPTs t/a Business Finance 9e by Peirson, Brown, Easton, Howard and Pinder Prepared by Dr Buly Cardak 12–23 Imputation Tax System (cont.) • If the investor’s marginal tax rate is greater than the corporate rate, some tax will be payable by the investor on the dividend. • Investors pay tax, at their marginal rate, on any unfranked dividends received. • Since 1 October 2003, Australian and New Zealand companies have been able to distribute all franking credits to Australian and NZ resident shareholders. Copyright 2006 McGraw-Hill Australia Pty Ltd PPTs t/a Business Finance 9e by Peirson, Brown, Easton, Howard and Pinder Prepared by Dr Buly Cardak 12–24 Imputation and Capital Gains Tax • If companies retain profits, their share price is likely to rise relative to companies that distribute profits, giving rise to capital gains tax liabilities for shareholders if and when the shares are sold. • Capital gains receive preferential tax treatment compared to ‘ordinary’ income. • Capital gains tax (CGT) applies only to short-term gains and to long-term real capital gains on assets acquired on or after 20 September 1985, and is payable only when gains have been realised. Copyright 2006 McGraw-Hill Australia Pty Ltd PPTs t/a Business Finance 9e by Peirson, Brown, Easton, Howard and Pinder Prepared by Dr Buly Cardak 12–25 Imputation and Capital Gains Tax (cont.) • As of 21 September 1999, capital gains earned over 12 months or longer are subject to CGT discounting. • For individuals, only 50% of the gain is taxed at their personal marginal tax rate. • For superannuation funds, the discount is 33.33%, so 66.66% of the capital gain is subject to CGT. Copyright 2006 McGraw-Hill Australia Pty Ltd PPTs t/a Business Finance 9e by Peirson, Brown, Easton, Howard and Pinder Prepared by Dr Buly Cardak 12–26 Imputation and Capital Gains Tax (cont.) • Consequently, effective rates of CGT are likely to be relatively low for many investors. • However, where a capital gain arises from retention of profits which have been taxed, any CGT that is payable will be in addition to the tax already paid by the company. • In other words, retention of profits can involve double taxation as franking credits cannot be transferred to shareholders through capital gains. Copyright 2006 McGraw-Hill Australia Pty Ltd PPTs t/a Business Finance 9e by Peirson, Brown, Easton, Howard and Pinder Prepared by Dr Buly Cardak 12–27 Imputation and Dividend Policy • If all company shares were held by resident investors with marginal tax rates less than company tax rates, then the optimal dividend policy for an Australian company is one that at least pays dividends to the limit of its franking account balance. Copyright 2006 McGraw-Hill Australia Pty Ltd PPTs t/a Business Finance 9e by Peirson, Brown, Easton, Howard and Pinder Prepared by Dr Buly Cardak 12–28 Imputation and Dividend Policy (cont.) • This policy will benefit resident investors in two ways: – – • The franking credits attached to franked dividends can be used to reduce investors’ personal tax liabilities. Since the alternative to dividends is capital gains, which are subject to company tax and CGT, higher dividends will mean that less CGT is payable by investors. If all franking credits are not paid out, the credits that are retained are potentially wasted as they have no value except when accompanying dividend payments. (At best, their value is discounted if they are used to offer franking credits on future dividends.) Copyright 2006 McGraw-Hill Australia Pty Ltd PPTs t/a Business Finance 9e by Peirson, Brown, Easton, Howard and Pinder Prepared by Dr Buly Cardak 12–29 Imputation and Dividend Policy (cont.) • Complicating factors for optimal dividend policy: – – – • Shares are held by both resident and non-resident individuals. Many individuals have personal marginal tax rates that are greater than the company tax rate and may have a taxbased preference for retention of profits. Since July 2000, resident investors that are tax-exempt have excess franking credits refunded. Overall, the interaction of CGT and the imputation system means that shareholders with low (high) marginal tax rates prefer profits to be paid out as dividends (retained, leading to capital gains). Copyright 2006 McGraw-Hill Australia Pty Ltd PPTs t/a Business Finance 9e by Peirson, Brown, Easton, Howard and Pinder Prepared by Dr Buly Cardak 12–30 Imputation Clienteles • Clientele effect – – – – Investors choosing to invest in companies that have policies meeting their particular requirements. For example: Investors who require high current income may choose to invest in companies that have high dividend payouts. Also, companies paying fully-franked dividends would attract shareholders who receive the greatest value from tax credits (i.e. Australian residents, possibly with low personal tax rates who can receive a refund of franking credits). Copyright 2006 McGraw-Hill Australia Pty Ltd PPTs t/a Business Finance 9e by Peirson, Brown, Easton, Howard and Pinder Prepared by Dr Buly Cardak 12–31 Value of Franking Credits • The argument that investors will prefer tax credits to be distributed rather than retained assumes that tax credits are valuable to investors. • Supporting evidence from the dividend drop-off ratio: – ‘Drop-off ratio’: ratio of the decline in the share price on the ex-dividend day to the dividend per share. Copyright 2006 McGraw-Hill Australia Pty Ltd PPTs t/a Business Finance 9e by Peirson, Brown, Easton, Howard and Pinder Prepared by Dr Buly Cardak 12–32 Value of Franking Credits (cont.) • Walker and Partington (1999) study drop-off ratios: – – – 1 January 1995 – 1 March 1997, when ASX allowed trading in cum-dividend shares after the ex-dividend date. Find a drop-off ratio of 1.23, implying that $1 of fully-franked dividends is worth more than $1. Some variability because of different individual marginal tax rates. Copyright 2006 McGraw-Hill Australia Pty Ltd PPTs t/a Business Finance 9e by Peirson, Brown, Easton, Howard and Pinder Prepared by Dr Buly Cardak 12–33 Value of Franking Credits (cont.) • Cannavan, Finn and Gray (2004) also study drop-off ratios: – – – Use futures contracts on dividend paying shares to compare with actual shares. Futures contract does not entitle holder to dividends so difference should reflect market value of dividend and associated franking credit. Tax rules change requiring shares to be held 45 days in order to claim franking credits. Prior to introduction of this rule, franking credits had some value — franking credits were easily transferable from those that could not use them to those that could. After this rule, franking credits appear to be worthless. Copyright 2006 McGraw-Hill Australia Pty Ltd PPTs t/a Business Finance 9e by Peirson, Brown, Easton, Howard and Pinder Prepared by Dr Buly Cardak 12–34 Non-Tax Reasons for the Relevance of Dividend Policy • Information effects and signalling to investors: – – Evidence suggests share price changes around the time of the announcement of dividend changes are positively related to the change in the dividend. MM claim that this does not invalidate irrelevance theory. The price change is the result of the information content associated with the dividend announcement. Copyright 2006 McGraw-Hill Australia Pty Ltd PPTs t/a Business Finance 9e by Peirson, Brown, Easton, Howard and Pinder Prepared by Dr Buly Cardak 12–35 Non-Tax Reasons for the Relevance of Dividend Policy (cont.) • Three implications of dividend information and signalling hypothesis: – – – – Unanticipated dividend changes should be followed by share price changes in the same direction. Empirical support for this implication found in US studies by Grullon, Michaely and Swaminathan (2002), Michaely, Thaler and Womack (1995), and Healy and Palepu (1988). Australian evidence supports this implication as well: Balachandaran and Faff (2004). Special dividend announcements provide mean abnormal returns of 5.44% over a 3-day period. Copyright 2006 McGraw-Hill Australia Pty Ltd PPTs t/a Business Finance 9e by Peirson, Brown, Easton, Howard and Pinder Prepared by Dr Buly Cardak 12–36 Non-Tax Reasons for the Relevance of Dividend Policy (cont.) • Three implications of dividend information and signalling hypothesis (cont.): – – – – Unanticipated dividend changes should be followed by market revision of expectations of future earnings in the same direction. Empirical evidence also supports this implication, for example Ofer and Seigel (1987). Analysts revisions of earnings forecasts are positively related to dividend changes. Grullon and Michaely (2004) find that analysts revise profit forecasts downwards during the month of a share repurchase announcement. Copyright 2006 McGraw-Hill Australia Pty Ltd PPTs t/a Business Finance 9e by Peirson, Brown, Easton, Howard and Pinder Prepared by Dr Buly Cardak 12–37 Non-Tax Reasons for the Relevance of Dividend Policy (cont.) • Three implications of dividend information and signalling hypothesis (cont.): – – – – – Changes in dividends should be followed by changes in earnings in the same direction. Evidence on this implication is mixed and does not strongly support it. Watts (1973) and Penman (1983) find little support for implication. Healy and Palepu (1988) find support when focusing on companies that initiate and omit dividends. Benartzi, Michaely and Thaler (1997), and Grullon, Michaely and Swaminathan (2002) find link between increased dividends and recent earnings but no link between increased dividends and future increases in earnings. Copyright 2006 McGraw-Hill Australia Pty Ltd PPTs t/a Business Finance 9e by Peirson, Brown, Easton, Howard and Pinder Prepared by Dr Buly Cardak 12–38 Non-Tax Reasons for the Relevance of Dividend Policy (cont.) • Three implications of dividend information and signalling hypothesis (cont.): – – – Changes in dividends should be followed by changes in earnings in the same direction. De Angelo, De Angelo and Skinner (1996) also find no link between dividend increases and future positive profit surprises. Signalling argument, the third implication, is not supported by empirical evidence. • Signal is not of continued dividend growth but rather of permanence of current increase in dividend. • Alternatively, increased dividend may signal reduced risk associated with profits and cash flows, thereby reducing discount rate and raising share price. Copyright 2006 McGraw-Hill Australia Pty Ltd PPTs t/a Business Finance 9e by Peirson, Brown, Easton, Howard and Pinder Prepared by Dr Buly Cardak 12–39 Non-Tax Reasons for the Relevance of Dividend Policy (cont.) • Three implications of dividend information and signalling hypothesis (cont.): – – – Alternative interpretations of information conveyed. Benartzi, Michaely and Thaler (1997) argue that the signal is not of continued dividend growth but of permanence of current increase in dividend. Alternatively, Grullon, Michaely and Swaminathan (2002) argue that an increased dividend may signal reduced risk associated with profits and cash flows, thereby reducing discount rate and raising share price. Copyright 2006 McGraw-Hill Australia Pty Ltd PPTs t/a Business Finance 9e by Peirson, Brown, Easton, Howard and Pinder Prepared by Dr Buly Cardak 12–40 Non-Tax Reasons for the Relevance of Dividend Policy (cont.) • Agency costs and corporate governance – – Agency costs can be reduced by paying higher dividends. Increased capital-raising required: Accountability to market. Increases provision of information. Increases monitoring of managers. Managers more likely to act in interests of shareholders. Copyright 2006 McGraw-Hill Australia Pty Ltd PPTs t/a Business Finance 9e by Peirson, Brown, Easton, Howard and Pinder Prepared by Dr Buly Cardak 12–41 Non-Tax Reasons for the Relevance of Dividend Policy (cont.) • Agency costs and corporate governance (cont.) – – – Lie (2000) and Grullon, Michaely and Swaminathan (2002) provide empirical evidence that increased payouts either as special dividends, increased ordinary dividends or a share repurchase program signal reduced opportunity to over invest, free cash flow hypothesis. Firms with limited investment opportunities exhibit a bigger abnormal return to the announcement of such initiatives. In Australia, Telstra’s announcement in June 2004 that they intend to focus on a higher dividend payout rate of 80% and to initiate $1.5b worth of capital management programs (special dividends and / or repurchases) was greeted with a 4.6% increase in share price. Copyright 2006 McGraw-Hill Australia Pty Ltd PPTs t/a Business Finance 9e by Peirson, Brown, Easton, Howard and Pinder Prepared by Dr Buly Cardak 12–42 Non-Tax Reasons for the Relevance of Dividend Policy (cont.) • Agency costs and corporate governance (cont.) – – – La Porta, Lopez-De-Silanes, Shleifer and Vishny (2000) provide empirical evidence that in countries where investors’ interests are relatively well protected, dividends are less likely to be a mechanism to reduce agency costs. Well-protected investors are willing to forgo dividends now in return for growth. High-growth companies pay lower dividends in economies where investors are relatively well-protected legally. Copyright 2006 McGraw-Hill Australia Pty Ltd PPTs t/a Business Finance 9e by Peirson, Brown, Easton, Howard and Pinder Prepared by Dr Buly Cardak 12–43 Non-Tax Reasons for the Relevance of Dividend Policy (cont.) • Agency costs and corporate governance (cont.) – – – – Correia Da Silva, Goeregen and Renneboog (2004) argue that dividend policy may be influenced by corporate governance regimes. Market based and block-holder based regimes of corporate governance. The presence of large (block) shareholders reduces the impetus to pay out dividends (consider News Corp. in Australia, large block holder, low dividends). Controlling interest is a substitute for dividends as a monitoring mechanism, while agency costs are less of an issue as shareholder is potentially insider or even a manager. Copyright 2006 McGraw-Hill Australia Pty Ltd PPTs t/a Business Finance 9e by Peirson, Brown, Easton, Howard and Pinder Prepared by Dr Buly Cardak 12–44 Non-Tax Reasons for the Relevance of Dividend Policy (cont.) • Investment opportunities – Differences in the nature of investment opportunities will influence corporate financial decisions, including dividends. – Lots of investment opportunities — low dividends. – Jones and Sharma (2001) rank Australian companies on basis of growth opportunities between 1991 and 1998. – Find low-growth companies have lower dividend yields than high-growth companies. Copyright 2006 McGraw-Hill Australia Pty Ltd PPTs t/a Business Finance 9e by Peirson, Brown, Easton, Howard and Pinder Prepared by Dr Buly Cardak 12–45 Non-Tax Reasons for the Relevance of Dividend Policy (cont.) • • Shareholders’ preference for current income – Need for shares to yield current income. – MM support irrelevance stance, given shareholders can create ‘homemade dividends’. Issue and transaction costs – Company can avoid incurring costs associated with share issue by reducing dividends. – This means that more financing requirements can be met internally, out of retained profits. Copyright 2006 McGraw-Hill Australia Pty Ltd PPTs t/a Business Finance 9e by Peirson, Brown, Easton, Howard and Pinder Prepared by Dr Buly Cardak 12–46 Non-Tax Reasons for the Relevance of Dividend Policy (cont.) • Dividend clienteles – Groups of investors who choose to invest in companies that have dividend policies which meet their particular requirements. – If equilibrium exists in terms of the supply and demand for particular dividend policies, the price of a company’s shares will be independent of its dividend policy. – This is because there are always other companies with the same (or a similar) dividend policy that can act as substitutes. Copyright 2006 McGraw-Hill Australia Pty Ltd PPTs t/a Business Finance 9e by Peirson, Brown, Easton, Howard and Pinder Prepared by Dr Buly Cardak 12–47 Share Repurchases • A share buyback is when a company purchases its own shares on the stock market and then proceeds to either cancel them (Aust.) or retain them as treasury stock (US). • There are legal requirements associated with buybacks, but generally companies can repurchase up to 10% of their ordinary shares in a 12-month period. • Rapid growth in repurchases in Australia, $770m in the 1995 financial year, up to $7.7b in the 12 months to June 2004. • In 1999 and 2000, US industrial companies distributed more cash to shareholders through share repurchases than dividends. Copyright 2006 McGraw-Hill Australia Pty Ltd PPTs t/a Business Finance 9e by Peirson, Brown, Easton, Howard and Pinder Prepared by Dr Buly Cardak 12–48 Why Repurchase Shares? • Dividend substitution – – • If capital gains are taxed more favourably than dividends. Some supporting evidence from the US, where dividend payout ratios have been falling in the 1980s and 1990s. Improved performance measures – – EPS may rise, but if cash is returned rather than used to retire debt, financial risk is increased and PE ratio along with share price may fall. Return of funds that cannot be profitably used will raise share price. Copyright 2006 McGraw-Hill Australia Pty Ltd PPTs t/a Business Finance 9e by Peirson, Brown, Easton, Howard and Pinder Prepared by Dr Buly Cardak 12–49 Why Repurchase Shares? (cont.) • Signalling and undervaluation – – • Managers buying back company stock indicates that they believe the stock is undervalued by the market. Alternatively, a buyback announcement could be accompanied by some new information, e.g. sale of unprofitable asset/division. Resource allocation and agency costs – – Share repurchase returns capital to shareholders, who can reallocate funds into profitable activities through the capital market. Reduces the potential for managers to inefficiently use free cash (i.e. reduces agency costs). Copyright 2006 McGraw-Hill Australia Pty Ltd PPTs t/a Business Finance 9e by Peirson, Brown, Easton, Howard and Pinder Prepared by Dr Buly Cardak 12–50 Why Repurchase Shares? (cont.) • Financial flexibility – – • Payment of dividends is a long-term commitment and sudden major changes (especially decreases) in dividend policy are unappreciated by market. buybacks offer an alternative way to make distributions that may not be permanent. Employee share options – – Unlike paying dividends, share repurchases do not lead to the ex-dividend price drop-off. Option holders (typically management) prefer a share repurchase to a dividend payout as a means of distributing profits to shareholders. Copyright 2006 McGraw-Hill Australia Pty Ltd PPTs t/a Business Finance 9e by Peirson, Brown, Easton, Howard and Pinder Prepared by Dr Buly Cardak 12–51 Share Repurchases in Australia • Five categories of share buyback: – – – – – Equal access buyback — pro-rata to all shareholders. Selective buyback — repurchase from specific, limited number of shareholders. On-market buyback — repurchase through normal stock exchange trading. Employee share scheme buyback. Minimum holding buyback — buy back small parcels of shares (transaction costs). Copyright 2006 McGraw-Hill Australia Pty Ltd PPTs t/a Business Finance 9e by Peirson, Brown, Easton, Howard and Pinder Prepared by Dr Buly Cardak 12–52 Share Repurchases in Australia • Off-market buybacks can be structured to provide significant tax advantages with a large dividend and franking component. (see for example Finance in Action: CBA’s 2004 off-market share buyback.) • Key point is that receipt of such a dividend is at the discretion of the shareholder who sells the shares back to the company. • ASX requires companies to justify buyback — many on-market buybacks are justified on the basis that the market undervalues the company’s shares. • Otchere and Ross (2002) find positive abnormal returns for companies, citing undervaluation as justification of a buyback. Copyright 2006 McGraw-Hill Australia Pty Ltd PPTs t/a Business Finance 9e by Peirson, Brown, Easton, Howard and Pinder Prepared by Dr Buly Cardak 12–53 Dividend Reinvestment Plans (DRPs) • Definition – DRPs offer shareholders the option to apply all or part of their cash dividends to the purchase of additional shares in the company (in some cases at a discount price). – The number of listed companies which operate dividend reinvestment plans increased from just 5 in late 1982 to 14% of all listed companies by 1999. – In 2003/04, $5.2b of total $29.8b of dividends declared by listed companies were reinvested through DRPs. – The imputation system has played a large part in this increased popularity, providing an incentive to increase payouts. Copyright 2006 McGraw-Hill Australia Pty Ltd PPTs t/a Business Finance 9e by Peirson, Brown, Easton, Howard and Pinder Prepared by Dr Buly Cardak 12–54 DRPs (cont.) • Benefits to the company: – – • Cheap and effective means of raising capital and conserving cash Promotes good shareholder relations and stability of ownership Disadvantages to the company: – – – – Administration costs Promotion of the plan Excessive capital raising Dilution of EPS Copyright 2006 McGraw-Hill Australia Pty Ltd PPTs t/a Business Finance 9e by Peirson, Brown, Easton, Howard and Pinder Prepared by Dr Buly Cardak 12–55 DRPs (cont.) • Benefits to investors: – Taxation benefits. – Flexibility. – Savings program. – Shares are generally issued at a discount to market price and are free from brokerage and stamp duty. • Disadvantages to investors: – Need to keep substantive and comprehensive records throughout the period of ownership of assets affected by capital gains tax. – Familiarisation with plan and its tax consequences. – No control over the reinvestment price. – Discount disadvantages shareholders who do not participate in the DRP. Copyright 2006 McGraw-Hill Australia Pty Ltd PPTs t/a Business Finance 9e by Peirson, Brown, Easton, Howard and Pinder Prepared by Dr Buly Cardak 12–56 Dividend Election Schemes • Allow shareholders the option of receiving their dividends in one or more of a number of forms. • For example, as bonus shares (deferring tax), or as dividends from overseas subsidiaries (foreign tax credits). • • Tax effectiveness of ‘dividend streaming’ via such schemes has been restricted. Copyright 2006 McGraw-Hill Australia Pty Ltd PPTs t/a Business Finance 9e by Peirson, Brown, Easton, Howard and Pinder Prepared by Dr Buly Cardak 12–57 Establishing a Dividend Policy • Schools of thought: – Dividend policy does not matter (MM). – A high dividend policy is best (agency costs, preference for current income and imputation tax system). – A low dividend policy is best (issue costs, transaction costs and tax considerations). • Lease et al. (2000) conclude that shareholders’ wealth is affected by dividend policy due to market imperfections such as taxes, agency costs and asymmetric information. • Policy should be devised on a firm by firm case, depending on imperfections that have the greatest impact on the firm. Copyright 2006 McGraw-Hill Australia Pty Ltd PPTs t/a Business Finance 9e by Peirson, Brown, Easton, Howard and Pinder Prepared by Dr Buly Cardak 12–58 Dividend Policy Under Imputation • Strong incentives for tax-paying companies to pay franked dividends. – The benefits of doing so are greatest for resident. shareholders subject to marginal tax rates that are lower than the company tax rate. – On the other hand, shareholders with marginal tax rates that are higher than the company tax rate may prefer that companies retain profits (subject to the magnitude of the CGT). Copyright 2006 McGraw-Hill Australia Pty Ltd PPTs t/a Business Finance 9e by Peirson, Brown, Easton, Howard and Pinder Prepared by Dr Buly Cardak 12–59 Dividend Policy Under Imputation (cont.) • If the company tax rate and top personal tax rate were equal, then the optimal dividend policy for Australian companies owned by resident shareholders would be to pay the maximum possible franked dividends and adopt a DRP to limit the outflow of cash. Copyright 2006 McGraw-Hill Australia Pty Ltd PPTs t/a Business Finance 9e by Peirson, Brown, Easton, Howard and Pinder Prepared by Dr Buly Cardak 12–60 Dividend Policy Under Imputation (cont.) • In practice, the situation is more complex for three main reasons: – Many companies have both tax-paying resident shareholders who can use franking credits, and non-resident shareholders who cannot use them. – Equality between the company tax rate and the top personal tax rate no longer exists. – Factors other than tax: Information effects of dividends. DRPs may create free cash flows that cannot be invested profitably. Copyright 2006 McGraw-Hill Australia Pty Ltd PPTs t/a Business Finance 9e by Peirson, Brown, Easton, Howard and Pinder Prepared by Dr Buly Cardak 12–61 Agency Costs • Payment of dividends has a role in reducing agency costs — pay out of excess cash reduces opportunities for managers to destroy value by over-investing. • High-growth companies require capital, and dividend policy should account for positive NPV investment opportunities, with a low payout policy. • Conversely, mature companies with limited growth opportunities should pay out surplus cash with a higher payout policy. Copyright 2006 McGraw-Hill Australia Pty Ltd PPTs t/a Business Finance 9e by Peirson, Brown, Easton, Howard and Pinder Prepared by Dr Buly Cardak 12–62 Asymmetric Information • Dividend and share repurchase announcements have information content. • Market responds to changes in dividends, special dividends, reductions in and suspensions of dividends. • Increased ordinary dividends signal permanent increase in earnings and ability to maintain dividend level. Copyright 2006 McGraw-Hill Australia Pty Ltd PPTs t/a Business Finance 9e by Peirson, Brown, Easton, Howard and Pinder Prepared by Dr Buly Cardak 12–63 Asymmetric Information (cont.) • Special dividend or buyback indicates release of temporary free cash flow. • Managers are cautious and will not excessively raise ordinary dividends for fear of having to reduce dividend in future, a strong negative signal. • Instead, a special dividend may accompany an ordinary dividend to indicate a temporary increase in dividend. Copyright 2006 McGraw-Hill Australia Pty Ltd PPTs t/a Business Finance 9e by Peirson, Brown, Easton, Howard and Pinder Prepared by Dr Buly Cardak 12–64 Dividend Policy and Firm Life Cycle • A company’s dividend payout policy may need to change as it moves through it’s life cycle. • A new business with good growth prospects is likely to require capital and unlikely to payout dividends. • As the firm matures and has limited growth prospects and scarce positive NPV projects, excess free cash flow should be paid out as dividends to minimise agency costs. Copyright 2006 McGraw-Hill Australia Pty Ltd PPTs t/a Business Finance 9e by Peirson, Brown, Easton, Howard and Pinder Prepared by Dr Buly Cardak 12–65 Summary • Dividend policy is about the trade-off between retaining profit and paying out dividends. • Does not affect shareholders’ wealth in a perfect capital market. • Dividend policy becomes important when we • consider taxes and agency costs. • Imputation system does eliminate double taxing of dividend income and encourages higher dividend payout ratios. Copyright 2006 McGraw-Hill Australia Pty Ltd PPTs t/a Business Finance 9e by Peirson, Brown, Easton, Howard and Pinder Prepared by Dr Buly Cardak 12–66 Summary (cont.) • Dividend policy environment has been changed by recent alteration to capital gains tax laws, favouring capital gains over dividends. • Share buybacks have become an increasingly popular way to distribute cash to shareholders. • Profits earned overseas can be distributed more tax-effectively to shareholders through share buybacks. Copyright 2006 McGraw-Hill Australia Pty Ltd PPTs t/a Business Finance 9e by Peirson, Brown, Easton, Howard and Pinder Prepared by Dr Buly Cardak 12–67 Summary (cont.) • Dividends and share repurchases have a role in reducing agency costs. • Share repurchase and dividend announcements have significant effects on share prices • Combined impact of agency costs, information effects and other imperfections leads to a payout policy that needs to change as the firm moves through its life cycle. Copyright 2006 McGraw-Hill Australia Pty Ltd PPTs t/a Business Finance 9e by Peirson, Brown, Easton, Howard and Pinder Prepared by Dr Buly Cardak 12–68