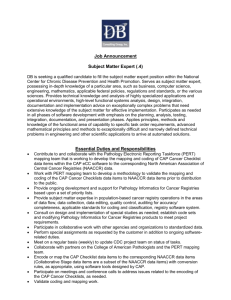

Innovations in the Use of Information for SME Lending

advertisement

Credit Reporting Systems Around the Globe Policy Seminar Inter-American Development Bank Washington, D.C. May 9, 2001 Margaret Miller, Senior Economist Corporate Strategy Group World Bank Organization of today’s presentation I. The state of the art in credit reporting results of 1999-2000 World Bank survey II. The importance of credit registries in financial markets - empirical evidence III. Public policies to support credit reporting - emerging elements of “good practice” IV. Conclusions Elements of a Credit Reporting System • the public credit registry, if one exists • private credit registries, including chambers of commerce, and banking associations • the legal framework for credit reporting • the legal framework for privacy, as it relates to this activity • the regulatory framework for credit reporting • the characteristics of other pertinent borrower data available in the economy • the use of credit data in the economy, by financial intermediaries and others • the cultural context for credit reporting I. Results of 1999-2000 World Bank survey of public and private credit registries Survey sample by country Region Public CIR Private CIR Number of obs by: Country Country Firms Latin America Africa 26 13 17 1 29 1 12 4 6 5 66 7 6 4 1 36 7 8 5 2 52 (includes 8 nations in BCEAO) W. Europe E. Europe Asia Pacific Other TOTAL The credit reporting industry is in transition, with many new entrants • The median age of private registries in the survey sample is 10 years. Thirty percent of the private registries were established since 1995. • Of the 29 private registries from Latin America, 13 were established since 1993. • Latin America led all other regions in the 1990s in the establishment of public credit registries. Public vs. Private Credit Registries Feature Public Private Source of information Participation mandatory? Positive Info? Supervised institutions Yes Varied sources Yes In some cases No Borrowers assigned Yes No a rating? Minimum loan size In some countries No Fee for service No charge or minimal charge Yes Institutional Arrangements for Private Credit Registries Institutional Type Pros Cons Private firm w/no bank ownership Private firm w/ bank ownership All types of data, independence All types of data, Special access to bank data Access to bank data Integrity Retail & non-bank data, broad cover, historical record In-depth data on commercial sector No automatic access to data Independence may be questioned Bank association Chamber of Commerce Commercial & Credit insurance firms Only bank data, only bank access No bank data, Limited funds for modernization Limited coverage, High cost per entry Who submits information to public and private registries? Public (of 29, w orldw ide) 35 30 No. of registries 25 Private (of 28 in LAC) 20 15 10 5 0 i pr om c v nk a b p ub m co nk a b p ub vt e d nk a b o oo c / n p sin a /le g ue s is rs l g ' d ns a o rd rp a ov o c r c d p d e e il & s e r c a r c t m c an re fir if n i un s nt a h rc e m Firm data collected by public and private registries Public Credit Registries (30 worldwide) Private Credit Bureaus (26 in Latin America) 30 25 20 15 10 5 0 l ) n n e n fo ee t ent ID oan ity r al era rity ess ate r(s . io lo a a m loa n r t v i e l i t r u t r n e gl.. ax n of sh em ct l a t lla atu d d ye of s ts it t of a a t o a m re p ng ow con ce tat e s co f c in u n e x n f p s s t i f e g ta ra t la ty o eo o in e o o r e n n a i i m s b rt m up pe alu am o u o y a c b t v n ro in ep g r f s o s e e n si am u N B Lo ca lg er ov e O th rn m en es ie s nc ci t ct or m en ge n ge la fo rc e lle s es rie ne ss co si ta de ra en x bu ist a n. .. da t id i ov in g tr eg pr Ta er ed i w fe La O th cr O T id Private at e N pr ov Public Pr iv s s nk nk ba ba at e at e Pr iv Pr iv Percent Distribution of data by public and private registries 100 80 60 40 20 0 Consumer Attention: Survey Responses Comparing Private and Public Registries 35 30 25 20 15 10 5 0 Private Public Access to own data Consumer Relations Department Complaints taken by phone Protocol for taking complaints Comment on record II. The importance of credit registries in financial markets empirical evidence Percentage of Banks which consult a credit registry for consumer loans no 16% yes 84% Percentage of Banks which consult a credit registry for small business loans no 7% yes 93% Importance of Registry information relative to other sources of creditworthiness 35 number of firms 30 25 20 15 10 5 0 Collateral Financial Standing of Borrower's History the Borrower with the bank Information from a credit registry is more important Information from a credit registry is less important II. Importance of credit registries in financial markets Can Credit Registries Reduce Credit Constraints? Empirical Evidence on the Role of Credit Registries in Firm Investment Decisions Arturo Galindo Margaret Miller February 2001 Empirical Evidence of the Importance of Credit Registries for Credit Markets • Jappelli & Pagano (1999) – relationship between registries characteristics (age, type of data) and credit / GNP • Barron & Staten (2000) – greater availability of information reduces default rates, improves access to credit • Kallberg & Udell (2000) – data from D&B has greater predictive power than firm financial statements • Galindo & Miller (2001) 0 ECDR MEX COL PERU ARG CHL BRZ LAC OTHER DEV U.S. CREDIT REGISTRY INDEX 100 80 60 40 20 Median Firm (Debt/Capital) v. Bureau Index (Galindo & Miller) coef = .28506701, se = .10285224, t = 2.77 UNITED S .202021 IRELAND AUSTRALI Median (Debt/Capital) BELGIUM JAPAN MEXICO CHILE SWEDEN ARGENTIN BRAZIL AUSTRIA ITALY GERMANY PORTUGAL COLOMBIA VENEZUEL PERU THAILAND SPAIN MALAYSIA RUSSIA TURKEY -.244506 -.41669 .373786 e( igen4 | X ) Bureau Index Source: World Bank survey, World Scope and authors’ calculations Empirical Model I it I it 1 c 1 2 MPK it 3 FIN it K it K it 1 Credit 4 FIN it * INDEX c 5 FIN it * i ,t GDP tc Regression Results for Credit Registry Variables CF/K*Index: -0.046 (95%) CF/K*(Pos/Neg): -0.022 (90%) CF/K*Quantity: -0.102 (95%) CF/K*Access: -0.044 (90%) Type of loans, type of report not significant Estimated sensitivity of firm investment to cash flows, with and without registries (Galindo & Miller) Sensitivity of Sensitivity of Investment to Investment to Cash Flows Cash Flows given Assuming current bureau Bureau Index=0 index ARGENTINA BOLIVIA BRAZIL CHILE COLOMBIA COSTA RICA DOMINICAN REPUBLIC ECUADOR GUATEMALA MEXICO PANAMA PERU URUGUAY 0.078 0.072 0.078 0.071 0.079 0.079 0.078 0.076 0.080 0.080 0.062 0.078 0.074 0.047 0.047 0.042 0.039 0.052 0.045 0.051 0.053 0.053 0.054 0.037 0.047 0.048 Percentage Reduction in Coefficient 39.7% 35.3% 46.2% 44.2% 33.7% 43.4% 34.5% 30.9% 32.9% 32.4% 40.8% 39.3% 35.4% Regression Results Dependent Variable: Private Credit/GDP Constant Income per capita (logs) Average economic growth Effective creditors rights Year credit registry R2 Number of observations *** Significant at 1%. ** Significant at 5%. * Significant at 10%. -17.64 (-0.220) 0.59 (0.170) 6.18 * (1.750) 13.45 *** (4.120) 0.41 ** (2.040) 0.57 28 Financial Development vs Years of Credit Registry 80 Coefficient: 0.41 t-statistic: 2.04 R2: 0.57 Private Credit/GDP 60 Panama 40 Bolivia 20 El Salvador Peru Colombia 0 Ecuador Haiti Uruguay Guatemala Brazil -20 Venezuela Chile Costa Rica Mexico Dominican Republic Argentina -40 -60 -40 -20 0 20 40 Years of Credit Registry Note: Figures adjusted by effective creditors rights, average GDP growth, and income per capita (log). 60 80 III. Public policies to support credit reporting emerging elements of “good practice” III. Emerging elements of “good practice” Legal and regulatory framework • Legal framework should encourage information sharing among lenders – review bank secrecy laws which can constrict information flows • Consideration of privacy issues important – broad privacy laws may unduly limit credit reporting • Regulatory framework with enforcement – consumers have ability to bring complaints outside judicial system • Competition policy aspects of credit info. III. Emerging elements of “good practice” Data collected and maintained • Open system, not closed network – ownership by a limited group of lenders, bank association, will discourage a broader database • Collect both positive & negative information • Maintain data for a reasonable time frame - 5 years minimum – do not delete data on non-payments when debt repaid III. Emerging elements of “good practice” Data collected and maintained • Data should be inaccessible after a certain amount of time – time limits may vary by size of loan, type of inquiry • Credit reports should not include highly sensitive information such as sexual orientation, political or religious affiliation, etc. • Other identifying information, such as gender, should be evaluated more carefully III. Emerging elements of “good practice” Data distributed • Integrity and transparency are paramount – special standing of any group, including owners or government, will discourage participation • Open system preferable, reciprocity not necessary • Access to detailed information preferable – loans described individually, not aggregates – institutions providing credit identified • Restrictions to prevent “cherry-picking” • Distribution reflects privacy considerations III. Emerging elements of “good practice” Credit reporting and bank supervision • Supervisors include financial institution’s use of credit information as part of inspections • Require publicly (government) owned financial institutions to provide data to legitimate credit reporting firms, associations • Encourage all financial institutions to participate in credit reporting III. Emerging elements of “good practice” Public Credit Registry (PCR) • Clear objectives for PCR – consult with financial institutions, private credit reporting firms • Complement, not compete, with private firms • Focus on larger loan sizes • Provide customer service if data is distributed to financial system III. Emerging elements of “good practice” Public Credit Registry (PCR) • Rating policy carefully considered – syndicated loans should have uniform rating – small loans don’t require monthly rating for PCR – requiring all loans by a borrower to have the same rating can mask differences in loan types, quality – distribution of ratings to financial system can create perverse incentives III. Emerging elements of “good practice” Consumer Attention • Borrowers should have access to their own data • Consumer-friendly procedures in place to challenge erroneous information in reasonable time frame • Record who has accessed data as part of report • Clearly established privacy policy IV. Conclusions • Credit registries are an increasingly important part of modern financial systems • Empirical evidence supports importance of credit registries for access to credit, especially by consumers and small and micro enterprises • Policy conditions, including the legal and regulatory framework, are critical in the development of robust credit reporting systems