Neolithic Europe

advertisement

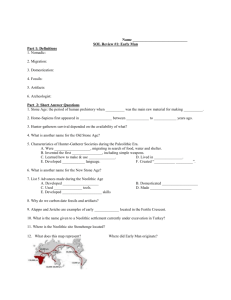

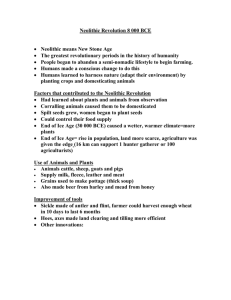

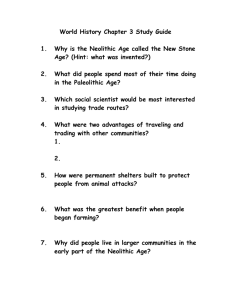

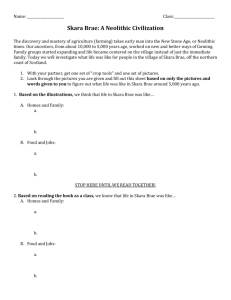

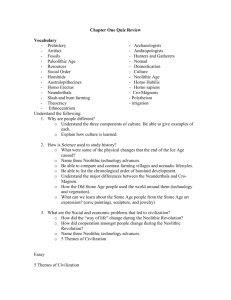

Neolithic Europe Ca. 8,000-4,000 B.P. Neolithic Neolithic Revolution: Domestication of Plants and Animals in the Old World. Defined by the presence of sedentary villages and domesticated plants and animals. The Neolithic in other parts of the Old World is defined by the appearance of these characteristics at different times – some parts of the world were still largely "preagricultural" early in this century. Neolithic expansion from 7-6,000 BP http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Image:Neolithic_Expansion.gif Neolithic economies emerge in Europe ca. 8000-6000 RCYBP Origins debated – Local development? – Diffusion from SW Asia? Neolithic economies spread rapidly – Generally earlier in southern & eastern Europe – Neolithic communities vary greatly across space & through time By 6000-5000 BP most all of Europe was utilizing Neolithic lifeways Neolithic Climate The origins and history of European Neolithic culture are closely connected with the postglacial climate and forest development. The increasing temperature after the late Dryas period during the Pre-Boreal and the Boreal (c. 8000-5500 BC, determined by radiocarbon dating) caused a remarkable change in late glacial flora and fauna. The zones Neolithic farming in Europe developed on its own lines in the four different ecological zones. These are: – the Mediterranean zone of evergreen forest and winter rains; – north of the Pyrenees, the Alps, and the Balkans, the temperate zone of deciduous forest and evenly distributed annual rainfall; – still farther north the circumpolar taiga, or coniferous forest (the only zone to remain free of agriculture and stock breeding); – and to the southeast the western end of the Eurasian Steppe. Three major divisions of the temperate zone Divisions – western Europe, from the Atlantic to the Vosges and Alps and including the British Isles; – the loesslands of central Europe, including the Ukraine and limited by the Balkans and the Harz; – and the northern province, that portion of the Eurasiatic plain lying between the Rhine and the Vistula and including Denmark and southern Sweden. The Neolithic communities that arose by 6000 BC must have developed from indigenous Mesolithic hunters and fishers. European technology and economy also had an original ideological superstructure expressed in monuments, ceramics, and personal ornaments. Cultural elements Rural economy In each of the above-mentioned provinces, the archaeological record begins with the early stages of farming, as in Thessaly. In the Mediterranean zone – early farming is connected with cardium pottery (decorated by shell impressions of Cardium edule), – cultivation of the land having been proved by pollenanalytical methods in France, as elsewhere in temperate Europe, while – northern Germany and southern Scandinavia revealed grain prints in potsherds (Ertebølle-Ellerbek). Houses Dwelling houses in Greece, Sicily, and the Iberian Peninsula were built, as in the Middle East, of pisé, or mud brick, on stone foundations. But in the Balkans and throughout the temperate zone, wood was used for the construction of gabled houses, stout posts serving to support the ridgepole and the walls of split saplings or wattle and daub. Example of Wood construction Housing Continued Around the Alps such two-roomed houses and, less often, one-roomed huts were raised on piles above the shores of lakes or on platforms laid on peat mosses. – These are the world-famous Swiss "lake-dwellings" (Uferrandsiedlungen) that have yielded such precious collections of the organic substances from wood to bread that are otherwise missing from the archaeological record. In northern Europe, too, the earliest villages consisted of two parallel, long communal houses, but these were subdivided by cross walls into 20 or more apartments, each with a separate door. Stone tools Carpenters used celts (ax or adz heads) edged by grinding and polishing of fine-grained rock or of flint where that material was available in large nodules. In Greece and the Balkans, all over central Europe and the Ukraine, and throughout the taiga, adzes were used exclusively, as in the earlier Baltic Mesolithic; in northern and Western Europe axes were preferred. In the Iberian Peninsula axes and adzes occur in equal numbers in early Neolithic graves, but the proportion of axes increased later. Often in Western Europe, and occasionally in Greece and Cyprus, celts were mounted with the aid of antler sleeves inserted between the stone head and the wooden handle--a device that was already employed in the northern European Mesolithic. Stone Tools Continued In Spain, the British Isles, and northern Europe ax heads were simply stuck into or through straight wooden shafts, but adz heads must always have been mounted on a knee shaft (a crooked stick), a method regularly used for ax heads, too, by the Bronze Age. Ax heads like those in modern use, with a hole for the shaft, were rarely used for tools, but the Danubian peasants on the loesslands may sometimes have mounted adzes in this manner. They certainly knew how to perforate stone, using a tubular borer (a reed or bone with sand as an abrasive). From them the technique was adopted by various secondary Neolithic tribes in northern Europe for the manufacture of so-called battle-axes. Ax factories and flint mines Celts, or axes, were manufactured in factories where specially suitable rock outcrops occurred, and they were traded over great distances. Products of the factories at Graig Lwyd, Penmaenmawr, North Wales, were transported to Wiltshire and Anglesey, those of Tievebulliagh on the Antrim coast to Limerick, Kent, Aberdeen, and the Hebrides. Similarly, large nodules of good flint were secured by mining in Poland, Denmark, The Netherlands, England, Belgium, France, Portugal, and Sicily. The mine shafts, which were cut through solid chalk sometimes to a depth of six meters (20 feet) with the aid only of antler picks and bone shovels, may be simple pits, but often regular galleries branching from them follow the seams of big nodules. – Although the miners appreciated the necessity of leaving pillars to support the roof, skeletons of workers killed by falls have been discovered at Cissbury, Spiennes, and elsewhere. – In the British Isles and Denmark, at least, there is evidence that the ax factories and flint mines were exploited and the products distributed by trade, for example, to the northern parts of Sweden. Still, the operators and distributors need nowhere be regarded as full-time specialists. Flint Mine in Spiennes, Belgium Pottery and Art Neolithic art, except among the hunter-fishers of the taiga, was geometric. It is best illustrated by the decoration of pottery. Pots, which were always handmade, were painted in southeastern Europe, southern Italy, and Sicily; elsewhere they were adorned with incised, impressed, or stamped patterns. Many designs are skeuomorphic--i.e., they enhance the pot's similarity to vessels of basketry, skin, or other material. But on the loesslands of central Europe and the Ukraine and in the Balkans, spirals and meanders were favourite motifs. Trade While Neolithic societies could be completely selfsufficient, growing their own food and making all essential equipment from local materials, luxury objects were transmitted quite long distances by some sort of trade. Ornaments made of the shells of the Mediterranean mussel, Spondylus gaederopus, are found all across the Balkans, up the Danube Valley, and even on the Saale and the Main. Products of factories and flint mines were, as stated, traded widely throughout a single province, such as the British Isles, and some especially valued raw materials-the yellow flint of Grand-Pressigny (France), the obsidian of Melos and the Lipari Islands--became objects of "international trade" as much as shells. But the most prized object of commerce was the amber of Jutland and Poland. Neolithic Defined Sedentary Communities Ceramics Stone Celts and Axes Domestic Foods Stone and Earthworks Structures and Sites Long-barrows were common early Neolithic elongated earthen tombs with interior timber or stone chambers containing multiple cremation burials. Passage Graves were another kind of early Neolithic collective tomb with an internal stone passage covered by a circular earthen mound. Causewayed Camps were large early Neolithic centers evidently used for gathering, feasting and ritual. – They were surrounded by a number of circles of discontinuous ditches with gaps (causeways) allowing access. – By the late Neolithic these had evidently been replaced as regional centres by henges. – These were large sites surrounded by circular earthen ditches and banks and contained circular and other arrangements of standing timber and stones. – By the late Neolithic there was also a change from multiple burials to individual burials in usually smaller earthen mounds or barrows. Important examples of tribal centers of Neolithic settlement include Skara Brae in the Orkneys, Clava in Eastern Scotland, and Oslonki, Poland . Skara Brae-Orkney Islands, Scotland Informatin from http://www.orkneyjar.com/history/skarabrae/index.html Orkney Map Skara Brae Buried into the southern shore of Sandwick's Bay o' Skaill is the Neolithic village of Skara Brae - one of Orkney's most visited sites and rightly regarded as one of the most remarkable monuments in Europe. In the winter of 1850, a great storm battered Orkney. Nothing particularly unusual about that, but on this occasion the combination of Orkney's notorious winds and extremely high tides stripped the grass from a large mound known as Skerrabra. This revealed the outline of a series of stone buildings that intrigued the local laird, William Watt of Skaill, who began an excavation of the site. By 1868, the remains of four ancient houses had been unearthed but Skerrabra was abandoned, remaining udisturbed until 1925 when another storm damaged some of the previously excavated structures. Skara Brae Housing Early Houses were circular Each house shares the same basic design - a large square room with a central fireplace, a bed on either side and a shelved dresser on the wall opposite the doorway. The later houses followed the same design as their predecessors but on a larger scale. The shape of the houses changed slightly, becoming more rectangular with rounded internal corners, and the beds were no longer built into the wall but protruded into the main living area. http://www.stonepages.com/tour/skarabraeqtvr.html Passages A winding network of passages low, narrow stone passage linked the houses of Skara Brae. This meant it was possible to travel from one house to another without having to step outside - not a bad thing in the midst of an Orkney winter! Just over one metre high, the low passages were roofed with stone slabs before being covered over with insulating midden. The height of the passages not only helped minimise drafts but could have served a symbolic, or even defensive, purpose, forcing the person entering the village to kneel or stoop. Life in Skara Brae Life in Skara Brae was probably quite comfortable by Neolithic standards. The villagers were settled farmers who, cultivating the land and raising livestock, were entirely self-sufficient. Bones found within the midden surrounding the houses shows that cattle and sheep formed the main part of the Skara Brae diet, with barley and wheat grown in the surrounding fields. To compliment their farming produce, fish and shellfish were harvested in great quantities - and perhaps kept fresh within custombuilt tanks within the houses. The island's red deer and boar were also hunted for their meat and skins. Seal meat was consumed and, on the odd occasions when they found a beached whale, its meat would have provided a welcome feast. They probably also the collected the eggs of sea-birds and possibly even the birds themselves - a task that took place in the islands until fairly recently. Religion They left no written records of their beliefs and religious practices so we are forced to make assumptions based on various objects and clues found at the sites they visited and used on a regular basis. Skara Brae's similarity to the architecture of the nearby tombs shows that ritual formed a considerable part of everyday life and in death. Given the effort put into the construction of these tombs we can also say with a degree of certainty that the dead were very important to the Neolithic Orcadians. It seems likely, therefore, that some form of ancestor worship took place but whether this took precedence over the veneration over a pantheon of deities is obviously not known. •The most enigmatic objects found in Skara Brae were four intricately carved stone balls. These items served no obvious practical purpose so are thought to have a ritual or symbolic purpose. •Although we really have no clear idea as to the purpose of the stone balls a few other examples have been found in Orkney, with around 400 found across Scotland. •The most widely accepted theory regarding these objects is that they were symbols of status, marking the owners as significant within the society. •It has even been suggested that the knobbly stones may represent the sun with rays of sunlight emanating from the central orb. Why was Skara Brae Abandoned? A common misconception is that Skara Brae was abandoned in the face of an apocalyptic disaster that caused the inhabitants to flee. This dramatic idea was proposed by Professor Gordon Childe, the archaeologist who excavated the village in 1928, and like a Northern Pompeii, it immediately caught the public's imagination. Instead, it is now thought the fall of Skara Brae was simply abandoned because Neolithic society in Orkney was changing. This change brought about different ideas and a completely different set of values and way of life. From the construction of the henge monuments at Brodgar and Stenness and the construction of Maeshowe, we can see the emergence of an elite ruling body who had the power to control the labour of a number of people. With this development, the need for all-enclosed village communities disappeared where once families depended on their tight-knit, little village communities they now were part of a larger, more widespread community, controlled by powerful tribal or spiritual leaders. Over time families dispersed across the landscape, settling once again in single individual dwellings. As more and more of these younger people drifted from the villages they were not replaced. It seems more likely that those who remained within the ancient village of Skara Brae gradually grew older and died. Burial chambers of the Neolithic Clava cairns, in North East Scotland, near Inverness. The north-east chamber The south-western cairn Plan of Clava The two cairns at Clava, with the ring cairn between them At Clava, two main tombs are laid out, open to the visitor, one at each end of the complex. Both have their entrance passage pointing in the same direction, so that on Mid-winter's day, the rays of the setting sun point right down the passage. Between the two main cairns is a monument of a rather different type known as a ring cairn. Here there is no entrance passage, and at the centre, instead of a closed chamber there is an open unroofed area where ceremonies could take place. Map of Clava The ring cairn The second stone has some 'cupmarks' near the bottom, small circular depressions, laboriously carved out for some ritual purpose. The recent radiocarbon dates show that the tombs were much later than expected: instead of being at the very beginning of the Neolithic, they come right at the very end, at around 2,000 BC. They also confirm that the whole cemetery was built at much the same time, in a single operation. The ring cairn The ring cairn at Clava under excavation. Archaeological Research at Oslonki, Poland From 1989 to 1994, six seasons of archaeological research took place at the site of Oslonki (pronounced ohs-won-key) in north-central Poland. Oslonki is located about 120 kilometers northwest of Warsaw and about 20 kilometers west of the city of Wloclawek. Archaeological research at Oslonki focuses on the study of the earliest farmers of the North European Plain, continuing work begun in 1976 at the nearby site of Brzesc Kujawski. Excavations by a team of Polish and American archaeologists have revealed a large village occupied just before 4000 B.C. with longhouses and graves. In order to understand more fully how these early farmers lived, it is important to study not only their settlement and graves but also how they used and changed the local environment. Neolithic in Poland Between 7,000 and 5,000 years ago, farming villages were established in Poland and other parts of central Europe. The understanding of the earliest European farmers is important since they represent the first instance of domesticated plants and animals being grown outside their native regions in the Near East. he first agricultural communities in Poland probably arrived from south of the Carpathians, but they quickly adapted to the new soils and landforms of the Polish uplands and plains. Excavations at Oslonki have revealed a large settlement of these early farmers with well-preserved archaeological remains. Nearly 30 trapezoidal longhouses and over 80 graves make it one of the richest such settlements in archaeological finds from all of central Europe. Of particular note is a grave excavated in 1990 with an extraordinary amount of copper, among the earliest metal in central Europe, including a copper diadem. In 1992, a grave of an archer with five bone arrow points in a quiver worn at his back was found. A ditched enclosure and palisade, also discovered in 1992, fortified the settlement (photo above right). Oslonki is among a number of fortified Neolithic settlements in north-central Europe Excavations at Oslonki