CRYPTOGRAPHY

advertisement

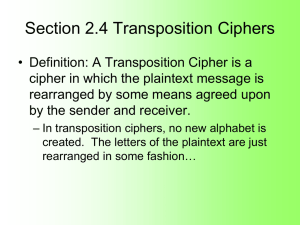

CRYPTOGRAPHY Lecture 1 3 week summer course Course structure • Format: Part lecture, part group activities • HW: – Daily assignments, some in-class and some take home. Keep these in a portfolio. – Weekly 7-10 page essays on history of cryprography (topics not in book) – Final project and presentation (you propose the topic and format) – Final grade will be determined by portfolio of work including the above. Expectations • Most work should be typed. Even work done in class should (usually) be typed and added to portfolio. • Attendance is mandatory. • Respectful behavior to your peers. • Your day is devoted to this class. General Rules • When decrypting or deciphering, all tools are fair. You may do anything legal to obtain the information you want. • However, you must disclose the methods you used. In unusual cases, you can keep some technique secret from your peers, with my approval, for a limited amount of time. Why we need secure means of communication? • Government: diplomacy is sometimes better done quietly. • Military: strategies often rely on the element of surprise. • Business: competitors will win if they know your secrets. • Love letters . . . Secret affairs . . . History of secret writing I • Herodotus chronicled the conflicts between Greece and Persia in the fifth century (499-472 BCE). • Greece was organized into small, disunited, independent city-states. Persia was a large empire (and growing) ruled by Darius, and later his son Xerxes. History of secret writing I • The Persian rulers had a long history of feuds with Athens and Sparta. Any minor problem could spark a major war. • When Xerxes built a new capital for his kingdom (Persepolis), other countries sent tributes and gifts, but Athens and Sparta did not. Xerxes was upset by this lack of respect, and began mobilizing forces to attack the Greek city-states. History of secret writing I • The Persians spent 5 years building up their forces. This was one of the largest fighting forces in history. In 480 BCE they were ready to attack. • There was a Greek exile, Demaratus, who lived in the Persian city of Susa and saw the forces being built up for war with Greece. He still felt a loyalty to his homeland, and decided to send a message to warn the Greeks of the impending attack. But how?! History of secret writing I • He scraped the wax off a pair of wooden folding tablets, wrote on the wood underneath, and covered over the tablets with wax. The apparently blank tablets got to Greece, where they realized (how?) that there may be a secret message in it, and found it. Now the Persians lost the element of surprise – and the war. Steganography • This is hidden writing or steganography. Another example is the story of Histaiaeus, who wanted to encourage Miletus to revolt against the Persian king. He shaved the head of his messenger, wrote the message on his scalp, and waited until the hair grew back. Steganography • Other examples include – The ancient Chinese would write messages on fine silk, roll it into a tiny ball, coat it with wax and swallow it . . . – Secret ink: in the 1st century, Pliny the Elder explained how the “milk” of the thithymallus plant becomes transparent after drying, but reappears upon heating. (Many organic fluids behave this way, e.g. urine) Steganography In the 16th century, the Italian scientist Giovanni Porta described how to conceal a message in a hardboiled egg by making ink from alum and vinegar and writing on the shell. The solution penetrates the shell, leaving its mark only on the egg underneath! During WWII, German agents in Latin America would photographically shrink down a page of text to a little dot, and hide it on top of a period or dotted I on a page. A tip-off allowed American agents to find this in 1941. Steganography Steganography suffers from one problem: if it is uncovered all is lost. Cryptography If we hide the message but then make it difficult to read if found, we have an added level of security. Cryptography The aim is to hide the meaning of the message rather than its presence. This can be done by scrambling the letters around. Transposition Ciphers Make an anagram according to a straightforward system (404 BCE): The sender winds a piece of cloth or leather on the scytale and writes the message along the length of the scytale. Then unwinds the strip, which now appears to carry a list of meaningless letters. The messenger would take the leather strip (sometime wearing it as a belt) and when he arrives at his destination, the receiver winds the strip back on a scytale of the same diameter. Transposition Ciphers Rail fence transposition: Round and round the mulberry bush the monkey chased the weasel r u d n r u d h m l e r b s t e o k y h s d h w a e o n a d o n t e u b r y u h h m n e c a e t e e s l Becomes: rudnrudhmlerbsteokyhsdhwaeonadonteubryuhhmneca eteesl Simple Transposition • Simple Columnar Transposition • The key information is the number k of columns. • Encipherment: Plaintext is written in lines k letters wide and then transcribed column by column left to right to produce ciphertext. This and the next few slides copied from: http://www.rhodes.edu/mathcs/faculty/barr/Math103CUSummer04/TranspositionSlides.pdf Simple Transposition: example “April come she will When streams are ripe and swelled with rain” Convert to a transposition cipher using k=10 Simple Transposition: example 1234567890 APRILCOMES HEWILLWHEN STREAMSARE RIPEANDSWE LLEDWITHRA IN AHSRL PEIIE NIOWS WRSNE IPETI LNRWR EDLLA AWCLM DTMHA SHEER EA Simple Transposition • Decipherment: If n is the length of the ciphertext,it is written column by column left to right down in a k ×(n DIV k )rectangular array with a “tail ” of length n MOD k as shown. Transcribing row by row produces plaintext. M E S S A G E The message is n=37 A N D M O R E letters long. It is set up A N D S T I L in k=7 columns. So there L M O R E U N are T I L I T E N 37 DIV 7 = 5 rows and the tail is D S 37 mod 7 = 2 HW#1a 1. Given the message NNDATEAOIIOTINHRNNODTHSGAECSUIHEMEN IECSTIWORSGAISYNOROINNETGREUNODNUIL DSCRCTP with k=8: Decipher it. HW#1a 2. Encipher a message with a given value of k. Now the groups swap messages and are given the value of k. Decipher the messages. 3. Encipher a message with a value of k between 2 and 10 and swap ciphers. Now decipher the message . . . Transposition Ciphers A double transposition offers more security: Rudnrudhmlerbsteokyhsdhwaeonadonteubryuhhmnecaeteesl Becomes u n u h l r s e k h d w e n d n e b y h m e a t e l R d r d m e b t o y s h a o a o t u r u h n c e e s Becomes unuhlrsekhdwendnebyhmeatelrdrdmebtoyshaoaoturuhncees Column Transposition A G A M E M N O N 1 4 2 5 3 6 7 9 8 key phrase convert to numbers ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ AEGMNO delete the letters not used 134579 assign them numbers 2 68 according to how they appear Example from http://hem.passagen.se/tan01/transpo.html Column Transposition A 1 s r e r G 4 e e a s A 2 n d d j M 5 d c q * E 3 a a u * M 6 r r a * N 7 m t r * O 9 o o t * N 8 u h e * key phrase convert to numbers The code is then Srer-nddj-aau-eeas-dcq-rra-mtr-uhe-oot Double Column Transposition M 5 s j s m o Y 7 r a d t t C 2 e a c r E 3 r u q u N 6 n e r h A 1 d e r e E 4 d a a o key phrase convert to numbers The code is then DEREE ACRRU QUDAA OSJSM ONERH RADTT Transposition Grille Example from http://hem.passagen.se/tan01/transpo.html Transposition Grille We need more machine gun ammunition fast xx Transposition Grille Double column Transposition How do you get back to where you started? Reverse the process. Secure transmission Steganography cryptography Transposition Substitution HW #1b • Use each of the transposition ciphers we talked about today to encode your own messages. Now swap them and (without sharing the key, or even the method of encryption) try to decipher them. Don’t feel bad if you can’t decipher. It is hard, that’s the point! • Look online for tools to help decipher transposition cipher and use them. • Read the code book’s introduction and chapter 1 pages 1-14