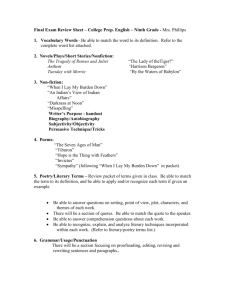

Standard E4-1

advertisement

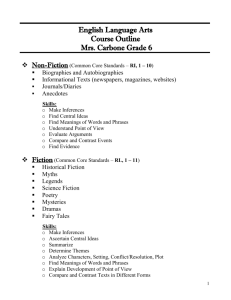

2-27-14 Based on the YA contemporary realistic fiction you’ve read, write a description of the genre. But first… QUIZ TIME! When creating assignments (especially quizzes & tests), remember: FORMAT MATTERS! From the “old” SC-ELA standards: Standard E4-1: The student will read and comprehend a variety of literary texts in print and nonprint formats. Students in English 4 read four major types of literary texts: fiction, literary nonfiction, poetry, and drama. In the category of fiction, they read the following specific types of texts: adventure stories, historical fiction, contemporary realistic fiction, myths, satires, parodies, allegories, and monologues. In the category of literary nonfiction, they read classical essays, memoirs, autobiographical and biographical sketches, and speeches. In the category of poetry, they read narrative poems, lyrical poems, humorous poems, free verse, odes, songs/ballads, and epics. From the “Introduction” section of CCSS: Through reading great classic and contemporary works of literature representative of a variety of periods, cultures, and worldviews, students can vicariously inhabit worlds and have experiences much different than their own. From the “Note on range and content of student reading”: To build a foundation for college and career readiness, students must read widely and deeply from among a broad range of high-quality, increasingly challenging literary and informational texts. Through extensive reading of stories, dramas, poems, and myths from diverse cultures and different time periods, students gain literary and cultural knowledge as well as familiarity with various text structures and elements. By reading texts in history/social studies, science, and other disciplines, students build a foundation of knowledge in these fields that will also give them the background to be better readers in all content areas. Students can only gain this foundation when the curriculum is intentionally and coherently structured to develop rich content knowledge within and across grades. Students also acquire the habits of reading independently and closely, which are essential to their future success. Book Talks: Problem Novels What do you think about having such books available in your classroom? WARNING: Contemporary realistic fiction bothers – even offends – some people. Simply having such books as options on a summer reading list (or having them in the school library) can lead to challenges. (In other words, “problem novels” can create problems for you!) What about your classroom? Have a rationale – a formal document – for any whole-class book you assign. And always have an alternate assignment for anyone who objects to reading the assigned text. Notify parents during the first week of school about all books scheduled for the whole year. Ask for any objections (so you can arrange other assignments), and have them sign a form to acknowledge their approval. Know your community and your administration. The materials below have been identified by teachers as most useful in preventing and combating censorship. (from NCTE website) Students' Right to Read Gives model procedures for responding to challenges, including "Citizen's Request for Reconsideration of a Work.“ Guidelines for Selection of Materials in English Language Arts Programs Presents criteria and procedures that ensure thoughtful teacher selection of novels and other materials. Rationales for Teaching Challenged Books Rich resource section included table of contents of NCTE's Rationales for Commonly Challenged Books CD-ROM, an alphabetical list of other rationales on file, the SLATE Starter Sheet on "How to Write a Rationale," and sample rationales for Bridge to Terabithia and The Color Purple. Guidelines for Dealing with Censorship of Nonprint Materials Offers principles and practices regarding nonprint materials. Defining and Defending Instructional Methods Gives rationales for various English language arts teaching methods and other defenses against common challenges to them. Book Clubs How “contemporary” and “realistic” is your book? Why, or under what circumstances, would you (or would you not) use it as a whole class novel? . . . as a book club selection? . . . as a book in your class library? Be prepared to talk about your selection with the rest of the class. Afterwards, we’ll talk about “problem novels” in general, and their place in the classroom. UPSIDES DOWNSIDES Looking ahead: “Author Talk” (or “author study”) due March 13. It’s like a book talk, only the subject is an author. Tell use a little about the author, maybe show us the author’s web presence, preview some books*, talk about the kinds or varieties of books the author writes, and generally try to get us interested in reading something by that author. *You’ll do TWO book talks, both books by the same author, on March 13. Author Studies: Johnson, Maureen (Hayley) McKinley, Robin (Leslie) Nix, Garth (Sara) Looking farther ahead: March 20 – bring a draft of your formal paper April 3 – formal paper due April 17 – teach minilesson from Unit Plan April 24 – Unit Plan due Start with your goals: what you want to accomplish. (Let CCSS guide your thinking process. Consider some reading standards and some writing standards.) Devise ways to measure your [students’] success. (You need to know how well you’ve accomplished those goals. What should students “know and be able to do” at the end of the unit? How will you know whether – or how well – they know or can do them? Use multiple measures.) Devise ways to teach the knowledge and skills. (Again, use a variety of approaches: different modalities, appeals to different learning styles, even options to the extent that you can offer them.) Create an “arc” for the unit. (Teach foundational knowledge and skills first. Assess as you go. It’s OK to have some HW, quizzes, and other “checks” along the way, but have one or two “big” projects/tests/papers as well.) Write a description of the whole unit, then write a detailed lesson plan for one day of the unit. You will present a portion of that lesson in class.