UnpackingStandardsFeb3

advertisement

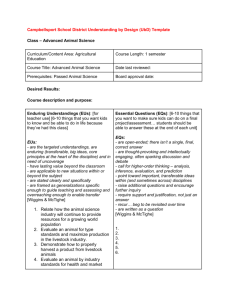

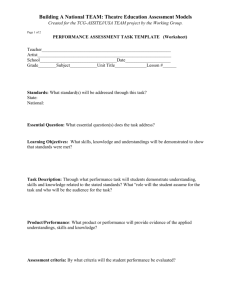

Unpacking Standards to Promote Student Understanding New Hampshire School Administrators Association February 1, 2007 Marcella Emberger ASCD Faculty Member marcyemberger@earthlink.net 1 Outcomes Participants will increase their understanding of the process of unpacking Content Standards, know the relationship among the process of unpacking and developing effective assessments & instruction, and consider how this information impacts their curriculum. 2 Advance Organizer Content Connecting Standards and Other Curriculum “Streams” The Challenges of Standards The Process of Unpacking Assessment/Instruction: Applications of Unpacking Designing a Comprehensive Curriculum Process/Content Information Bursts Reflections Increased Understanding 3 “[Curriculum streams] flow through the [educational] system, ebbing at times, then gathering strength and flowing together in a dynamic confluence.” Allan A. Glatthorn (2000) 4 Curriculum Streams Academic Rationalism Cognitive Processes Technology Personal Relevance Social Adaptation/ Reconstruction 5 Academic Rationalism, Cognitive Processes, & Technology Academic Rationalism – the heart of the curriculum is the structure of the discipline Constructivism - student as constructor of knowledge Technology - programs advocating a means-end orientation 6 Personal Relevance and Social Adaptation Student-centered curriculum - based on student/teacher interest Social Adaptation/ Reconstruction - Life Adjustment Programs (preparation for adult life) 7 8 Core Elements of a New Curriculum Emphasizes greater depth Focuses on problem solving Combines both content skills and knowledge Provides for individual differences Offers a common core to all Emphasizes the learned curriculum Attunes to personal relevance/interest 9 An Effective Curriculum has… A focus on the mission of all schooling - to enable all students to achieve worthy intellectual accomplishment as reflected in their ability to transfer their learning to worthy and authentic tasks, reflecting deep levels of understanding and key habits of mind. A curriculum and assessment framework that honors the overall mission and explicit longterm goals of academic programs to ensure that content coverage is no longer the de facto approach to lesson planning and instruction. 10 An Effective Curriculum has… A set of explicit research-based principles of learning to which all decisions about pedagogy and planning are referred. Structures, policies, job descriptions, practices, and the use of resources consistent with mission and learning principles. 11 An Effective Curriculum has… A strategy of reform centered on the constant exploration of the gap between a mission-driven vision of reform versus the current reality of schooling—i.e., a feedback-adjustment system that is ongoing, timely, and robust enough to enable teachers and students to change course as needed en route to achieve desired results. A straightforward process of planning for orchestrating the key work of schooling and school reform “backward” from the mission and desired results. 12 13 Reflection: Select one to discuss with a partner. What is your “curriculum” history? What other curriculum “streams” have impacted your philosophy? What is your vision of a new curriculum? What do your staff members understand about how our move to a new curriculum and the implementation of Content Standards impacts their teaching? 14 Content Standards Content standards are also known as learning goals or learning outcomes. Clearly written content standards provide a focus for curriculum, assessment, and instruction. Standards specify what students should know and be able to do. 15 Three Challenges of Content Standards Overload - just too many to teach! Some are too big and some are too small [Goldilocks problem] Some are too vague 16 17 Challenge #1: Overload Researchers at Mid-continent Research for Education and Learning (McRel) identified 200 standards and 3,093 benchmarks in national-and state-level documents for 14 subject areas. Classroom teachers estimated that it would take 15,465 hours to adequately address these standards. 18 Do We Have the Time? 3,093 benchmarks can not be adequately taught in the approximately 9,042 hours available (maximum) Even by extending the school year or the school day, Marzano (2001) estimated that as the current school year is structured, schooling would need to be extended from kindergarten to Grade 21 or 22. 19 Challenge #2: The Goldilocks Problem 20 Some Standards Are Too Big “The student will analyze the regional development of Asia, Africa, the Middle East, Latin America, and the Caribbean, in terms of physical, economic, and cultural characteristics and historical evolution from 1000 A.D. to the present.” What exactly does the Standard expect us to teach? What should be assessed? 21 Some Standards Are Too Small “Compare the early civilizations on the Indus River Valley in Pakistan with the Huang-He of China.” Specific and easily measurable, but what is the big idea of the discipline? Will the students end up learning “factlets” that are a matter of memorization? 22 Challenge # 3: Some Are Too Vague “Students will recognize how technical, organizational and aesthetic elements contribute to the ideas, emotions, and overall impact communicated by works of art.” The standard is so nebulous that different art teachers will interpret it in different ways, thus defeating the intention of having clear, consistent, and coherent goals. 23 New Hampshire Standards Analyzes patterns, trends, or distributions in data in a variety of contexts by determining or using measures of central tendency (mean, medium, mode), dispersion (range or variation), outliers, quartile values, or estimated line of best fit to analyze situations, or to solve problems; and evaluates the sample from which the statistics were developed (bias, random, or non-random). Organizing information to show understanding or relationships among facts, ideas, events (e.g. representing main/central ideas or details within text through charting, mapping, paraphrasing, summarizing, comparing/contrasting or outlining.) 24 Reflection Discuss with a partner: What have you observed in schools/ classrooms regarding implementing standards-based curriculum? What are your challenges related to supporting staff? 25 Unpacking Standards In light of the need for standards to be “unpacked,” how can we build consensus about what all students should understand (not just know and do) so that they can see the universal issues, patterns, and significance of what they are studying? 26 Backward Design at a Glance Stage One: Identify Desired Results & Essential Questions a. Content Standards b. Enduring Understandings c. Enabling Knowledge/Skills Stage Two: Assess Desired Results: a. Use a Photo Album, Not Snapshot, Approach b. Integrate Tests, Quizzes, Reflections and SelfEvaluations with Academic Prompts and Projects Stage Three: Design Teaching and Learning Activities to Promote Desired Results: a. W.H.E.R.E.T.O. Design Principles b. Organizing Learning So That Students Move Toward Independent Application and Deep Understanding Using Research-Based Strategies 27 Steps: Unpacking Standards: Stage 1 Identify the Big Ideas Identify Core Tasks Identify Concepts that are Important to Know and Do Determine What is Worth Being Familiar With Identify Misconceptions/ Misunderstandings 28 Unpacking Standards Using the Three-Circle Audit Process How can you “unpack” your content standards to determine their level of power or significance? Understanding by Design suggests that you use the following three-circle audit process: 29 The Understanding by Design Three-Circle Audit 1. Standards need to be interpreted and “unpacked.” 2. Staff members need to determine: a. Outer Circle: What is worth being familiar with? b. Middle Circle: What should all students know and be able to do? c. Center Circle: What are the enduring understandings students should explore and acquire? 30 Establishing Clear Priorities: Big Ideas & Transfer worth being familiar with important to know & do Big ideas & core transfer tasks “nice to know” important knowledge & skill “big ideas” & core transfer tasks at the heart of the subject 31 Establishing priorities: Math Definition of distributive property How to group & regroup “nice to know” foundational skill Equivalence, and being able to simplify, to solve real problems, using the idea big idea & core task 32 The difference a transfer task makes: How to group and regroup Process of Equivalence There is more than one way to represent numerical ideas; create a poster that can teach a younger child the concept of equivalence through everyday examples Converting fractions to percents… 33 What are Big Ideas? Big ideas are… significant and recurring concepts, principles, theories, and processes that represent essential focal points or “conceptual lenses” for prioritizing content. ways to organize discrete curriculum elements such as facts, skills, and activities. transferable ideas applicable to other settings, situations, and content areas. engaging to students in the process of “uncoverage,” discovering meaning, drawing significant inferences, and enhancing the authenticity of learning experiences. 34 Some questions for identifying truly “big ideas” Does it have many layers, not obvious to the naïve or inexperienced learner? Can it yield great power, depth and breadth of insight, into the subject? Can it be used K-12? Do you have to dig deep to really understand its subtle meanings and implications, even if anyone at any level, can have a surface grasp of it? 35 Some more questions for identifying truly “big ideas” Is it (therefore) prone to misunderstanding as well as disagreement? Are you likely to change your mind about its meaning and importance over a lifetime? Does it reflect a core idea, as judged by experts? 36 Categories for “Big Ideas” Concepts Equivalent Fractions Adaptation Themes The American Dream Ethical citizenship Issues/Debates Homeland Security Creationism vs. Evolution Problems Deforestation of the rain forests The technology gap Challenges Surviving the harsh and dangerous frontier life Processes Historiography Scientific inquiry Theories The Theory of Relativity Natural Selection Paradoxes Assumptions/ Perspectives Poverty in the Wealthiest Nation in the We are experiencing a World condition of global warming. 37 From Big Ideas to Enduring Understandings Statements or declarations of understandings comprised of two or more big ideas. 2. Framed as universal generalizations—the “moral” or essence of the curriculum story. 3. Help students to “uncover” significant aspects of the curriculum that are not obvious or may be counterintuitive or easily misunderstood. 4. Formed by completing the statement: Students will understand THAT [See Math Chart] 1. 38 Sample Enduring Understandings 1. Numbers are abstract concepts that enable us to represent concrete quantities, sequences, and rates. 2. Democratic governments struggle to balance the rights of individuals with the common good. 3. The form in which authors write shapes how they address both their audience and their purpose(s). 4. Scientists use observation and statistical analysis to uncover and analyze patterns in nature. 5. As technologies change, our views of nature and our world shift and redefine themselves. 39 Essential Questions… Are interpretive, i.e., have no single “right answer.” Provoke and sustain student inquiry, while focusing learning and final performances. Address conceptual or philosophical foundations of a discipline/ content area. Raise other important questions. Naturally and appropriately occur. Stimulate vital, ongoing rethinking of big ideas, assumptions, and prior lessons. 40 Sample Essential Questions 1. To what extent can a fictional story be “true”? 2. Why study history? What can we learn from the past? 3. Why do societies and civilizations change as technologies change? 4. How does language shape our perceptions? 5. How would our world be different if we didn’t have fractions? 41 Enabling Knowledge Objectives Once you’ve established what you want students to understand (via enduring understandings and essential questions), you’ll need to determine: What should students know in order to achieve these understandings and complete the unit successfully? What should students be able to do in order to achieve these understandings and complete the unit successfully? 42 The Structure of Knowledge Declarative (Know) Procedural (Do) Facts Skills Concepts Procedures Generalizations Processes Theories Rules Principles 43 Declarative Knowledge (Know) Facts: 1776; Annapolis is the capital of Maryland; Lyndon Johnson succeeded John F. Kennedy. Concepts: Concepts of similarity; scientific method; equivalent fractions; grammar and usage Generalizations: Tragic heroes frequently suffer because of a failure to recognize an internal character defect; Technology changes frequently produce social and cultural changes. Theories: Einstein’s Theory of Relativity; Natural Selection Rules: The Pythagorean Theorem; rules for pronouncing soundsymbol combinations in English Principles: Newton’s Laws; the Commutative Principle 44 Procedural Knowledge (Do) Skill: Focus a microscope; Decode the meaning of a word using a context cue. Procedure: Prepare and analyze a slide specimen; Summarize the main idea of a paragraph or passage. Process: Collect a variety of leaf specimens and compare their structures using a microscope; Trace the development of an author’s theme in a work of literature. 45 Reflection Use the three circle audit and the Knowledge and Skills handout. Discuss the process using one of the New Hampshire standards on Slide 24 (or another Standard with which you are familiar) 46 Using Stage 1 “Unpacking” Stage 2: Designing Diagnostic: Readiness, Interest, Learning Profile Formative: ‘Assessments for Learning’; “Everyday” Assessments; Benchmarks… Summative: Assessments of Learning Final Assessments – performance tasks; tests… 47 Pre-assessments: What’s the Point? Readiness Interest Learning Profile Growth Motivation Efficiency 48 1) To understand the student’s general readiness, interest, & learning preferences, 2) To understand the student’s readiness, interests, and learning preferences relative to the curriculum you’re about to begin teaching. 49 WHAT CAN BE ASSESSED? READINESS Skills Content Knowledge INTEREST LEARNING PROFILE • Current • Areas of Strength Interests and Weakness • Potential • Learning Interests Preferences • Talents/Passions • Self Awareness Concepts/Principles 50 Misunderstandings/Misconceptions “Long before they enter school, children also develop theories to organize what they see around them. Some of these theories are on the right track, some are only partially correct, while still other contain serious misconceptions.” Knowing What Students Know (2001) National Research Council Everything in print must be true. Science is the study of what we know about the world. When you multiply two numbers together, the answer is always bigger than both the original numbers. 51 Think “Photo Album” versus “Snapshot” Sound assessment requires multiple sources of evidence, collected over time. 52 Gather Evidence from a Range of Assessments authentic tasks and projects academic exam questions, prompts, and problems quizzes and test items informal checks for understanding student self-assessments 53 On-going Assessment: A Diagnostic Continuum Feedback and Goal Setting Pre-assessment (Finding Out) Pre-test Graphing Me Inventory KWL Checklist Observation Self-evaluation Questioning Formative Assessment Summative Assessment (Keeping Track & Checking -up) (Making sure) Conference Peer evaluation 3-minute pause Observation Whip around Questioning Exit Card Portfolio Check Quiz Journal Entry Self-evaluation Unit Test Performance Task Product/Exhibit Demonstration Portfolio Review 54 Benchmarks and Standards: Benchmarks are an interpretation of a performance standard according to age, grade, or developmental levels. Usually students construct a response or demonstrate a performance. Because there is generally no single correct answer, student products are evaluated based on judgments guided by criteria. Benchmarks require the creation of performance standards, established levels of achievement, quality of performance, or degree of proficiency. Performance standards specify how well students are expected to perform or how well they can perform processes that should be learned. 55 Value of Benchmarks Benchmarks provide… student data for classrooms, schools, and school systems. one way to monitor the progress students are making on specific indicators. information to help teachers know who has met proficiency and who hasn’t. information on what needs to be re-taught so that all students are able to reach proficiency. 56 Performance Assessments Making the Grade Your math teacher will allow you to select the method by which measure of central tendency – mean, median or mode – your quarterly grade will be calculated. Review your grades for quizzes, tests, and homework to decide which measure of central tendency will be best for your situation. Write a note to your teacher explaining why you selected that method. 57 Cornerstone Assessments Anchor the curriculum around important, recurring tasks. Require understanding and transfer of learning. Provide evidence of authentic accomplishments. (“doing the subject” and “playing the game”) 58 Sample Cornerstone Performances In science, the design and debugging of significant experiments. In history, the constructing of a valid and insightful narrative of evidence and argument. In mathematics, the quantifying and solving of perplexing or messy real-world problems. In world language, the successful translation of complex idiomatic expressions. In communication, the successful writing for specific and demanding audiences and purposes. In the arts, the composing/performing of a sophisticated piece. 59 Reflection Select one to discuss with a partner. What assessments are your staff members using to measure student progress? As a leader in your school district, what do you need to focus on in relation to assessing standards? 60 According to Wiggins and McTighe (I): “The goal of curriculum is not to take a tour of content, but to learn to use it, right from the start. Curriculum is thus inseparable from valid performance assessment task design.” 61 According to Wiggins and McTighe (II): “If autonomous transfer and meaning is the goal, then the curriculum must be designed from the start to give you practice in autonomous transfer and meaningmaking, and make clear via assessments that this is the goal.” 62 According to Wiggins and McTighe (III): “An academic curriculum must be more like the curriculum in law, design, medicine, music, athletics, and early literacy: focused from the start on masterful performance as the goal.” 63 According to Wiggins and McTighe (IV): “The most basic flaw in the writing of conventional school curriculum is that it is too often divorced from the ultimate accomplishments desired. Thus, we advise educators to design the assessment system first…We are speaking of ‘desired performances,’ authentic performances that embody the mission and program goals. Think of them as cornerstone performances reflective of the key challenges and accomplishments of the subject, the essence of ‘doing’ the subject with core content.” 64 65 What Are the Elements of an Effective Curriculum System? Ensuring horizontal, vertical, and spiraling articulation. Eliminating areas of misalignment and achievement gaps. 66 To What Extent Has Your District Ensured the Following? Horizontal Curriculum Elements: Within a grade level or grading period, required learning results are manageable, conceptually organized, learner-appropriate and complementary. Vertical Curriculum Elements: Across grade levels, learning results ensure that students build upon prior learning and prepare for subsequent learning requirements at later grade levels. Spiral Curriculum Elements: Core competencies (e.g., “metaskills”) and conceptual understandings are revisited through multiple grade levels, with learners demonstrating growing levels of proficiency and insight. 67 To What Extent Is There Alignment in Your Curriculum? The Ideal and the Organic The Taught The Written The Supported The Tested/ Assessed The Learned 68 The Levels of an Effective Curriculum Management System 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. The Ideal: The principles and values articulated in mission and vision statements. The Organic: The verbalized but unwritten values espoused by teachers and administrators. The Written: Curriculum guides, frameworks, scope and sequence documents, units, lessons. The Tested/Assessed: The components of the written curriculum that are formally evaluated via testing. The Taught: The content teachers actually present and expect students to learn. The Supported: Resources that support curriculum delivery, including schedules, materials, and training. The Learned: What students actually learn and accomplish as a result of participating in the curriculum management system. 69 …So What Can We Do About It? Come to consensus about standards. Develop a true core curriculum emphasizing depth, not breadth. Determine desired results that emphasize understanding, not just knowledge-recall. Use a range of assessment tools to create a “photo album,” not a snapshot, of student achievement. Develop instructional activities only after you have determined your desired results and assessment evidence. 70 To What Extent Has Your District Accomplished the Following? (I) 1. Articulated what all students should be able to know, do, and understand by the end of each grade level and each grading period? 2. Provided ongoing professional development to ensure that all staff members, parents, and students are in consensus about these content standards? 3. Ensured that its curriculum is “mapped” in such a way that instructors have the time to teach for deep understanding? 71 To What Extent Has Your District Accomplished the Following? (II) 4. Used this mapping process to organize the curriculum conceptually via big ideas, enduring understandings, and essential questions? 5. Designed performance standards and related benchmark assessments (both standardized and teacher-designed) to monitor students’ longitudinal progress in relationship to these desired results? 72 Going Deeper: To What Extent Do You Have the Following in Place? (III) 1. Develop and use appropriate diagnostic assessments in all courses/grade levels (pre-tests and ongoing feedback against desired results)? 2. Have subject-area committees produce valid and peerreviewed lists of “assessment tasks” around which the curriculum will be written and by which the teaching of content will be shaped? 3. Design and implement recurring tasks and rubrics related to key performance tasks related to mission and long-term program goals? 73 Going Deeper: To What Extent Do You Have the Following in Place? (IV) 4. Regularly check the gap between the intended, implemented, and attained curriculum in terms of student achievement on authentic tasks and tests? 5. Have department/grade-level teams analyze student achievement deficits in light of cornerstone assessment tasks, and collaboratively plan improvement activities? 74 Reflection: Discuss with a partner. Return to Slide 3. Use the bullets listed under Content to synthesize the major concepts related to unpacking standards and applying these concepts to curriculum design. Questions/Comments? 75 Selected References Brandt, R.S. (ed). (2000). Education in a new era. Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development. Brooks, J. and M. Brooks. (1993). The search of understanding: The case for constructivist classrooms. Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development Bruner, J.S. (1960). The process of education. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. Glatthorn, A.A. (1998). Performance assessment and standards-based curriculum. Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development Littky, D. (2004). The big picture: Education is everybody’s business. Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development Marzano, J.R. (2003). What works in schools: Translating research into action. Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development Pelligrino, J.M., N. Chudowsky, and R. Glaser. (eds.) (2001) How people learn: Brain, mind, experiences, and school. Washington D.C.: National Academy Press. Stigler, J.W and J. Hiebert. (1999). The teaching gap: Best ideas from the world’s teachers for improving education in the classroom. New York:: The Free Press. Wiggins, G, and J. McTighe. (2005). Understanding by design. Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development. 76