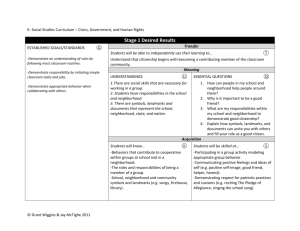

Power Point: Understanding by Design

West Side

High School

Curriculum

Mapping

.

What is curriculum mapping?

•

•

Curriculum mapping is a calendar-based (monthly) process for collecting and maintaining an ongoing database of the operational and planned curriculum throughout a learning organization.

Curriculum mapping asks teachers to design the curriculum via authentic examination, collaborative conversation, and student-centered decision making

What are the benefits?

•

•

•

•

Curriculum is available at a glance.

Enables analysis of outcomes

Facilitates faculty discussion and understanding of the curriculum.

Allows alignment of the curriculum.

Curriculum maps are designed by teachers for teachers to aid in generating ongoing collaborations focused on student learning.

Collaboration: To work together, especially in a joint intellectual effort

Eight Tenets of Curriculum Mapping

1.

2.

3.

4.

Curriculum mapping is a multifaceted, ongoing process designed to improve student learning.

All curricular decisions are data-driven and in the students' best interest.

Curriculum maps represent both the planned and day to day learning.

Teachers are leaders in curriculum design and curricular decision-making processes.

Eight Tenets of Curriculum Mapping

5.

6.

Administrators encourage and support teacher-leader environments.

Curriculum reviews are conducted on an ongoing and regular basis.

7.

Collaborative inquiry and dialogue are based on curriculum maps and other data sources.

8.

Action plans aid in designing, revising, and refining maps

Hale, J. A. (2008). A guide to curriculum mapping: Planning, implementing, and sustaining the process. Thousand

Oaks, CA: Corwin Press.

The Mapping Cycle

• Mapping is a continuous cycle of reviewing and making decisions based what has actually happened, compared and contrasted with curriculum planning through ongoing departmental and school-wide dialogue.

Mapping Is An Ongoing Process

Current curriculum and

State/Other

Standards

Organize information on to common map format

Revise map

Teach from map

Create a draft of map and share with faculty

The Empty Chair

• Whenever review teams or entire staffs meet in person, there figuratively an empty chair in the room. This chair represents all of the students in a school.

Data-driven Reviews and Collaborations

• There must be data to support changing, stopping, starting, modifying, or developing teaching practices.

• Curriculum maps are a form of data!

Why Map?

• Three common reasons why learning organizations choose to map…

Three Reasons To Map

1. Issue Motivated Initiative

School is mapping to address a specific problem or series of problems such as low test scores or graduation rates. Stakeholders are looking for quick results in a specific area or areas. However,

Curriculum Mapping is not designed to be a “quick fix” and then discarded.

Three Reasons To Map

2. School-based Initiative

School begins mapping because some administrators and/or faculty have learned about mapping and believe that it will help students improve and succeed. They know or feel there are gaps, redundancies, and absences in the curriculum and want to create horizontal and vertical integration.

Three Reasons To Map

3 . Good to Great

A school or district is looking to stay successful or to continually improve Adequate Yearly Progress

(AYP) scores. They are looking to mapping as a catalyst for ongoing curricular dialogue and professional development.

Curriculum Maps as evidence

• Curriculum Mapping is designed to provide ongoing evidence via curriculum maps and other data that empowers teachers to discover and resolve inconsistencies in curriculum that may contribute to lack of student progress.

Regardless of what is the purpose of your initiative…

• Curriculum maps are not used for teacher evaluation or punitive purposes

Curriculum Mapping

•

•

•

Systemic Second-Order Change

It is all about doing business differently.

Please realize up front that everyone will be learners for some time and as with all learners knowledge is best presented in small steps…

So, let’s take a look at the types of maps…

Four Types of Curriculum Maps

• Diary Map

• Projected Map

• Consensus Map

• Essential Map

Diary Map

A personalized map recorded by an individual person that contains data reflecting what really took place during a month of learning and instruction. Not done as a team.

Projected Map

A map that has been created by an individual person for a discipline or course before the actual yearly testing out of its “planned itinerary”

Consensus Map

A map designed by two or more educators at the school level who have come to agreement on the course learning. Serves as the planned-learning map; all who teach the course use the Consensus Map as a foundation for his or the course instruction. There is flexibility in additional topics, length of units, assessments, resources, and activities so that each teacher teaching the course can use their professional judgment.

Essential Map

A map created via a team of educators (such as a district level task force) that is representative of district learning expectations. The Essential Map serves as the base-instruction map wherein all who teach the course use the map to plan learning and create collaborative, consensus maps and/or personal projected Maps

Remember

Curriculum Mapping is NOT…

•

STATIC …Curriculum maps serve as the living, breathing, ever-changing, archived history of student learning. Mapping is formal work and takes time. The improvement in student—and teacher—learning makes both the work and time worthwhile!

Essential Understandings

Developing Understandings

• The big ideas of a subject or discipline

• A road map for the year or for several years.

• The most important part of a discipline or subject.

• Revisited throughout the year

• Revisited throughout the time the student is in school

Understandings are cumulative

•

As the student’s skill level and knowledge base grows, they will be able to explore the big idea in more complex ways. These understandings provide the purpose for students to use the knowledge and skills they are developing in the subject.

Some examples of understandings might be:

•

•

•

•

•

•

Patterns

Turning Points

Interdependence

Cycles

Communication

Revolution

•

•

•

•

•

•

Family

Choice

Equality

Conflict

Equilibrium

Interaction

Steps to Developing

Understandings:

•

•

•

Look at your Knows and Dos lists, and identify what information is most important and what are assessment priorities.

Create a title for this list of information. The title is the umbrella idea where all the information would fit. It may be necessary to group items under several smaller titles and then to ultimately combine the smaller titles to one overarching title.

Assess if this title represents an idea that is essential to working in the subject or discipline. If it does then the title is likely an Understanding Goal.

Criteria for an Understanding Goal

• Is the Understanding Goal written in language to engage students?

•

•

•

Is it likely that the Understanding Goal would make sense to students?

Is this understanding goal relevant to other subjects or is it interdisciplinary?

Can students demonstrate progress towards this

Understanding Goal through some form of “real world” project or action?

Essential Questions

Essential Questions

•

Are arguable-and important to argue about.

•

Are at the heart of the subject.

•

Recur--and should recur--in professional work, adult life, as well as in the classroom.

•

Raise more questions.

•

Raise important issues.

•

Provide a purpose for learning.

Essential Questions

•

Are provocative, enticing, and engagingly framed.

•

Are higher-order, in Bloom's sense: they are always matters of analysis, synthesis, and evaluative judgment. You must “go beyond” the information given.

•

Answers to essential questions cannot be found. They must be invented.

Essential Questions

•

•

•

•

• Essential questions often begin with . .

• Why?

• Which?

•

• How?

What if?

Why do things happen the way they do?

How could things be made better?

Which is best?

What if this happened?

Essential Questions

• Should require one of the following thought processes:

• Requires developing a plan or course of action

OR

• Requires making a decision

Essential Questions

• Must a story have a moral? A beginning, middle, and end? Heroes and villains?

• Is prejudice about race or class?

• What makes a family a community?

• Do statistics always lie?

Essential Questions

• Is gravity a fact or a theory?

• Is evolution a scientific law or a theory?

• In what way are humans animals?

• Do mathematical models conceal as much as they reveal?

(From Understanding by Design: Curriculum and Assessment , pp. 34-35)

Guiding Questions

Essential vs. Guiding Questions

Essential

•

Asked to be argued

• Designed to “uncover” new ideas, views, lines of argument

•

Set up inquiry, heading to new understandings.

Guiding

• Asked as a reminder, to prompt recall

•

Designed to “cover” knowledge

• Point to a single, straightforward fact

Guiding Questions

•

•

•

These are the smaller questions that must be answered in order to answer the big, essential question.

They provide background and guide the work.

They tend to be more topic and subjectspecific.

Guiding Questions

•

• What are the essential skills that proficient masters of content use to understand or master the content?

• For example:

•

Good readers…

•

•

•

Good writers…

Good historians…

Good mathematicians…

• Good scientists

Guiding Questions

•

•

How do good scientists investigate questions?

How do good scientists make sure their research is correct?

How do good mathematicians solve math problems that involve unknowns?

Assessments

•

•

Formative Assessments

What assessments do you use that tell you what students are struggling with and what you have to teach or re-teach?

These are your formative assessments, based on the on-going formation of knowledge. Examples might be writing conferences, lab reports, reading logs or journals, performance assessments, e.g., assessing a discussion or group work.

Assessments

•

Summative Assessments

What assessments do you use that measure students performance that tell you how much knowledge or skill your student has gained over the course of a unit or cycle? These are summative assessments (The summary of the students knowledge.)

Instructional Strategies

• What are some of the important lessons that you plan to teach, and what are the activities that you will do in class that will scaffold students skill building and provide for the accumulation of knowledge about content?

Activities

• What activities will you facilitate that will inspire students’ interest and engagement?

What methods do you use: group work, independent work, reading or writing or math workshop, accountable talk or Socratic seminar, using graphic organizers, etc.

Texts

• What texts do you have available to use or what texts do you plan to seek out? What supplementary readings will you provide?

Reflection on today’s work

• What have you completed so far on your map?

• What do you have left to do?

• What was most difficult?

• What do you wish you had more time to think about?

• What was the easiest, quickest part of the mapping?

• What would you like to see as the next steps, after the maps are complete?

Understanding By Design

Understanding by Design

Grant Wiggins and Jay McTighe

What is backward design?

Understanding by Design

Grant Wiggins and Jay McTighe

•“This book provides a conceptual framework, design process and template, and an accompanying set of design standards.”

•“It offers a way to design or redesign any curriculum to make student understanding more likely.”

Wiggins & McTighe, p. 10

Worth being familiar with.

Important to know and do.

Enduring

Understanding .

Interpretation

Explanation Application

Enduring

Understanding has six facets Self-

Knowledge

Perspective

Empathy

Wiggins & McTighe, Chapter 3

the Backward

Design

Process…

Suggests a planning sequence with three stages:

•Identify desired results

•Determine acceptable evidence

•Plan learning experiences and instruction

Curriculum Designing

versus Classroom Planning

(and Classroom Management)

Understanding by Design

Grant Wiggins and Jay McTighe

Stage One: Identify desired results

•What overarching understandings are desired?

•What are the overarching essential questions?

•What will students understand as a result of this unit or lesson?

•What essential and unit/lesson questions will focus this unit/lesson?

Understanding by Design

Grant Wiggins and Jay McTighe

Stage Two: Determine acceptable evidence

What evidence will show that students understand?

•

Performance tasks

• Projects

• Quizzes

• Tests

• Academic prompts

• Other evidence…observations, work samples, dialogues

• Student self-assessment

Understanding by Design

Grant Wiggins and Jay McTighe

Stage Three: Plan learning experiences and instruction

•What knowledge and skills are needed?

•What teaching and learning experiences will equip students to demonstrate the targeted understandings?

Now the activities can be developed!

Learning experiences and activities should evolve after identifying desired results and determining acceptable evidence.

Grant Wiggins is fond of quoting Mae West:

“If it is worth doing, it is worth doing slowly.”

Backward design takes time…