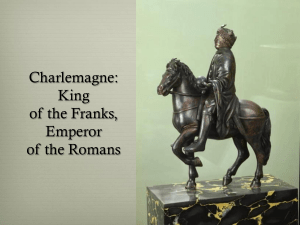

Charlemagne, Monastic, Romanesque

advertisement

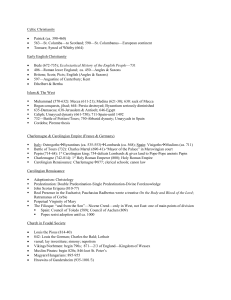

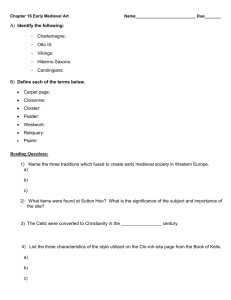

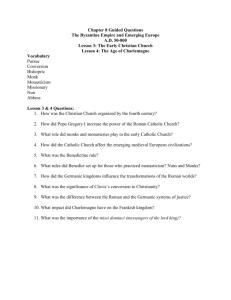

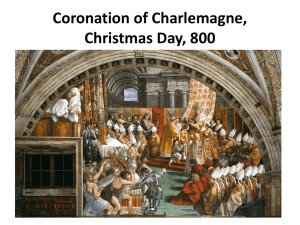

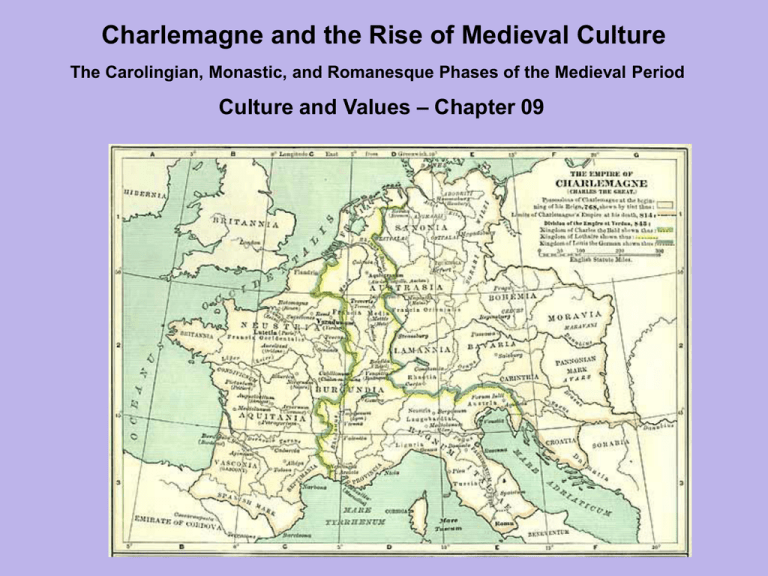

Charlemagne and the Rise of Medieval Culture The Carolingian, Monastic, and Romanesque Phases of the Medieval Period Culture and Values – Chapter 09 Outline Chapter 9: Charlemagne and The Rise Of Medieval Culture Charlemagne as Ruler and Diplomat Learning in the Time of Charlemagne Benedictine Monasticism The Rule of Saint Benedict Women and the Monastic Life Monasticism and Gregorian Chant Liturgical Music and the Rise of Drama The Liturgical Trope The Quem Quæritis Trope The Morality Play: Everyman Nonliturgical Drama The Legend of Charlemagne: Song of Roland The Visual Arts The Illuminated Book Charlemagne's Palace at Aachen The Carolingian Monastery The Romanesque Style Timeline: Chapter 9 8th-9th centuries - Irish Book of Kells 735 - Death of Venerable Bede, author of Ecclesiastical History of the English People and other religious writings 800- Charlemagne crowned Holy Roman Emperor at Rome by Pope Leo III c. 810 - Gregorian plain chant (cantus planus) obligatory in Charlemagne's churches 814 - Carolingian monasteries adopt Rule of Saint Benedict of Nursia (480-547?) 1066 - Norman invasion of England by William the Conqueror c. 1071-1112 - Pilgrimage church at Santiago de Compostela, Spain 1096-1120 - Abbey Church of La Madeleine, Vezelay c. 1125 – St. Bernard of Clairvaux denounces extravagances of Romanesque decoration 1098 - Song of Roland, chanson de geste inspired by Battle of Roncesvalles, written down after 300 years of oral tradition 1165 - Charlemagne canonized at Cathedral of Aachen Carolingian Renaissance Our attention in this chapter shifts from Byzantium to the West and, more specifically, to the rise of the kingdom of the Franks under Charlemagne. The so-called Carolingian Renaissance rekindled the life of culture after the dark period following the fall of the last Roman emperor in the West in the late fifth century and the rise of the so-called barbarian tribes. Holy Roman Empire Charlemagne's reign saw the standardization of monasticism, worship, music, and education in the church. Those reforms would give general shape to western Catholicism that, in some ways, endured into the modern period. Equally important was Charlemagne's assumption of the title of Holy Roman Emperor. That act would establish a political office that would exist in Europe until the end of World War I in the twentieth century. It also became a cause for friction between Rome and Constantinople because the Byzantine emperors saw Charlemagne's act as an intrusion on their legitimate claim to be the successors of the old Roman Empire. Seals of Charlemagne, derived from antique intaglio gems. This one depicts a Roman emperor. Feudal Society The Carolingian world was essentially rural and feudal. Society was based on a rather rigid hierarchy with the emperor at the top, the nobles and higher clergy below him, and the vast sea of peasants bound to the land at the bottom of the pyramid. There was little in the way of city life on any scale. The outpost of rural Europe was the miniature town known as the monastery or the stronghold of the nobles. The rise of the city and increased social mobility would eventually destroy the largely agricultural and feudal society as the High Middle Ages emerged in the eleventh century. The Myth of Charlemagne and the Crusades Finally there was Charlemagne as a mythic figure who eventually would be drawn larger than life in the Song of Roland. The growth of such myths always occurs because they have some deep desires behind them. In the case of Charlemagne, the desire was to describe the ideal warrior who could perform two very fundamental tasks for Europe: vanquish the Islamic powers which threatened Christian Europe and provide a model for a unified empire (the Holy Roman Empire) that would be both a perfect feudal society and one strong enough to accomplish the first task of destroying Islam. Not without reason was the Song of Roland a central poem for the firstcrusaders who turned their faces to the East. Map of Crusades, 1000 – 1200 The Book of Kells, 800 AD, Iona, off the west coast of Scotland Gospel Book of Charlemagne, Aachen, early 9th century St. Mark Ebbo St. Matthew Utrecht Psalter, The First Illustrated Psalter in the World 9th Century, Hauteviller, France, 820 - 840 Crucifixion, Palace School of Charlemagne, Ivory, 9th century Palace and Chapel of Charlemagne 792 – 805 AD, Aachen CHRISTIAN ART OF ROMANESQUE PERIOD • Romanesque means “Roman like” • Interest in monumental architecture • Massive stone arches and masonry walls support more weight than previously to yield larger, interior space • Result: • More massive pressure on side walls • Lack of windows so more wall space exists to hold up structure • Light sacrificed so images transferred to outside in stone relief. • Typically uses round arches Romanesque Churches - Interiors Church of Saint Sernin, Toulouse France: Saint-Gilles-du-Gard Benedictine Abbey of Saint-Gilles, 1140 AD Benedictine Abbey Church of Sainte-Marie-Madeleine Tympanum and south portal of St.- Pierre, Moissac. c. 1115-1135