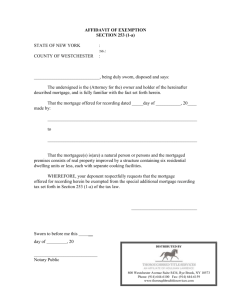

February 28

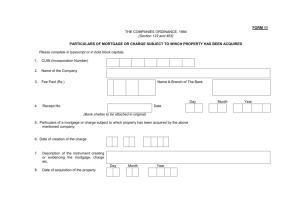

advertisement