BME 210, Wk. 6 Powerpoint - Northern Arizona University

advertisement

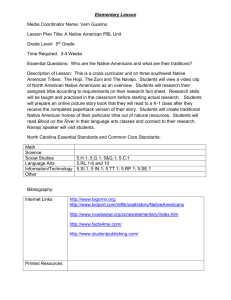

Culture-, Community-, Place-Based Education (The Case for Culturally Relevant Teaching) BME 210, Wk. 6 Powerpoint 1 My son Tsosie's chemistry teacher, Mansel Nelson, at Tuba City in the Navajo Nation began to rethink the way he taught soon after arriving in Tuba City after his best chemistry student, a Navajo girl, asked him “Why are we learning chemistry?” He began thinking of ways to make chemistry relevant to the lives of his Navajo students. He started taking local community issues and challenges and teaching chemistry around them—issues of water quality, diabetes, 2 and uranium mining. When students can’t connect what they are learning to their lives, they tend to see school as boring, which is the most common reason dropouts give for leaving school. My son’s teacher, sought to connect the “foreign” content of the mainstream textbook curriculum to actual concerns of his students and their community. His students talked, read, and wrote about these concerns in Navajo and English, and by studying these issues they developed autonomy and prepared themselves for sovereignty—taking control over their own 3 lives and the life of their community. Culture-, Place-, and Community-Based Education Students have trouble finding meaning in the onesize-fits-all decontextualized textbookand standards-based curriculum and instruction. The best way to contextualize education is to relate what students are learning to their heritage, land, and lives. 4 Besides the importance of using relevant curricular materials and learnercentered instructional practices, psychologists note the importance of choice in motivating students. Effective schools researcher Dr. Larry Lezotte declares, “we tell kids from a very young age that you are responsible for your own learning, but we don’t give them much authority over the learning.” He emphasizes that, “Choice is a powerful variable in the learning game” and that “virtually all learning is an act of choice on the part of the learner.” Lezotte quotes author Peter Block to the effect that, “If you can’t say no, yes doesn't mean anything.” 5 While students need to learn the knowledge and skills codified in state (or provincial) standards, they also need to have some choice in what they read and what type of learning projects they work on. Sovereignty is a nation making their own choices about their future, and education is the process for preparing citizens to make intelligent choices. 6 Students with low test scores in high school and in danger of not graduating were usually behind in middle school, elementary school, and when they entered kindergarten. These failed learners can enter school with very limited vocabularies and just not understand what their teachers are trying to teach. These students tend to fall further and further behind unless they receive intensive tutoring and tend to stop trying after experiencing repeated failure. The longer a child is failing and frustrated the less likely they will ever be able to catch up with more successful students. 7 To help failing students, schools need tutoring centers that are proactive, providing one-on-one corrective instruction. Lezotte outlined two principles of effective instruction. First, all students need to be placed at their appropriate level of difficulty. If their schoolwork is too easy or too hard, students will not learn much. Second, students need to be kept at this appropriate level just long enough so they can succeed, then they need to be advanced to a higher level of difficulty. 8 Intentional non-learners in schools have for one reason or another decided school is not for them. Intentional non-learners tend to be smart. They have learned that if you don’t try, then you can’t fail. Even when the intentional non-learner does well in school they can attribute their good performance on luck to avoid taking responsibility for possible failure later. They develop a philosophy that the good and bad are beyond their control. 9 Faith Spotted Eagle (Dakota) speaks about a special type of American Indian intentional non-learner who can be eaten up by “red rage.” Red rage is the result of “impact of generations of trauma, violence and oppression” that historically colonialism loaded on Indian nations. Indian students and their parents can resist being assimilated into white society in schools and can develop “oppositional identities” that reject much of what schools have to offer, including literacy, as acting “white.” She emphasizes the need for healing in Indian societies to, while not forgetting the historical oppression, get beyond it to lead a healthy life. 10 In historically oppressed societies various forms of dysfunctional behavior can arise. Besides the abuse of drugs and alcohol, the oppression can lead to intense jealousy of those tribal members who do manage to climb out of poverty—the old bucket of crabs story where the crabs in a bucket pull back down any crab that starts to escape. In schools this can be seen as peer group pressure directed at “nerds” who do well in subjects like math and science and who are accused of acting “white” and taunted with questions like, “I suppose you think you are too good for us now.” This can lead Indian and other ethnic minority students to direct their efforts at recognition in sports, which their community celebrates, rather than working for good 11 grades. Culture-, Community-, Place-based Education Culture Community Place 12 Carl Sauer wrote Man in Nature in 1939. The notes to the 2nd edition for parents and teachers states, “Carl Sauer was no easy romantic. His enthusiasms for Native America had nothing at all to do with jade bracelets, eagles’ feathers, or any number of the forms of conventional Indian tourist art. For thousands of years before the arrival of the Europeans these first Americans had tended our lands with great respect, and Carl Sauer respected them for the wisdom and good sense they employed in the administration of this bountiful task.”13 Sauer concluded in his classic geography book Man in Nature, “Being civilized means first of all learning how to make good use of the things nature provides. It means thinking of new and better ways of living. It means learning to know more and more all the time. And so we think that as we have studied how...Indians learned the ways of living more and more skillfully, we have learned how mankind has worked its way toward becoming more and more civilized.” 14 Books that describe student’s communities, often written by students, can be valuable educational tools. They can be fairly elaborate… 15 and cover topics such as traditional stories, history, current events, and anything else the community thinks is important… 16 17 or community profiles can be quite simple 18 19 In placebased education students learn about the landforms, plants, animals, and other aspects of where they live. 20 21 22 23 24 They can learn about the plants that grow where they live and their uses. 25 An ethnobotany of a region usually includes both scientific information about its plants and their tribal uses. 26 Students can go on field trips to gather local foods and document their activities with both photos and a written narrative of their activities. 27 Here, students are involved in preparing and eating the fruit of cactus called “tuna.” Traditional foods are healthier than “fast food” and most storebought food. 28 Ethnomathem atics is an approach that relates math to the cultural background of the students. 29 With ethnomathematics the teacher needs to be careful that s/he does not drift into what has been called “rain forest” math that fails to teach basic skills and and higher levels of math. 30 As well as reading about their community, students need to write about it. Gathering and writing traditional stories can be a start for students, but it should not be the end of their work. 31 T. D. Allen's advised her students at the Santa Fe Institute for the Arts to use their five senses to paint a picture in words of the scene or event and let the readers draw their own conclusions. She then had them write about something they were familiar with, their own lives. 32 Emerson Blackhorse Mitchell was one of Allen’s students who just kept on writing. His autobiography, Miracle Hill was originally published in 1967 by the University of Oklahoma Press and has been reprinted by the University of Arizona Press. 33 Students can write about their “place” in a variety of ways. Mick Fedullo who wrote Light of the Feather about his experiences getting Indian students to write poetry across the western United States. He tells students to not use adjectives like beautiful, bad, cute, good, nice, pretty and ugly that don’t really describe anything—“show don’t tell.” 34 Famous writers like Louisa Mae Alcott who wrote Little Women and Lucy Maud Montgomery who wrote Anne of Green Gables got nowhere with their writing until they took advice to write about what they knew, about the people and places they grew up around. Well known Native writers like N. Scott Momaday, Virginia Driving Hawk Sneve, Luci Tapahonso and Laura Tohe have built much of their success on the same principle. 35 Some of the students Fedullo worked with had their poetry commercially published by New York publisher Ballantine Books in Rising Voices in 1992. 36 37 Life stories and poetry are just a few of the types of writing that students need to learn how to do. Students can write and publish school newspapers and magazines as was done with the “Foxfire” publications in the Southeastern United States. This magazine was published by Ramah Navajo students. 38 Also useful are five paragraph (or more) essays and various forms of process writing where students brainstorm ideas, write drafts, discuss drafts with fellow students (and the teacher!), edit, and finally publish in some form their writing. 39 Mike Rose in his book Lives on the Boundary writes about students he met working at the UCLA Tutorial Center who got high grades on their essays in high school and then F’s for writing the same way in college. They learned to write good summaries of things they read about, but not to critically analyze what they read, which is what their university professors demanded. 40 Rose, who was born into poverty and initially did poorly in school, emphasizes again and again how a few of his teachers made all the difference in his life with their encouragement and help. Part of the encouragement and help teachers can give is to provide students some choices about what they read and write about and letting them use their experiential and cultural background to inform that writing. Of course teachers also needs to provide guidance in how this and other types of writing can be improved. 41 Daniel McLaughlin in his book When Literacy Empowers writes about a Navajo student who did well in a reservation school and then went to a Harvard summer program where just writing from “the top of her head” was not enough. She was disappointed to learn that she would need to take a remedial writing class, and later wrote to students back at her high school, “Think what you’re writing. What are you saying? What is your thesis? Thesis, thesis, thesis: everything has to relate to your main topic.” 42 The Applied Literacy Program at her school got students to develop their writing skills in Navajo and English by writing in a variety of ways, including for the school’s low-power television station and award winning newspaper. Much of their writing was based on interviewing elders, tribal officials, and other community members. 43 The Applied Literacy Program at her school got students to develop their writing skills in Navajo and English by writing in a variety of ways, including for the school's low-power television station and award winning newspaper. Much of their writing was based on interviewing elders, tribal officials, and other community members. 44 Tribal policies can promote culturally sensitive teaching. In his preface to the policies Navajo Tribal Chairman Peterson Zah wrote, “We believe that an excellent education can produce achievement in the basic academic skills and skills required by modern technology and still educate young Navajo citizens in their language, history, government and culture.” 45 The Navajo policies required schools serving Navajo students to have courses in Navajo history and culture and supported local control, parental involvement, Indian preference in hiring, and instruction in the Navajo language. They declare: “The Navajo language is an essential element of the life, culture and identity of the Navajo people. The Navajo Nation recognizes the importance of preserving and perpetuating that language to the survival of the Nation. Instruction in the Navajo language shall be made available for all grade levels in all schools serving the Navajo Nation. Navajo language instruction shall include to the greatest extent practicable: thinking, speaking, comprehension, reading and writing skills and study of 46 the formal grammar of the language.” At Rough Rock Demonstration School, the first Native-controlled school in modern times in the United States, an effort was made to educate Navajo students about their heritage. 47 Just as past work by linguists can help people recover a no longer spoken language, past work by anthropologists, even if they have ethnocentric content can be used by teachers. If the facts were “gotten wrong,” students can work with elders to help rewrite these books. This 285 page book published in 1953 by the BIA seems to be fairly accurate 48 Its author, Dr. Ruth Underhill, was a student of anthropologist Franz Boas and served as the U.S. Indian Office’s assistant supervisor of Indian education from 1934 to 1942 and then supervisor from 1942 to1948. It was printed at Haskell Institute by Indian students and drew on both published sources and interviews with many Navajos. It did not gloss over many of the failings of the Indian schools. Profusely illustrated with photos and drawings, it was designed to introduce young Navajos and BIA employees to the history and culture of the Navajo. 49 Written in the termination era after World War II, it has some assimilationist content, but it also shows a deep appreciation for Navajo history and culture. Through it and other materials, young Navajos can develop further a respect for the struggles their ancestors faced and the strength of their culture. 50 Underhill wrote, “as late as 1928, trucks arrived at Fort Apache [where chronic runaways were sent] with the [Navajo] children shackled together to prevent their jumping out. When they were once inside the school, scarcely a week passed with some group attempting to run away…. They were brought back by a Navaho policeman and, as punishment, were dressed for weeks in girls’ clothes. In their free time, they had to carry heavy logs round and round the parade ground of the old fort as punishment.” However, she also notes how Navajo leaders over the years have recognized the importance of their children being educated to live in the modern world. 51