(Section III): Wars of Independence in Latin America

advertisement

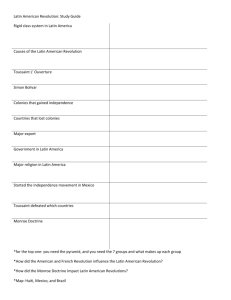

Wars and Independence in Latin America Section III (Pages 473-478) This section is about: The class structure of colonial Latin American society. How enlightenment thinkers influenced Latin American leaders. How Haiti won its independence and how other Latin American countries gained their independence by 1825. Back to the Americas: also some changes to get rights for the people. This section is a time period right after the American Revolution – which influences some of the events in Latin America. Look at the Main Ideas on page 473. The map on 476 is also a good thing to look at before we get started. Social Structure in Latin America (Mexico, Central America, South America, and the Caribbean) 1. 2. The Spanish controlled much of this area still in the late 1700’s. But, Portugal still controlled Brazil. The French, Dutch, and British had little pieces. There were two major influences on the culture of Latin America: The culture of the governing countries. The culture of the natives and slaves. Classes of Society (we saw this before) Penisulares (the highest – came from the peninsula of Spain and Portugal): had the best, most powerful jobs and made the most money. Criollos/Creoles (whites who were descendants of penisulares): owned the land and most of the mines, a little less important and jealous of the peninsulares. Mestizos (part Native American and part Spanish) and Mulattoes mix of Europeans and Africans): viewed as inferior – usually had skilled jobs and could read/write, but not allowed to own land. Native Americans and Africans: the lowest – viewed as peasants or slaves who might be able to buy their freedom. The Role of the Church The ruler of Spain was also the head of the Church in all it’s colonies. Made all decisions about money, leaders, new churches, missionaries, etc… The Latin American Church was very wealthy (in Mexico they owned about 1/3 of the land). The Church usually supported the government and society in the colonies, but didn’t say much about the treatment of Native Americans and slaves (the Church actually even owned thousands of slaves). Challenges to the System The Age of Enlightenment Reaches Latin America The Enlightenment affected Latin Americans who had contact with European ideas (of Locke, Voltaire, Rousseau, etc…). They wanted some of these changes in Latin America, too. They also heard about the Declaration of Independence, George Washington, and the American Revolution. Then, they heard about the French Revolution. They also hoped to rise up against their rulers and demand their rights (especially Criollos, Mestizos, Mulattoes, Natives, and Slaves). Independence for Haiti The first successful uprising was at Saint Domingue (Haiti). It was France’s wealthiest colony (sugar and coffee plantations with ½ million slaves). News of the French Revolution led to a Mullato and slave uprising – they wanted the same rights as French settlers. One of the main leaders: Francois Dominique Toussaint. He was a slave who learned to read and write and helped his owner family be safe during the start of the revolt. He decided to do even more and called himself L’Ouverture (the Opening). ………………….. Toussaint and his army were successful in the revolt – France passed a law freeing all slaves. Toussaint was made Lieutenant Governor and made many reforms, eventually taking total control. But Napoleon was in charge in France (and didn’t like slaves or the idea an ex-slave was running a French colony). Napoleon sent 20,000 troops to retake the island, Toussaint was captured, taken to France, and died in prison. Others took over “the cause” and eventually got rid of the French. They called their new country Haiti. This ended Napoleon’s hopes of establishing an empire in the Americas. Haiti served as an inspiration to the rest of Latin America. The Revolution Spreads When Napoleon invaded Portugal, the old King (Prince John) and his family went to Brazil. Then, Napoleon forced King Charles IV out of Spain and put his brother (Joseph B.) in charge. It was a great time for Latin American countries to start to break away from their mother countries. Simon Bolivar as Liberator One of the “liberators” of South America was Simon Bolivar. He had been a Creole aristocrat who had traveled to Europe and had heard all about the Enlightenment. He led independence movements in Venezuela and then New Grenada, until Spanish troops drove him to Haiti. He gathered supplies and troops and went back (this time defeating the Spanish). He became the new president of a union of Venezuela, Columbia, and Panama, and later Ecuador. Jose de San Martin San Martin was trying to liberate South America for years. He took his army into the Andes Mts. and then into Chile, where he was victorious. His aide, Bernard O’Higgins led the new Chilean government. San Martin kept going and liberated most of Peru. Bolivar helped him win the rest, controlling all of Peru and a place they’d call Bolivia. Brazil was different. When King John went back to Portugal, he left his son in charge. They decided to make Brazil a constitutional monarchy. Mexico and Central America (1810) A priest named Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla led a peasant revolt against the Spanish army. He wanted reform and independence, support for Native Americans, Africans, and Mestizoes, and an end to slavery. Before long, he was arrested and executed. Another priest, Jose Maria Morelos y Pavon took up the cause and issued a Declaration of Independence. He was also captured and executed. ………………… In 1821, Augustin de Iturbide (a Spanish Creole general) joined the rebels. With his help, Mexico declared it’s independence, and Iturbide continued as the new countries emperor. Mexico at the time included parts of Central America, but by 1838, they wanted their own countries. They then became Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras, Nicaragua, and Costa Rica. There were only a few small Caribbean islands left that were still British, French, or Dutch. the date is observed to commemorate the Mexican army's unlikely victory over French forces at the Battle of Puebla on May 5, 1862, Reaction in the United States All those Latin American wars cost a lot of money (for the L.A. countries). Spain and Great Britain still had some money and power and thought about going and getting them back. The United States liked that they were gone – and back in Europe. In 1823, the United States (and President Monroe) made a statement: It said, The U.S. would not interfere in Europe's business or it’s colonies that were left, but… Europe needed to stay away from the rest of the Western Hemisphere or there would be problems. This was called “The Monroe Doctrine.”