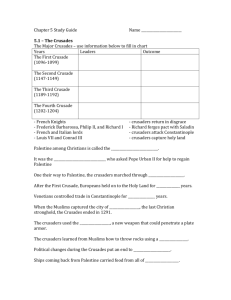

The Crusades

advertisement

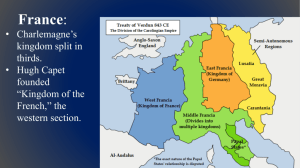

Europe to the Early 1500s: Revival, Decline, and Renaissance The high middle ages which are from the 11th through the 13th centuries were a period of political expansion and consolidation and of intellectual flowering and synthesis. The Latin or the Western church established itself as a spiritual authority independent of secular monarchies. The parliaments and popular assemblies that accompanied the rise of these monarchies laid the foundations of modern representative institutions. This period of the time witnessed a revolution in agriculture, trade and commerce. Food and product supplies increased dramatically. We also see population increases, big towns expanded, protomodern forms of banking and credit developed, and a “new rich” merchant class became ascendant in European cities. This period is also a time when the universities first started being established in Europe, particularly in Italy, Spain and France. In this period, Europe also began to escape its relative isolation from the rest of the world, which had prevailed since the early middle ages. 2 factors contributed to this increased engagement: the Crusades and renewed trade along the Silk Road linking China and Europe, made possible by the Mongol conquests in Asia. At this time, China was more advanced. In addition to the printing press, the Chinese invented the abacus, gun powder and they enjoyed a money economy unknown in the West. High middle ages period is also a time that westerners contacted with the Arab world made possible the discovery of antiquity in the writings of the ancient Greek philosophers. Those sources in turn stimulated the great expansion of western education and culture that led to Renaissance and later reformations. Years between 1300 and 1500 were years of both unprecedented calamity and bold new beginnings in Europe. France and England grappled with each other in a bitter conflict known as the “Hundred Years” war (1337-1453). Bubonic Plague, which contemporaries called it Black Death, killed as much as one third of the population in many regions between 1348 and 1350. Thereafter a schism occurred in the church (1378-1417). Then, Turks captured Constantinople and seemed to be taking dead aim at Western Europe. The late middle ages also witnessed a rebirth that would continue into the 17th century. Scholars began to criticize medieval assumptions about the nature of God, humankind and society. The “divine art” of printing was invented. The vernacular, the local language, took its place alongside Latin. In the independent nation-state of Europe, patriotism and incipient nationalism became major forces. Revival of Empire, Church and Towns From 900s till 11th century the dominance of German Empire took place in Europe and particularly over the western church. As the German empire began to crumble in the 11th century, the church long unhappy with imperial domination, declared its independence by embracing a reform movement that had erupted in a monastic order. In fact, the roots of this movement started in east-central France in 910. The aim was freeing the church from secular political influence and control. The reformers were dispatched throughout France and Italy in the late 11th century to save the clergy from wives and the church from the state. In both cases, the pope embraced their reforms. In the Middle Ages any man could theoretically become pope, since the pope was supposed to be elected by the people and the clergy of Rome. The Crusades The Crusades were organized by the Western Church at a time when there was a movement asking for reformation in the church. Crusades provided a sense of unity and support for the pope. Late in the 11th century, the Byzantine Empire was under severe pressure from the Seljuk Turks, and the Eastern emperor, Alexius I Comnenus, appealed for western help. Pope Urban II responded positively to that appeal, setting the First Crusade in motion in 1095. The Crusade had helped in many ways to the European society, particularly the pope and the nobility. Many thought that it was a very risky venture, but in reality, the western society had gained in many ways by removing large numbers of nobility temporarily from Europe, since too many idle, restless noble youths spent too great a part of their lives feuding with each other and raiding other people’s lands. The pope saw that peace and tranquility might more easily be gained at home by sending these factious aristocrats abroad, 100 000 of whom marched off in with the first crusade. It was also tempting for nobility, in turn, to possibly make fortunes in foreign wars. For the younger sons of noblemen, who in an age of growing population and shrinking landed wealth, found in crusading the opportunity to become landowners. There is also a possibility that Pope Urban II might have thought that the Crusade would reconcile and re-unite Western and Eastern Christianity. But unlike the later Crusades, which were undertaken for mercenary reasons, the early Crusades were inspired by genuine religious piety and were carefully orchestrated by a revived papacy. Pope gave them an amazing speech which indulged participants in case that they die in battle. In addition to spiritual rewards that the pope promised, the prospect of Holy War against the Muslim infidel also propelled the Crusaders. The Crusade to the Holy Land was also a romantic pilgrimage for those warriors. All these motives combined to make the first Crusade a Christian success. Along the way to the holy land, the Crusaders attempted to rid Europe of Jews and Muslims. The First Victory of Crusaders The eastern emperor welcomed western aid against advancing Islamic armies. However, the Crusaders had not assembled merely to defend Europe’s outermost borders against Muslim aggression. Their goal was to rescue the holy city of Jerusalem, which had been in the hands of the Seljuk Turks since the 7th century. To achieve this end, 3 great armies gathered in France, Germany, and Italy and taking different routes reassembled in Constantinople in 1097. The eastern capital was not happy with the motives of the Crusaders, and it was a cultural shock for the easterners; in fact they never liked the westerners anyway, but had no choice other than calling on them for help. Anyway, they accomplished what no Byzantine army had been able to do. They soundly defeated one Seljuk army after another in a steady advance toward Jerusalem, which they captured in July 1099. They created feudal states of Jerusalem, Edessa, and Antioch, which were apportioned to them as fiefs from the pope. The Crusaders remained small islands within a great sea of Muslims, who looked on the western invaders as savages to be slain or driven out. Those fierce warriors over the time became international traders and businessmen who ending up as wealthy bankers and moneylenders. The reasons for the success of the Crusader could be based on high motivation, superior military discipline and weaponry and the deep political divisions within the Islamic world that prevented a unified Muslim resistance. Then after, the Crusade armies continued their incursions on the Islamic territories. As the gathering hub for the Crusaders, Constantinople was occupied for 50 plus years. The papacy thought it will reunite the eastern and western Christianity but it did not help in anyway. The Latin presence in the east began to crumble after fortyyear-plus of reign. Islamic armies advanced again and that led to a new Crusade. Saladin (r.1138-1193) king of Egypt and Syria defeated the second Crusader and re-conquered Jerusalem, a victory so completely brilliant and unexpected that Pope Urban III was said to have dropped dead upon hearing it. With an exception of a short interlude in the 13th century, the holies of cities remained thereafter in Islamic hands until the 20th century. Towns and Townspeople In 11th and 12th centuries, most towns were small and held only about 5 percent of Western Europe’s population. They were originally dominated by feudal lords, both lay and clerical. The original purpose of creating the towns in Western Europe was to concentrate skilled laborers who could manufacture the finished goods desired by lords and bishops. Those towns, particularly port towns, led to the rise of a merchant class and increasing trade. Now that trade increased, the Western society met with a new social class alongside the nobility, clergy, and peasantry, the merchants. Merchants needed simple and uniform laws and a government sympathetic to their new forms of the countryside. The result was often a struggle with the old nobility within and outside the towns. Conflicts led towns in the high and middle ages to form their own independent communes and to ally themselves with kings against the nobility in the countryside. This development eventually rearranged the centers of power in medieval Europe and dissolve classic feudal government. New Models of Government With the emergence of a new social class, the merchants, urban autonomy gained momentum which ended up in a new model of self-government. Around 1100, the old urban nobility and the new burgher upper class merged into an urban patriciate. This was basically a marriage between those wealthy by birth and those whose fortunes came from long distance trade. As a result, an Aristocratic town council and ruling class emerged. Towns created an environment of freedom and prosperity. Over the time, towns became major force in the transition from feudal societies to national governments. During the Renaissance, towns became city states particularly in Italy. Towns also attracted Jews who plied trades in small businesses. Many became wealthy as moneylenders to kings, popes, and businesspeople. This situation encouraged suspicion and distrust among Christians and led to an unprecedented surge in anti-Jewish sentiment in the late 12th and 13th centuries. Schools and Universities In the 12th century, Byzantine and Spanish Islamic scholars made it possible for the philosophical works of Aristotle, the writings of Euclid and Ptolemy, the texts of Greek physicians and Arab mathematicians, and the corpus of Roman law to circulate among western scholars. Islamic scholars wrote thought-provoking commentaries on Greek texts that were subsequently translated into Latin and made available to western scholars and students. This resulted into intellectual ferment gave rise to western universities as we know them today. The first important one was established in 1158 in Bologna, which became the modal for the universities of Spain, Italy, and south France, and gained renown for the revival of Roman law. Then, the University of Paris became the model for northern European universities and the study of theology. In the high middle ages, the learning process was basic and people assumed that truth was already known and only needed to be properly organized, elucidated, and defended. Teachers did not encourage students to strive independently for undiscovered truth beyond the received knowledge of the experts. The education was based on accepted truths of tradition, which was in the teaching of religion. This method of study was known as scholasticism. With the arrival of Aristotle’s works in the west, logic and dialectic became the new tools for disciplining thought and knowledge. Dialectic was the art of discovering a truth by pondering the arguments against it. Society In the art and literature of the Middle Ages 4 social groups were represented: knights (those who fought as mounted and landed nobility), those who prayed (the clergy), those who labored in fields and shops (the peasantry and village artisans) and those who did the long distance trade (the merchants). After the 14th century, land and wealth counted for far more than lineage as qualification for entrance into the highest social class. Clergy was an open estate. One was a cleric by religious training and ordination, not because of birth or military prowess. Medieval Women The religious understanding and way of life shaped life of medieval women. Drawing on both the Bible and classical medical, philosophical, and legal writings pre-dating Christianity, theologians of the time depicted women as physically, mentally, and morally weaker than men. This image suggests that medieval women had two basic options in life: to became either a subjugated house-wife or a confined nun. The vast majority of medieval women were neither housewives nor nuns, but working women. The evidence suggests they were respected and loved by their husbands, perhaps because they worked shoulder by shoulder with them in running the household and often home-based businesses as well. Women appeared in virtually every “blue-collar” trade later on in the same period. They were accepted by the society to establish businesses and work in shops.