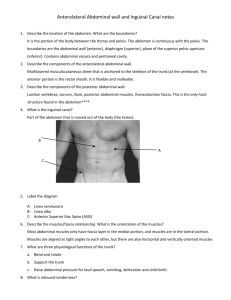

Dissection of Anterior Abdominal Wall

advertisement

Dissection of Anterior Abdominal Wall With the cadaver in the supine position, incise the skin in the midline from the xiphisternal joint to the pubic symphysis, cutting around the umbilicus. Then incise the skin 1 inch above the pubis symphysis laterally over to and a little above the iliac crest to the midaxillary line on both sides. Reflect the skin from the midline anteriorlly to the midaxillary line, leaving the superficial fascia on the anterior abdominal wall. Identify the fatty layer of the superficial fascia ( Camper's fascia)and note that it is continuous below with the fatty superficial fascia of the thigh and above with the superficial fascia of the thorax. Note that the fat is greatest in amount over the inferior half of the abdomen. Note also the terminal portion of the superficial arteries and cutaneous nerves in this layer; also observe the superficial veins. Identify the Membranous Layer of the Superficial Fascia (Scarpa's Fascia). Note That It Lies Deep to the Fatty Layer and Immediately Superficial to the aponeurosis of the External Oblique Muscle. Insert a Finger Between the Membranous Layer and the aponeurosis of the External Oblique and Separate Them Inferiorly. Note That the Finger Can Be Passed Down Medial to the Pubic Tubercle Along the Spermatic Cord and Anterior to the Body of the Pubis Into the Perineum.Lateral to the Pubic Tubercle the Finger Cannot Enter the Thigh, However,since the Membranous Layer Is Attached to the Deep Fascia of the Thigh Just Below the Inguinal Ligament. Identify the Superficial Inguinal Ring Above the Pubic Tubercle but Do Not Disturb It at This Stage. The Ring Is a Triangular Opening in the aponeurosis of the External Oblique Muscle. Make a vertical incising through the full thichness of the superficial fascia from the xiphoid process to the symphysis pubis. With the aid of a scalpel handle, carefully reflect the flaps of fascia laterally, separating the fascia from the aponeurosis of the external oblique muscle. Identify examples of anterior and lateral cutaneous nerves. Remove all the flaps of superficial fascia by making a vertical incision through the fascia in the midaxillary line. External oblique muscle. Clean the surface of the external oblique muscle and its aponeurosis. Note the attachment of the fleshy origin from each of the lower eight ribs. Here it interdigitates with the origin of the serratus anterior and the latissimus dorsi. Observe the direction of the muscle fibers. Identify the linea alba that extends from the xiphoid process down to the symphysis pubis and is formed by the fusion of the aponeurosis of the muscle of the two sides. Carefully define the margins of the superficial inguinal ring lying above the pubic tubercle. Note that it is triangular in shape and not round. In the male, identify the spermatic cord emerging from this aperture and confirm that its outer covering, the external spermatic fascia, is attached to the margins of the ring. In the female, the round ligament of the uterus emerges from the ring. Again confirm that its outer covering is attached to the margin of the ring. Identify the ilioinguinal nerve as it emerges from the lateral part of the superficial inguinal ring. Identify the inguinal ligament and note that it is formed by the lower margin of the aponeurosis of the external oblique muscle. The ligament is attached laterally to the anterior superior iliac spine and medially to the pubic tubercle. Attached to the lower margin of the ligament is the deep fascia. Internal Oblique Muscle. Free the interdigitating origins of the external oblique muscle from those of the serratus anterior as far as the midaxillary line. Incise the external oblique down the midaxillary line to the iliac crest. Now find the plane between the external oblique and the internal oblique muscles. With the fingers, free the external oblique from the internal oblique and gradually turn the upper part of the external oblique forward. Note that the fibers of the internal oblique muscle run downward and backward, that is, at right angles to the fibers of the external oblique. Continue to reflect the external oblique forward and medially toward the lateral margin of the rectus sheath to fully expose the underlying internal oblique muscle. Study the origins and insertions of the external oblique and its innervation. Make a vertical incision through the aponeurosis of the external oblique muscle 1 inch lateral to the rectus sheath and extend it down to a point 3 inches above the pubic tubercle. Turn the inferior portion of the external oblique downward and carefully examine the superior surface of the inguinal ligament. It is most important that you understand the attachments and configuration of the inguinal ligament. Note that the ligament is the inrolled lower margin of the aponeurosis of the external oblique and confirm again that it is attached to the pubic tubercle medially and the anterior superior iliac spine laterally. Carefully follow the inguinal ligament medially to the pubic tubercle, follow the fibers backward as the lacunar ligament, and note the attachment to the pectineal line. Note the continuity of the lacunar ligament with the pectineal ligament. Study the relationship of the inguinal, lacunar, and pectineal ligaments to the femoral sheath. Clean the surface of the internal oblique muscle. Define the inferior border of the muscle and note its relationship to the spermatic cord or round ligament of the uterus. Study closely the origin of the internal oblique from the inguinal ligament. Note that the internal oblique fibers arise from the lateral half of the ligament and therefore lie anterior to the deep inguinal ring. Identify the cremaster muscle passing onto the spermatic cord from the lower edge of the internal oblique muscle. Clean the ilioinguinal nerve and follow it proximally to where it emerges from the internal oblique muscle. Exposure of transversus abdominis muscle. Cut through the attachments of the internal oblique muscle to the costal margin and transect it vertically along the midaxillary line. Cut through the origin from the iliac crest and the inguinal ligament. Insert your fingers into the plane between the internal oblique and underlying transversus abdominis muscle. Reflect the internal oblique muscle forward to the lateral margin of the rectus sheath to expose fully the underlying transversus abdominis muscle and the intercostal neres. At the lateral edge of the rectus abdominis, the aponeurosis of the internal oblique is seen to split and pass anterior and posterior to the rectus abdominis; the anterior layer fuses with the aponeurosis of the external oblique muscle, and posterior layer fuses with that of the transversus abdominis. This aponeurotic covering to the rectus abdominis is called the rectus sheath. Transversus abdominis muscle. Clean the surface of the transversus abdominis and the vessels and nerves that lie on it. Note that the fibers of the transversus muscle run in a horizontal direction. Identify the lower margins of the transversus abdominis muscle and follow its fibers medially to join with those of the internal oblique to form the conjoint tendon. Examine the attachment of the conjoint tendon to pubic crest and the pectineal line. Note that the conjoint tendon lies immediately posterior to the superficial inguinal ring. Again examine the inguinal, lacunar, and pectineal ligaments and note their relationship to the conjoint tendon. Fascia transversalis. Insert the handle of the scalpel between the lower margin of the transversus abdominis muscle and the underlying fascia transversalis. Remember that this fascia lines the abdominal wall and forms the posterior wall of the inguinal canal lateral to the conjoint tendon. The fascia transversalis is tissuepaper thin, and the extraperitoneal fat can be seen through it. Deep to the fat is the peritoneal lining of the abdominal cavity. Rectus Sheath. The rectus sheath is a long sheath that encloses the rectus abdominis muscle and pyramidalis muscle (if present) and contains the anterior rami of the lower six thoracic nerves and the superior and inferior epigastric vessels and lymphatics. It is formed largely by the aponeurosis of the three anterolateral abdominal muscles. Open the entire length of the rectus sheath by a longitudinal incision just lateral to the linea alba. Identify the medial edge of the rectus abdominis muscle. Raise its medial edge and, with the finger or blunt end of the forceps, verify that it is possible to separate the rectus muscle from the posterior layer of the sheath. Note and preserve the nerves and vessels passing through the posterior wall of the sheath into the lateral part of the muscle. Reflect the lateral part of the anterior layer of the sheath by cutting free the attached tendinous intersections of the rectus muscle. Examine again the linea alba and realize that it is formed by the fusion of the aponeuroses of the three lateral muscles of the abdominal wall on the two sides. It extends from the xiphoid process down to the sympgysis pubis and separates the rectus abdominis muscles on the two sides. Understand What Is Meant by the Term linea semilunaris. This Is a Curved Ridge Formed by the Lateral Margin of the rectus abdominis Muscle. Clean the rectus abdominis and Identify the pyramidalis Muscle if Present. Transect the rectus Muscle at Its Middle and Raise the Upper and Lower Ends, Cutting the Nerves That Enter It. Identify the Superior epigastric Artery That Enters the rectus Sheath by Emerging From Beneath the Lower Margin of the Seventh Costal Cartilage and Passing Down Posterior to the rectus Muscle. Note also the inferior epigastric artery that ascends within the sheath from below. Verify the origin and insertion of the rectus abdominis and the pyramidalis muscles. Finally,remove both of these muscles. Carefylly examine the anterior and osterior walls of the rectus sheath and verify their formation from the aponeuroses of the anterior abdominal muscles. Note that the posterior wall ends below at the arcuate line, where the aponeuroses of the internal oblique and trasversus abdominis muscles pass anterior to the rectus muscle. Cut free the attachments of the internal oblique and trasversus abdominis muscles from the costal margin. Incise the latter muscle along the midaxillary line to the iliac crest. Try to preserve the underlying peritoneum intact. Reflect all the abdominal muscles and the fascia transversalis inferiorly as a unit by blunt dissection. Cut around the umbilicus to preserve its connection with the ligamentum teres of the liver. Deep inguinal ring. Before destroying the fascia transversalis in the inguinal region, pull on the spermatic cord or round ligament of the uterus from the anterior surface and identify the deep inguinal ring and the internal spermatic fascia. Confirm that the deep ring lies lateral to the inferior epigastric vessels. The Abdominal Cavity Peritoneum. The peritoneum is a serous membrane lining the walls of the abdominal cavity and clothing the abdominal viscera. The parietal peritoneum lines the walls of the abdominal cavity, and the visceral peritoneum covers the abdominal organs. The peritoneum secretes a small amount of serous fluid, which lubricates the surfaces of the peritoneum and facilitates free movement between the viscera. The potential space between the parietal and visceral layers of the peritoneum is called the peritoneal cavity. The peritoneum has the following important arrangements: 1. The peritoneal cavity is divided into the greater and the lesser sac. The greater sac is the main compartment, and it extends across the whole breadth of the abdomen and from the diaphragm to the pelvis. The lesser sac is the smaller compartment, and it lies behind the stomach, as a diverticulum from the greater sac; it opens through an oval window called the opening of the lesser sac, or the epiploic foramen. 2. A mesentery is a twolayered fold of peritoneum that attaches part of the intestines to the posterior abdominal wall, and it includs the mesentery of the small intestine, the transvers mesocolon, and the sigmoid mesocolon. 3. An omentum is a two-layered fold of peritoneum that attaches the stomach to another viscus. The greater omentum is attaches to the greater curvature of the stomach, and it hangs down like an apron in the space between the coils of small intestine and the anterior abdominal wall. It is folded back on itself and is attached to the inferiorborder of the transverse colon. The lesser omentum slings the lesser curvature of the stomach to the undersurface of the liver. The gastrosplenic omentum (ligament) connects the stomach to the spleen . 4. The peritoneal ligaments are two-layered folds of peritoneum that attach the less mobile solid viscera to the abdominal walls. The liver, for example, is attached by the falciform ligament to the anterior abdominal wall and to the undersurface of the diaphragm. The mesenteries, omenta, and peritoneal ligaments allow blood vessels, lymphatics, and nerves to reach the various viscera. Opening of Abdominal cavity and Inspection of Its Contents. When the peritoneal cavity has been opened by making a transverse incision through the parietal peritoneum lining the anterior abdominal wall at the level of the umbilicus, identify three folds of peritoneum that converge on the umbilicus from below. These cover the two lateral umbilical ligaments and the median umbilical ligament . Below the level of the anterior superior iliac spines, two additional folds may be recognized, due to the underlying inferior epigastric arteries. Examine the falciform ligament, which extends from the umbilicus to the liver. Identify the ligamentum teres in the free margin of the falciform ligament. Cut the peritoneum along the costal margin, except where the falciform ligament of the liver is attached. Reflect the remainder of the peritoneum inferiorly by cutting it down the midaxillary line on each side. Study the abdominal viscera in situ. Note the relative size, shape, and position of all the abdominal organs in the undisturbed abdominal cavity. It is important to avoid any dissection at this stage. Be prepared to find pathological changes that may have been responsible for the person's death or that may be evidence of previous disease. For example, the peritoneum may be studded by numerous secondary carcinomatous deposits that have spread from a primary lesion in one of the abdominal organs. Identify the following structures: 1. The liver, which is divided into right and left lobes by the falciform ligament. 2. The fundus of the gallbladder, which projects beneath the lower margin of the liver. 3. The stomach, which lies in the epigastrium. It is connected to the liver by the lesser omentum. 4. The greater omentum, which contains a large quantity of fat. Free up the greater omentum and reflect it superiorly to expose the transverse colon. 5. The spleen, which lies in the left hypochondrium behind the stomach and in contact with the diaphragm. 6. The coils of small intestine. Pull the greater omentum upward over the costal margin and identify the coils of jejunum in the upper left part of the abdominal cavity and the coils of ileum in the lower right part of the cavity. 7. The large intestine. The cecum is a blind pouch that lies below the level of the ileocolic junction in the right iliac region. Identify the appendix on its posteromedial surface. The cecum is continuous above with the ascending colon, then transverse colon, then descending colon and sigmoid colon.