Lingling Zhao and Paul Higgins, both at Department of Public

advertisement

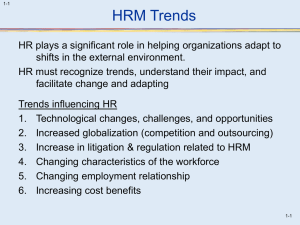

Professionalization of Human Resource Management in China Lingling Zhao and Paul Higgins, both at Department of Public Policy, City University of Hong Kong Abstract This paper identifies the process of professionalization of HRM in a Chinese context. It provides a way to explain how the professionalization of HR practitioners is occurring in China combined with an overview of Chinese professions in general, and with particular illustrative reference to the more established occupations of law and accountancy. The main purpose of the paper, however, is to identify the unique challenges and opportunities China is facing with respect to the professionalization of HRM. Through analyzing professionalization of HRM in a Chinese context, the paper provides a much needed understanding of the characteristics of the HR profession and of the strategies and policies being pursued by the state to facilitate this process. The work described in this paper was partially supported by a grant from the ESRC / RGC Joint Research Scheme sponsored by the Research Grants Council of Hong Kong and the Economic & Social Research Council of the United Kingdom (Project reference no. 9057004 RGC ref ES/J017299/1) Introduction In the past three decades, the nature of work has experienced striking changes and transformations. The dramatic alterations in new technology, government initiatives, products, human capital and labor markets have led to a reshaping of organizational structures and tasks and new labor relations. As increasing numbers of women join the labor force and efforts to improve work-life balance and flexible employment arrangements continue (Howard, 1995), novel career formats and approaches to matching individuals and work have been created. Such changes have led to dramatic innovations in social science, human resource management, public policy and governance. As these changes occur, the expertise and skills required for performing work alter as well. To keep abreast of these changes, many executives and specialized organizations have initiated professionalization programs (Curnow and McGonigle, 2006). The professional programs include the development of skill standards and professional development and certification programs in order to maintain and enhance employees' skills (Thomas, 1996; Christina, 2006). Besides, professionalization has extended over the past 200 years (Tobias, 2003), so it may be unsurprising to learn that professionalization has been studied for at least half of this time (Flexner, 1915; Curnow and McGonigle, 2006). The drive toward professionalization brings changes with regard to the evolution of human resource management (HRM) practices (McCandless Baluch, 2012): the formalization of procedures, the development of employee and employer training, transformation of the HR function, the emergence of various professional associations, a global vision of HRM and the development of specific competencies (Hartono, 2010). At the same time, the evolution of the strategic HRM discourse has led to a progressive switch from an external representation of competitive advantage to an internal examination of the skills, capacities and competencies and, more generally, of resources not easily being replaced (Bailey, 2011). All of these trends indicate the importance of the professionalization of Human Resource Management. Therefore, some questions naturally arise. For instance, where does China stand in regard to professionalization and what approaches can be used to analyze the practices and situation of HR professionalization? With China’s increased engagement in international trade and large numbers of people studying abroad as well as the fast growth of China-based multinational enterprises (MNEs), more scholarly research has been centered on the notion of HRM with Chinese characteristics (Sheldon, Sun, & Sanders, 2014). So what professionalization strategy exists in the HR authority in China and how is this different from or similar to the strategies the HR profession elsewhere and/or other professions in China? What is distinctive about the HR profession in China and what can this tell us about professionalization in general and professionalization in HR, in particular? The aim of this paper is attempt to identify the process of professionalization of HRM in Chinese context. The paper provides a way to explain how the professionalization of HR practitioners is occurring in China combined with an overview of the Chinese situation of profession in general. At the same time, the paper identifies the unique challenges and opportunities China is facing with respect to the professionalization of HRM. Definition of Professionalization That concept of professionalization has been applied in many areas including not only social science but also in other fields such as engineering, medicine, law, and accounting. In the 1950s, sociologists paid much attention to the character of professionalism (Rueschemeyer & Freidson, 1987). The main approach at this point focused on establishing the necessary features that an occupation should have in order to be recognized as a profession. If the features became too loosely specified, Wilensky (1964) suggested that modern society could entail the ‘professionalization of everyone?’ But what does professionalization mean now and what is the significance of it? In this paper, the authors adopt Millerson’s (1964) definition which views professionalization as the process by which an occupation undergoes transformation to become a profession. Alternatively, many writers have devoted time to examining the various perceptions and interpretations of professionalization. For instance, Sockett (1985) suggested that: ‘A profession is said to be an occupation with a crucial social function, requiring a high degree of skill and drawing on a systematic body of knowledge.’ Meanwhile, Wittorski (2008) refers to professionalization from three positions: one from the profession perspective – the constitution of a group of people sharing the same activities; another from a training perspective - the development of competences of a professional by its education; the third from an efficiency perspective - the fact of ‘putting in movement’ individuals within work contexts. More recently, in 2012, Hodson and Sullivan argued that professionalization can be understood as the efforts by a job-related group to raise its collaborative standing by taking on the characteristics of a profession. Such an approach was adopted by the Society of Human Resources Management (SHRM) in USA, which in 2003 conducted a survey ‘to gauge the situation of the HR profession worldwide’ (Claus & Collison, 2005). It utilized Eliot Freidson’s (2001) framework to assess six dimensions of professionalism. Moreover, Eliot formalizes professionalism by treating it as an ideal type grounded in the political economy which offers a third logic, taken to mean a more viable alternative to consumerism and bureaucracy. The dimensions are made up of a theoretical and conceptual body of knowledge and skills; identification as a profession; professional autonomy and internal control; training certification for entry and occupational mobility; service awareness and restricted external controls. Eliot (2001) encourages us to consider a world in which employees with specialized knowledge and the ability to offer society, with especially essential services, control of their work, without directives from management or the influence of free markets. Claus & Collison (2005, p.19) conclude that ‘there is still a lot of room left for the maturing of HR in terms of the various dimensions of professionalism.’ Of course, the HR profession does not operate in vacuum, HR professionalization should be considered in specific contexts. The tendencies to professionalize have been studied and the comparative means of so doing remain diverse. Nonetheless, one of the main approaches to the study of professionalization derives from an assessment of the characteristic of the profession. The Professionalization of HR Management According to research conducted by Human Resources Professionals Association (HRPA) in Canada, the professionalization of HRM is seen to be an important objective of the discipline. In 2013, one study identified that 89.4% of respondents ‘agreed’ or ‘strongly agreed’ that the professionalization of HR was of significance to them (Claude Balthazard, 2014). Although the process of professionalization of HR can be long-winded and complex, HRM has advanced quickly (Fanning, 2011). In many jurisdictions it has created a body of knowledge that can be used as education and training for skills; a certification system through which courses and examinations can be designed; a code of professional ethics to guide certified members’ behavior and, perhaps most significantly a powerful professional association (Hoyle, 1974) to promote the occupation. Drawing on a trait theory of professions, Fanning (2011) identified nine characteristics that define a profession and positioned HR in relation to them. The nine characteristics identified as defining a profession comprise the presence of a governing body; certification; education and training; a body of knowledge; code of ethics and discipline; legal status; a research base; independence; contribution to society; and recognition. Using a combination of low professional status indicators and high professional status indicators Fanning (2011) concluded that HR should be described as ‘semi-professional’ since it scored highly on some indicators but lowly on others. In other words, while some progress had been made it was not sufficient to label HR a full profession. The bigger question, however, is whether such an evolutionary step is possible or whether there are certain inherent characteristics of HR that preclude its entry into what can ultimately be demarcated as a licensed profession. This is an important consideration because the labelling of HR as a semi-professional could depict either its evolution to some full professional status later or the structural constraints of an occupational status unlikely to ever gain licensure and social closure. At the same time, “although practitioners might be keen to be recognized as a profession the accompanying responsibilities and duties of licensure that go with it might not be so welcomed” (interview with former President of the Hong Kong Institute of HRM). The definition of professionalization of Human Resources is the process by which Human Resource professionals collaboratively aspire to accomplish the recognition and status that is consistent to the established professions by matching or embracing the defining characteristics of the established professions (Claude, 2014). However, in the case of China, the concept of human resource management (HRM) is relatively new with the professionalization of HRM only at an embryonic stage at best though rapid subsequent development cannot be ruled out, especially if it gains political backing. In China, before opening up to the Western world (Sheldon et al., 2014), there was no concept of HRM and its subsequent adoption has been far from universal. In fact, most government agencies and state-owned-enterprises (SOEs) continue to use the term personnel compared to HRM, though greater adoption is reported in newly established organizations such as privately owned enterprises, joint ventures, and foreign investment firms. This represents an interesting contraposition in that while HRM has been imported into China via foreign companies it has not been adopted in sectors where such exposure is lacking. One reason for this could be that the adoption of market rather than bureaucratic organization is deemed to be dangerous in situations where national interests are at hand. There is no need, as such, for government and SOE’s to embrace market mechanisms when strategic interests are at hand. HRM, in contrast, is adopted when the independent interests of the organization are at stake and where the rules of engagement are determined on more commercial lines. This is entirely in keeping with the notion of managerialism , which is deployed when external competitive pressures are present. However, whether such marketization fosters some inherently more professional connotations or is simply presented as such to pursue the professionalization objective of the association depends on whether one values the internal or external connotations of professionalism. Professions in China Compared to other western countries, China is very different in many aspects. It has not only a unique social and cultural environment, but also a dominant Chinese government role in society(Yee, 2009). Moreover, approaches used in the process of professionalization in China share a number of similarities and differences in various industries. Currently, such classic professions as accounting, law, medicine, engineering and teaching have experienced professionalized life for more than thirty years (Brien, 2006; Warner, 2011; Yee, 2009, 2012). Yee (2009) points out that the professionalization process in China does not follow any common pattern, the success of this process (at least from the perspective of the occupation) depends on a number of conditions, in particular, the relationship of the profession with powerful actors such as the state. Any professional occupation is linked to the kind of society in which it operates—to its political and economic environments, its social structure, as well as its cultural norms (Yee, 2009). To make readers’ understanding of professionalization in China easier to understand the established cases of accounting and law will be used as initial examples. Attention will then turn to the case of HRM more specifically, whose remit, incidentally, often overlaps with the accounting (i.e. HR budgeting) and legal (i.e. industrial relations and employment law) domains. Accounting profession Unlike western accountants who took the initiative and opportunity to organize themselves into professional associations, Chinese accountants were initially not proactive in organizing themselves (Yee, 2012). Instead, the development of the Chinese accounting profession can be analyzed using the principles of market, state and community. The state has been the predominant force in the professionalization process and the forces of market and community remain under the umbrella of the state (Yee, 2009). Regarding the former, a number of important promulgations came out in 1980. In September, the Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress issued the Income Tax Law for Sino-foreign Joint Ventures. On 14 December 1980, the Ministry of Finance promulgated the Detailed Rules for Implementation of Income Tax Law for Sino-foreign Joint Ventures. This later promulgation had a significant impact on the public accounting profession in China. For the first time in the history of the accounting profession, it was stipulated that an auditor’s report required for a tax return must be signed by a Chinese Certified public accountant (CPA) (Hao, 1999, p. 292;Yee, 2012). Following on from this, the Chinese government announced in January 1985 the promulgation of the Accounting Law of the People’s Republic of China. The aim of this legislation was to ‘standardize accounting behavior, ensure that accounting documentation is authentic and complete, strengthen economic and financial management, improve economic results and safeguard the order of socialist market economy’ (Article 1). The Regulations of the People’s Republic of China on Certified Public Accountants (RCPA) was finally promulgated in July 1986. The issuance of RCPA was an important event for the public accounting profession in China. For the first time in the history of the development of the accounting profession, the status of the Chinese CPAs was legalized. The regulations also delegated the authority to CPAs to form their own professional body—the Chinese Institute of Certified Public Accountants (CICPA) (State Council of the People’s Republic of China, 1986, Article 5). Furthermore, it established consistent academic requirements for CPAs across the country (Gao, 1992, p. 15). The RCPA stipulated that only candidates with higher education degrees and at least three years practical experience after passing the uniform examination could obtain a CPA practice certificate (Wei and Eddie, 1996, p. 25). The state-accounting profession dynamic in China during the 1990s is best understood to be one of cooperation and ‘harmony’(Baker, Biondi, & Zhang, 2010). It was a period when the state – and especially Zhu Rongji – took an active interest in the development of the accounting profession, emphasizing, in particular, the requirement for a high standard of professionalism(Yee, 2012). On the economic front, the state endeavored to loosen its administrative grip over SOEs and resorted to bridge the gap in control through the use of corporatist mechanism. In this regard, the CICPA has all the hallmarks of a state professional association. It was to assist the state in managing Certified Professional Accountants (CPAs) and public accounting firms, both of which were perceived by the state (and state officials for that matter) to have an important role in monitoring the activities of SOEs(Baker et al., 2010). More importantly, the CICPA had the task of communicating policy lines of the state to its membership and, in the process, mobilizing and steering Chinese public accountants into aligning their functions with the economic agenda of the state(Yee, 2012). China’s public accounting profession serves as a foundation for a socialist market economy and concerns the future and fortune of the nation; the development of the profession is a great undertaking of lasting importance (CICPA., 1999, p. 27). The Chinese accountants responded positively to the state’s leadership, and were prepared to work with the state in facilitating its economic reforms agenda. The father and son relationship between the state and the Chinese public accounting profession means that the future development of the profession will continue under the ‘authoritative’ guiding hand of the state. Law profession The law profession in China has been under political control since its resumption in the post-Mao era when the 1980 Provisional Regulation on Lawyers defined lawyers as “workers of the state”(Brien, 2006). There has been some progress in the development of the law profession, but the profession is still characterized by a lack of independence from the state, lawyers’ inferior status in the judicial process, heavy administrative interference in legal practice and insufficient protection of lawyers’ rights (Lo &Snape, 2005). In 1996, Lawyers Law of the PRC fundamentally changed the nature of the profession from public service to private practice, redefining a lawyer as “a legal practitioner who holds a certificate to practice law and who provides legal services to society”. The Ministry of Justice retains a high degree of control; it does provide a more favorable environment for the development of the profession (Lo &Snape, 2005). The quality of lawyers has improved, their role in the legal system has been expanded, they have become better able to pursue the interests of clients, and their income from legal practice has increased greatly. Law firms operates in the form of partnerships to promote the professional identity of lawyers, and the number of lawyers has increased from close to 70,000 in 1993 to over 150,000 in 2001 (Lo &Snape, 2005). The past 25 years have witnessed phenomenal growth in the legal professions in China. At present there are more than 100,000 lawyers. Five hundred and fifty thousand entrants sat for the 2002 and 2003 unified examinations conducted by the Ministry of Justice for entry to the professions of judges, procurators, and lawyers, and about 44,000 of these passed (Lo &Snape, 2005). In 2002, the number of entrants was 300,000 but the number has reduced because the entry level for the examination has been raised(Brien, 2006). In 1980, the Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress enacted the Regulations for Lawyers (Provisional), before these regulations were replaced in 1996 by the Lawyers’ Law. Legal professionals are playing an increasingly important part in China’s society. The professionalization of the legal profession from 1996 to the present is particularly marked by a switch from the development of the All-China Lawyer’ Association to self-regulation. In fact, professionalization can be indicated by the growing independence of the national association in managing the legal profession and the increasing autonomy of lawyers in their practice (Lo &Snape, 2005). Local lawyers’ associations have gradually set up in urban cities across the country such as the Chief of the Beijing Justice Bureau, Sun Changli, served as the Chairman of the Beijing Lawyers’’ Association. In the aspect of qualifying examination, Ministry of Justice controlled the qualification of legal professionals. There were also a set of code of ethics lawyers should follow. “Lawyers’ Ten Wanted and Ten Not Allowed” was issued in 1990 while the first formal document “The Norms on Professional Ethics and the Discipline of Practice of Lawyers” appeared in 1993(Lo &Snape, 2005). Related penal regulations issued later to discipline lawyers who are found guilty of misconduct. Many researchers (Gao, 2002; Lo &Snape, 2005; Brien, 2006; Clark, 2008) suggest that developments in the state’s support for the rule of law, professional standards, and the role of the lawyers’ associations are needed if the legal system and the law profession are to play their necessary role in China’s modernization. What HRM professionalization strategies exist in China? In China, the authoritarianism associated with the Communist Party regime, together with the promotion of socialist democracy and the influence of traditional culture, have combined to shape a very different system of power distinctive from the kind of interest group dynamics experienced in the west (Yee, 2012). The competing demands made upon the state and how the state influences the outcome of the professionalization process is particularly highlighted in studies that look at inter- and intra-professional rivalries (Yee, 2012). Drawing on the themes of state power influence, normative education programs in HRM, HRM certification mechanism and the establishment of HR professional associations, this section examines the HRM professionalization strategies that currently exist in China. The state power influence In the process of building human resource management policies and practices, countries often adopt two main approaches: hard ways - directly through HRM laws and regulations - and soft ways - through government-piloted initiatives and campaigns aimed to promote certain desirable HRM practices and management behavior (Godard 2000 2; Martinez Lucio and Stuart 2004; Mellahi 2007,Cooke, 2011). Both of these forms have different effects but should not be overrated, especially in a Chinese context because of the absence of enforcement powers (Collings & Mellahi, 2009; Cooke, 2011). China is a one-party-led state which has a comparatively more stable political power than other democratic states (Cooke, 2011). The central government and its extended sectors control almost all aspects of management in all industries. However, although the central government also exerts power on local governments and its agencies the relative autonomy of these distinct sectors means that they can possess their own agenda and interests that may undermine the state’s HRM strategic initiatives (Cooke, 2011). As such, many HRM strategies and policies that exist in China contain local characteristics that reflect the ‘harmonious’ diversity of many different places. China’s rapid modernization since 1979 has involved the transmission and transfer of ideas and techniques that have enhanced the transition to a market economy. In some, particularly foreign imported cases, these have included the embedding of particular notions of HRM as the dominant prescriptive, particularly for advanced organizational policies and practices related to the management of employment. In theory and practice then, HRM is gradually replacing the term ‘personnel management’ that administered employment relations in the centralized, planned and state-owned Maoist political economy (Ding and Warner 2001), though legacies remain strong in government and state-owned sectors. Otherwise, foreign direct investment has been a major carrier of new approaches, first, via joint ventures and subsequently and, more completely, by the opening to wholly foreign-owned enterprises (Sheldon, Sun, Sanders, 2014). For the foreign-funded Multinational Corporations (MNC), in order to increase capital and managerial competence for domestic organizations, they are permitted to join the Chinese market as wholly owned foreign firms after 1998 (Bjo¨rkman and Lu 2001; Child 2001,Cooke, 2011). Such prestigiously viewed corporations as IBM and Wal-Mart were able to bring advanced management ideas and practices into the China market, which were promoted and encouraged as outstanding models by local government, deviating perhaps from a more conservative central government stance. Nonetheless, many HR professional practices, such as job analysis, performance management and quality management, were spread and shared by these groundbreaking MNCs (Cooke,2004 & 2011). Various HRM practices emerged with the development of foreign-owned recruitment, headhunting agencies and HR consultancy firms due to the opening labor market. For instance, the ‘Regulation on Talent (Employment) Market Management’ was issued in 2002 in order to increase advanced services from foreign-owned employment agency firms. The entrance of well-established foreign owned HR operators has created the HR outsourcing and consulting market, which together with MNCs in other industries, have played an important role in raising the HR standard to conform to the institutional requirements of the market. Moreover, this has occurred in a relatively short period of time, given the low starting point of the profession (Cooke, 2011). Although HRM remains largely a private-sector/foreign implanted concept, the government still exerts an influence both directly and indirectly. For example, in 2008, the government issued the ‘Thousand Talents Plan’ in order to attract talents from overseas. This has an indirect influence on HRM prevalence given its likely foreign acquaintance with such processes. Likewise, the government could also indirectly influence HRM prevalence by implementing HRM initiatives through State-owned Enterprise (SOEs). Alternatively, as a more direct measure of the government’s influence, it has issued a range of HRrelated policies and regulations that impact all organizations and established a number of qualified bodies as well as research centers/ institutes. From the legislative view, it has passed the Labor Law, the Vocational Education Law, and the Enterprise Law. These regulations provide a source of professionalization potential by giving HR practitioners a mandate to determine the actions of others (i.e. the organization must abide by the law) and, therefore, by exerting coercive power. Regarding research, the China Professional Managers Research Centre, the China Institute for Internationalizing Professional Managers and the Leadership Assessment Centre has all been established. In addition, the authorities have sanctioned the provision of imported and homegrown MBA programs which entail MNCs training collaboration. Hence, in all of these ways, and as noted for accountancy and law above, state power is able to provide large-scale intervention in the process of professionalization of HRM in China. This occurs both by setting strategic agendas at the top level and then rolling them out through various state agencies and actors at lower levels (Cooke, 2011). For example, China Human Resource and Social Security Ministry guides the whole HRM relevant policies and initiatives at national level. Other local governments have their own institutes and Human Resource Associations at the lower level to implement HRM strategies according to national policies and strategies. Normative education programs in HRM DiMaggio and Powell (1982) claim that two aspects of professionalization are important. One is formal education programs and bodies of knowledge produced by university specialists; the second is the growth and elaboration of professional networks that span organizations and across which new models diffuse rapidly. Universities and professional training institutions are important centers for the development of organizational norms among professional managers and their staff. MBA/EMBA programs fill ‘the management education gap at all levels and in all sectors’ and contribute to the development of powerful management networks nationwide (Southworth 1999, p. 330). The main reasons why participants undergo MBA/EMBA training programs are to explore new knowledge and to develop connections and network for future career advancement. ‘Guanxi (personal connections)’is very important in Chinese environment as a crucial substitute for formal institutional support. Another source has been the emergence in China of Western-style business schools and the teaching of Western-style business curricula at Chinese universities (Warner and Goodall 2009; Sheldon, Sun, Sanders, 2014). Nonetheless, these popular programs do provide various management knowledge including HRM related courses. There are more than 2000 universities in China, one-seventh of them offering HRM degree programs at different levels (Sheldon et al., 2014). Almost all the graduates who hold HRM relevant degrees are engaged in HR industry and add more professional employees in different organizations. There are more faculty members in China’s business schools who are doing research in HR or related fields, and the quality of HRM research is improving all the time (Sheldon, Sun, Sanders, 2014). Meanwhile, the central government’s HRM strategies include increasing nationwide training programs for different labor force and funding management training and education of HRM through various institutes and business schools. The first stage in the state’s attempt to professionalize SOE managers and state cadres was from the mid-1980s to the mid-1990s (Cooke, 2011).There is an increasing demand for professional managers with expertise in HRM. Therefore, training Chinese HR managers became an urgent requirement for all enterprises concerned. Thousands of SOE managers and government officials were sent to the state-funded and purpose-built institutes or schools of economics and management located in top tier universities for education. This was typically full-time for 2–3 years, leading to a diploma or bachelor degree qualification in economics and management. In addition, part-time university/ college qualification education programs were available for professionals and managerial candidates who sought career advancement, as educational qualification became a prerequisite for promotion in the state sector(Cooke, 2011). The second stage entailed the fast development of business schools and MBA/EMBA and short-term executive management training programs nationwide. The demand for up-to-date western management theories and applications surged and resulted in the rapid growth of business schools and MBA/EMBA programs. According to Southworth (1999), when the China European International Business School was established in late 1994, there were about 500 MBA graduates in China, half of them having been educated as management elites at the China Europe Management Institute in Beijing between 1984 and 1994. A more recent phenomenon is that the government is taking advantage of foreign MNCs’ corporate universities in China by sending senior managers from key SOEs for training and development (Wang and Wang 2006). Even though there has been fast growth in the provision of HRM courses and training programs in China, their effect and benefits have not been taken full advantage. This is because there is lack of post-training evaluation insufficient organizational mechanisms to provide opportunities for candidates to apply what they have learned into advancing organization effectiveness (Cooke, 2011). So the next step of HRM education is to make it more applicable and practical for various learners. HR professionals graduating from universities and institutes with HR relevant degrees will constitute the main part of the HR practitioners market. HRM certification mechanism At present, most of personnel departments in private Chinese enterprises have transferred to Human Resource departments. However, HR practitioners who master professional HRM knowledge and have professional qualifications are extremely rare. According to a research conducted by Ministry of Human Resource and Social Security in 2009, the HR talent gap has reached 50 million people in China and, as a conservative estimate; this represents around 40,000 people in Shanghai, 30,000 people in Dalian - a city in Liaoning Province. One of state-led initiatives to professionalize HRM entailed the Ministry of Labor and Social Security introduction of the HR professional qualification accreditation system in 2005 (Development and Management of Human Resources 2006). It became the largest occupational assessment event at the time, and a total of 200,000 people had taken the examination by 2006. In 2006, major changes took place to improve the examination system for the HR professional qualifications. The revised system emphasizes knowledge renewal and the development of competence. It marks a departure from the existing emphasis on degree qualifications in the profession. According to the Development and Management of Human Resources (2006a), the popularity of the HR professional qualification accreditation system will help develop the HR competence of the country. Though there is still a long way to go, over a period of time, this system will provide employers with a pool of HR talent and raise the standard of the profession (ibid.). Since 2003, HRM professional certification has been carried out through the whole country. So far, HR profession has become one of employment permit system professions that require employees to be certified when obtaining this career in China. Now, HR professional qualification plays a more important role for those who want to engage in HR fields because of its strict process of certification for HR practitioners who have different work experiences and education backgrounds (Warner, 2011). Currently more and more people attended this certification and HR professionals have become objectives of contention due to shortage of qualified HR talents who hold the certification. Besides the HR professional qualification accreditation, there are other certifications assessed by HR professional associations in China. For instance, Human Resource Association for Chinese & Foreign Enterprises, Beijing (HRA) provides three different certifications: Practical Reward Certification, HR Business Partner Certification, Human Resource Assessor Certification, for HR practitioners at various levels. Each of the certifications in HRA has its detailed training description and course introduction. For members at different levels in HRA, they are able to choose the most appropriate certification. As such, improvement and healthy development of relevant mechanism as well as HR professional associations are crucial for the professionalization of HRM in China. Establishment of HR professional associations For the past two decades, employment agencies led by the central government and local governments represent a new institutional actor for labor relations in China. In 1995, the stated issued the Employment Agency Regulation to guide the establishment of employment agencies. The main role of these agencies is the labor dispatch even though they are criticized for their lack of professionalization, outdated market information and inability to reflect the real demand and supply in the labor market. However, too much government intervention for professional agencies might not only constrain the quality of HR services, but also hinder the professionalization of the industry. It is urgent for HRM market to establish professional associations that can relatively independently facilitate the process of professionalization of HRM in the Chinese context. Unlike developed areas such as Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development (CIPD) founded in 1913 in the UK, the Society for Human Resource Management (SHRM) founded in 1948 in US and the Hong Kong Institute of Human Resource Management (HKIHRM), professional HR associations in China are generally much less well established or independent. So far, Human Resource Association for Chinese & Foreign Enterprises, Beijing (HRA) is the only one that can be considered to be a HR professional association in the international perspective in China, which is currently an Affiliate Member of the Asia Pacific Federation of Human Resource Management (APFHRM). Facilitating the development of a harmonious relationship between the members and service providers as well as providing professional HRM training and certifications are on the listed responsibilities of HRA (HRA website, accessed on 2014). In the past two decades, HRA has experienced constant adjustment and advancement to the changing market in China and became a relatively mature HR professional association for HR practitioners. Nonetheless, compared to more advanced HR associations in Western developed countries; HRA in China is on the journey to becoming more formally recognized. For instance, HRA provides systematic information about the standards of HR practitioners, training guidance and specific courses, codes of ethics, membership requirements and certification system. As it continues to grow, the members of the association are able to form pressure groups to exert pressure on the government as it raises its public profile in a manger consistent with a professionalizing domain. Conclusion There is now clear evidence from the discussion above and findings of other studies (Law, Tse and Zhou 2003; Wei and Lau 2005; Wang, Bruning and Peng 2007), that there has been a steady rise in the level of HRM exposure and in the adoption of western imported HRM practices amongst Chinese firms (Cooke, 2011). Even though China learned a lot from Western countries about HR practices, it still developed in its own way to professionalize HR practitioners. This is especially noticeable in the demarcation in employment and HR practice that pervades the public and private sectors with exposure to foreign companies being an important mediating factor. Based on the Chinese case, this paper has reviewed the concepts of professionalization in general and HRM in particular as well as emphasizing the significance of professionalization in HR industry. This article has examined the development of professionalization of HR in China and the strategic role of the Chinese state and other actors in influencing and shaping HRM practices. It has also explored HRM professionalization policies and strategies in China and considered the means by which HR practitioners in China can be professionalized. Through analyzing professionalization of HRM in Chinese context, one gains a better understanding of the characteristics of the HR profession and certain strategies and policies issued by the state. It provides a basis for those in the research community to do further, more detailed analysis, of the dynamic interactions in the process of HRM professionalization in China. Reference: Abbott, Andrew. (2001). Chaos of Disciplines. The University of Chicago Press. Balthazard, C. (2014). The Professionalization of Human Resources. Bailey, M. (2011). Policy, professionalism, professionality and the development of HR practitioners in the UK. Journal of European Industrial Training Baker, C. R., Biondi, Y., & Zhang, Q. (2010). Disharmony in international accounting standards setting: The Chinese approach to accounting for business combinations. Critical Perspectives on Accounting, 21, 107–117 Brewster, C., Farndale, E., & van Ommeren, J. (2000). HR competencies and professional standards. Cranfield University: Centre for European Human Resource Management. Retrieved January, 24, 2004. Curnow, C. K., & McGonigle, T. P. (2006). The effects of government initiatives on the professionalization of occupations. Human Resource Management Review, 16(3), 284-293. Church, A. H. (2001). The professionalization of organization development: The next step in an evolving field. Research in organizational change and development, 13, 1-42. Collings, D., & Mellahi, K. (2009). Strategic talent management: A review and research agenda David G. Collings a,., Kamel Mellahi. Human Resource Management Review, 19, 304–313. Cooke, F. L. (2011). The role of the state and emergent actors in the development of human resource management in China. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 22(18), 3830–3848. Cooke, Fang Lee. Human Resource Management In China. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge, 2012. Print. Claus, L., & Collison, J. (2005). The maturing profession of human resources: Worldwide and regional view survey report. Society for Human Resources Management. Clark, G. J. (2008). An introduction to the legal profession in China in the year 2008. Suffolk University Law Review, 41, 833. DiMaggio, Paul, and Walter W Powell. The Iron Cage Revisited. New Haven, Conn.: Institution for Social and Policy Studies, Yale University, 1982. Eliot Freidson, (2001). Professionalism, the Third Logic. University of Chicago Press. Fanning, B. A. (2011). Human Resource Management; the Road to Professionalization in the UK and USA. Master’s thesis for Kingston University. Gao, L. (2002). What Makes a Lawyer in China-The Chinese Legal Education System after China's Entry into the WTO. Willamette J. Int'l L. & Dis. Res., 10, 197. Gerth, H. & Wright Mills, C. (Eds.). (1946). From max weber: Essays in sociology. New York: Oxford Press. Hao ZP. Regulation and organisation of accountants in China. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal (1999);12(3):286–302. Howard, A. (1995). The changing nature of work. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. Hickson D. J and Thomas M. W. (1969). Professionalization in Britain: A Preliminary Measurement. University of Aston. Hobbes, Thomas. 1651a. Leviathan. C.B Macpherson (Editor). London: Penguin Books (1985) Hoyle, E. (1974). Professionality, professionalism and control in teaching. London Educational Review, 3 (2), Summer 1974, pp.13-19. Hodson, R. and Sullivan T. A. (2012). The Social Organization of Work. Wadsworth, Cengage Learning. Howsam, R. B., Corrigan, D. C., Denemark, G. W., & Nash, R. J. (1976). Educating a profession: Report of the Bicentennial Commission on Education for the Profession of Teaching. Washington: DC: American Association of Colleges for Teachers Education. Rueschemeyer, D., & Freidson, E. (1987). Professional Powers: A Study of the Institutionalization of Formal Knowledge. Contemporary Sociology. Larson, M. S. (1979). The rise of professionalism: A sociological analysis. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. Lo, C. W. H., & Snape, E. (2005). Lawyers in the People's Republic of China: A study of commitment and professionalization. The American Journal of Comparative Law, 433-455. Millerson, G. (1964) The qualifying associations: a study in professionalization, Routledge & Kegan Paul: London. Mwita, D. (2011). Social Contract Theory of John Locke (1932-1704) in the Contemporary World. St. Augustine University Law Journal, 1(1), 49-60. Nankervis, A., Cooke, F.L., Chatterjee, S., and Warner, M. (2012), New Models of Human Resource Management in China and India, London: Routledge. Olsen, J. P. (2009). Change and continuity: an institutional approach to institutions of democratic government. European Political Science Review,1(01), 3-32. Sockett, H. (1985) Towards a Professional Code in Teaching. In P. Gordon (1985) Is Teaching a Profession? University of London, Institute of Education, 26-43. Sheldon, Peter, James Jian Min Sun, and Karin Sanders. 'Special Issue On HRM In China: Differences Within The Country'. The International Journal of Human Resource Management 25.15 (2014): 2213-2217. Thomas, S. (1996). Future trends in credentialing. In A. H. Browning, A. C. Bugbee & M.A. Mullins (Eds.), Certification: A NOCA handbook. Washington, DC: National Organization for Competency Assurance. Weiss‐Gal, I., & Welbourne, P. (2008). The professionalisation of social work: a cross‐national exploration. International journal of social welfare, 17(4), 281-290. Warner, Malcolm. 'Society And HRM In China'. The International Journal of Human Resource Management 22.16 (2011): 3223-3244. Warner, Malcolm. 'Whither Chinese HRM? Paradigms, Models And Theories'. The International Journal of Human Resource Management 23.19 (2012): 3943-3963. Yang, Baiyin, De Zhang, and Mian Zhang. 'National Human Resource Development In The People’S Republic Of China'. Advances in Developing Human Resources 6.3 (2004): 297-306. Yee, H. (2009). The re-emergence of the public accounting profession in China: A hegemonic analysis. Critical Perspectives on Accounting, 20, 71–92. Yee, H. (2012). Analyzing the state-accounting profession dynamic: Some insights from the professionalization experience in China. Accounting, Organizations