history_overheads - Rose

advertisement

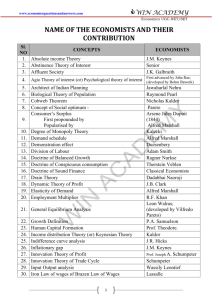

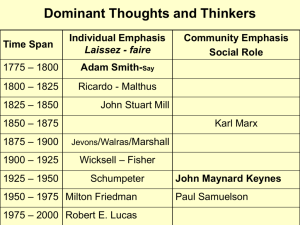

Toward the birth of Political Economy 1500 1600 1700 1800 1900 Francis Bacon 1561 - 1626 Galileo 1564 - 1642 Descartes 1596 - 1650 Thomas Hobbes 1588 - 1679 John Locke 1632 - 1704 Isaac Newton 1642 - 1727 Hobbes Locke Richard Cantillon 1680 - 1734 Frances Hutcheson 1694 - 1746 Adam Smith 1723 - 1790 David Ricardo 1772 - 1823 Smith Karl Marx 1818 - 1883 Marx Mercantilism Our ancestors took it for granted, almost throughout English history, until the mid-nineteenth century, that government should give a certain direction to national industry and commerce… Our earlier statesmen saw real merit in the old “mercantile system.” According to this system an excess in the value of exports over that of imports, and the consequent attraction, as it was assumed, of a balance in coin or bullion into the country, was a test of successful policy … Thomas Mun 1571 – 1641 Jean Baptiste Colbert 1619 – 1683 William Petty 1623 – 1687 Adam Smith first shook the principle by lucid reasonings intended to show that the “wealth of nations,” so far as that was the object in view, was best secured not by control and restrictions, but by perfect freedom of industry and commerce. Bernard Holland, The Fall of Protection, 1840 - 1850 Petty Colbert and Mercantilism Sire, it pleases Your Majesty to give some hours of his attention to the establishment, or rather the re-establishment of trade in his kingdom … As for internal trade and trade between [French] ports: The manufacture of cloths and serges and other textiles of this kind, paper goods, ironware, silks, linens, soaps, and generally all other manufactures were and are almost entirely ruined. Jean Baptiste Colbert 1619 - 1683 The Dutch have inhibited them all and bring us these same manufactures, drawing from us in exchange the commodities they want for their own consumption and re-export. If these manufactures were well reestablished, not only would we have enough for our own needs, so that the Dutch would have to pay us in cash for the commodities they desire, but we would even have enough to send abroad, which would also bring us returns in money-and that, in one word, is the only aim of trade and the sole means of increasing the greatness and power of this State. Having summarized the condition of domestic and foreign trade, it will perhaps not be inappropriate to say a few words about the advantages of trade … I believe everyone will easily agree to this principle, that only the abundance of money in a State makes the difference in its greatness and power. Memorandum to Louis XIV on trade (1664) The Physiocrats – The First Analytical Economists The land has also furnished the whole amount of moveable riches, or capitals, in existence, & these are formed only by part of its produce being saved every year. Not only does there not exist nor can there exist any other revenue than the net produce of lands, but it is also the land which has furnished all the capitals which make up the sum of all the advances of agriculture and commerce. Turgot, Reflections on the Formation and Distribution of Wealth Anne-RobertJacques Turgot 1727 - 1781 But all these items of wealth, which are successively maintained this annual product, may be destroyed or lose their value if an agricultural nation falls into a state of decline, simply though the wasting of the advances required for productive expenditure. Quesnay, Tableau Economique François Quesnay 1694 - 1774 Adam Smith and Classical Economics An Inquiry Into The Nature and Causes of The Wealth of Nations (1776) From the “Introduction and Plan of Work”: The annual labour of every nation is the fund which originally supplies it with all the necessaries and conveniencies of life which it annually consumes and which consist always either in the immediate produce of that labour, or in what is purchased with that produce from other nations. According therefore, as this produce, or what is purchased with it, bears a greater or smaller proportion to the number of those who are to consume it, the nation will be better or worse supplied with all the necessaries and conveniencies for which it has occasion. But this proportion must in every nation be regulated by two different circumstances; first by the skill, dexterity, and judgment with which its labour is generally applied; and secondly, by the proportion between the number of those who are emplolyed in useful labour, and that of those who are not so employed. David Ricardo and Classical Economics The Principles of Political Economy and Taxation (1817) From “Preface”: The produce of the earth – all that is derived from its David Ricardo 1772 - 1823 surface by the united application of labour, machinery, and capital, is divided among three classes of the community, namely, the proprietor of the land, the owner of the stock or capital necessary for its cultivation, and the labourers by whose industry it is cultivated. But in different stages of society, the proportion of the whole produce of the earth will be allotted to each of these classes, under the names of rent, profit, and wages, will be essentially different; depending mainly on the actual fertility of the soil, on the accumulation of capital, and population, and on the skill, ingenuity, and instruments employed in agriculture. To determine the laws which regulate this distribution is the principle problem in Political Economy … David Ricardo and Classical Economics The Principles of Political Economy and Taxation (1817) From Chapter 1, “On Value”: It has been observed by Adam Smith that “the word Value David Ricardo 1772 - 1823 has two different meanings, and sometimes expresses the utility of some particular object, and sometimes the power of purchasing other goods which the possession of that object conveys. The one may be called value in use; the other value in exchange …” Possessing utility, commodities derive their exchangeable value from two sources: from their scarcity, and from the quantity of labour required to obtain them … In speaking, then, of commodities, of their exchangeable value, and of the laws which regulate their relative prices, we mean always such commodities only as can be increased in quantity by the exertion of human industry, and on the production of which competition operates without restraint. Ricardo and Mill on rent It is only, then, because land is not unlimited in quantity and uniform in quality, and because, in the progress of population, land of an inferior quality … is called into cultivation, that rent is ever paid for the use of it. When, in the progress of society, land of the second degree of fertility is taken into cultivation, rent immediately commences on that of the first quality, and the amount of that rent will depend on the difference in the quality of these two portions of land. David Ricardo 1772 - 1823 Ricardo, The Principles of Political Economy and Taxation (1817) The rent of land consists of the excess of its return above the return to the worst land in cultivation. Mill, Principles of Political Economy (1848) John Stuart Mill 1806 - 1873 Economic Analysis – Key Contributors, 19th century Adam Smith (1723 – 1790) 1900 1800 David Ricardo (1772 – 1823) John Stuart Mill (1806 – 1873) Mill Karl Marx (1818 – 1883) August Cournot (1807 – 1877) Johann von Thünen (1793 – 1850) Hermann Gossen (1810 – 1858) Cournot Stanley Jevons (1835 – 1882) Leon Walras (1834 – 1910) Carl Menger (1840 – 1921) Jevons Walras Alfred Marshall (1842 – 1924) Marshall Walras’ taxonomy of science, art and ethics “Facts of the Universe” Natural Phenomena: Those which result from the blind forces of nature Pure Natural Science Human Phenomena: Those which result from the exercise of the human will (a force that is free and cognitive) Pure Moral Science Science “observes, describes, and explains” Art or Ethics Art “advises, prescribes and directs” Cournot Economists understand by the term Market, not any particular market place in which things are bought and sold, but the whole of any region in which buyers and sellers are in such free intercourse with one another that the prices of the same goods tend to equality easily and quickly A Modern Diagram Depicting of Cournot Equilibrium q1 Q a bP, Q q1 q2 a c1 1 q1* q 2 2b 2 a c2 1 q 2* q1 2b 2 . a c1 2b Competitive Outcome Cournot Outcome q1* 1 August Cournot 1803 - 1877 q 2* 2 q2 The “second generation” of marginalists Jevons saw the kettle boil and cried out with the delighted voice of a child; Marshall too had seen the kettle boil and sat down silently to build an engine. John Maynard Keynes Alfred Marshall 1842 - 1924 …The distribution of income to society is controlled by a natural law, and this law, if it worked without friction, would give to every agent of production the amount of wealth which that agent creates. Clark, Distribution of Wealth (1899) John Bates Clark 1847 - 1938 Marshall on value theory We might as reasonably dispute whether it is the upper or under blade of a pair of scissors that cuts a piece of paper, as whether value is governed by utility or costs of production. It is true that when one blade is held still, and the cutting is effected by moving the other, we may say with careless brevity that the Alfred Marshall 1842 - 1924 cutting is done by the second; but the statement is not strictly accurate, and is to be excused only so long as it claims to be merely a popular and not a strictly scientific account of what happens. Marshall, Principles of Economics (1890) Marshall on method I never read mathematics now; in fact I have forgotten how to integrate a good many things… But I know I had a growing feeling in the later years of my work at the subject that a good mathematical theorem dealing with economic hypotheses was very unlikely to be good economics: and I went more Alfred Marshall 1842 - 1924 and more on the rules – (1) Use mathematics as a shorthand language, rather than as an engine of inquiry. (2) Keep to them until you have done. (3) Translate into English. (4) Then illustrate by examples that are important to real life. (5) Burn the mathematics. (6) If you can’t succeed in (4), burn (3). Economic Analysis – Key Contributors, 20th century 2000 1900 Alfred Marshall (1842 – 1924) Thorstein Veblen (1857 – 1929) Arthur Cecil Pigou (1877 – 1959) John Maynard Keynes (1883 – 1946) Joseph Schumpeter (1883 – 1950) Schumpeter Friedrich Hayek (1889 – 1992) Milton Friedman (1912 – ) Keynes Paul Samuelson (1915 – ) Friedman James Tobin (1918 – ) Kenneth Arrow (1921 – ) Robert Solow (1921 – ) Samuelson Robert Lucas (1937 – ) Lucas Keynes and Stiglitz on Laissez Faire I abandon laissez-faire – not enthusiastically … but because, whether we like it or not, the conditions of its success have disappeared. It was a double doctrine, -- it entrusted the public weal to private enterprise unchecked and unaided. Private enterprise is no longer unchecked … And if private enterprise is John Maynard Keynes not unchecked, we cannot leave it unaided.” 1883 – 1946 The Nation (1924) Today, there is no respectable intellectual support for the proposition that markets, by themselves, lead to efficient, let alone equitable outcomes.” Forward to Karl Polanyi’s The Great Transformation (2001) Joseph Stiglitz Keynes, The General Theory -- Aggregate Demand The idea that we can safely neglect the aggregate demand function is fundamental to the Ricardian economics ... The celebrated optimum of traditional economic theory, which has led to economists being looked upon as Candide's ... is also to be traced, I think, to their having neglected to take account of the drag on prosperity which can be exercised by an insufficiency of effective demand ... It may well be that the classical theory represents the way in which we should like our Economy to behave. But to assume that it actually does so is to assume our difficulties away. The General Theory (pp. 32 – 34) Keynes, The General Theory -- The Propensity to Consume The fundamental psychological law, upon which we are entitled to depend with great confidence both a priori from our knowledge of human nature and from the detailed facts of experience, is that men are disposed, as a rule and on the average, to increase their consumption as their income increases, but not by as much as the increase in their income. That is to say, if Cw is the amount of consumption and Yw is income (both measured in wage-units) Cw has the same sign as Yw but is smaller in amount, i.e. dC w dYw is positive and less than unity. The General Theory (p. 96) Keynes, The General Theory -- Investment There will be an inducement to push the rate of new investment to the point which forces the supplyprice of each type of capital asset to a figure which, taken in conjunction with its prospective yield, brings the marginal efficiency of capital in general to approximate equality with the rate of interest. That is to say, the physical conditions of supply in the capital goods industries, the state of confidence concerning the prospective yield, the psychological attitude to liquidity and the quantity of money ... determine, between them, the rate of new investment. The General Theory (p. 248) Keynes, The General Theory -- Animal Spirits Even apart from the instability due to speculation, there is the instability due to the characteristic of human nature that a large proportion of our positive activities depend on spontaneous optimism rather than mathematical expectations, whether moral or hedonistic or economic. Most, probably, of our decisions to do something positive, the full consequences of which will be drawn out over many days to come, can only be taken as the result of animal spirits - a spontaneous urge to action rather than inaction, and not as the outcome of a weighted average of quantitative benefits multiplied by quantitative probabilities. ... if the animal spirits are dimmed and the spontaneous optimism falters, leaving us to depend on nothing but a mathematical expectation, enterprise will fade and die; The General Theory (p. 161) Keynes on economic fluctuations The “classical” view of the long-run macroeconomic adjustment process (as illustrated by the standard AS/AD model) maintains that economies, after demand and supply shocks, will naturally adjust back to full-employment or potential output. Reflecting on this belief in the underlying stability of economies, Keynes said: B . . . ut this long run is a misleading guide to current affairs. In the long run we are all dead. Economists set themselves too easy, too useless a task if in tempestuous seasons they can only tell us that when the storm is long past the ocean is flat again. Tract on Monetary Reform (1923) John Maynard Keynes (1883 – 1946) Keynesianism vs. Monetarism Keynesianism is the view that Monetarism is the view that economies are inherently unstable, that they may in fact settle at less-than full employment equilibrium, that Aggregate Demand is the primary determinant of output and employment, and that authorities can intervene in an economy to stabilize it. Keynesians generally express a preference for fiscal policy as a stabilizing tool. economies are inherently stable, that the quantity of money has a major influence on economic activity and the price level, and that the objectives of monetary policy are best achieved by targeting the rate of growth of the money supply. Monetarists generally express a preference for monetary policy as a stabilizing tool relative to prices only, being generally skeptical of attempts to manage output. Keynes Samuelson Friedman Lucas Fiscal and Monetary Policy with IS – LM analysis Typical “Keynesian” View Typical “Monetarist” View If d is “large”, IS is flat If h is “small”, LM is steep F Monetary policy is relatively strong INTEREST RATE If d is “small”, IS is steep If h is “large”, LM is flat F Fiscal policy is relatively strong INTEREST RATE (i) (i) LM LM’ Illustrating equal magnitude Shifts of IS and LM LM IS LM’ IS’ IS GNP(Y) For equal magnitude changes in fiscal or monetary policy, monetary policy is relatively more effective in influencing output. IS’ GNP(Y) For equal magnitude changes in fiscal or monetary policy, fiscal policy is relatively more effective in influencing output. Friedman on the “Chicago” school of economics In discussions of economic policy, "Chicago" stands for belief in the efficiency of the free market as a means of organizing resources, for skepticism about government affairs, and for emphasis on the quantity of money as a key factor in producing inflation. Milton Friedman (1912 – ) In discussion of economic science, "Chicago" stands for an approach that takes seriously the use of economic theory as a tool for analyzing a startlingly wide range of concrete problems, rather than as an abstract mathematical structure of great beauty but little power; for an approach that insists on the empirical testing of theoretical generalizations and that rejects alike facts without theory and theory without facts. Some Recent Nobel Laureates in Economics 2002 Daniel Khaneman Vernon Smith for having integrated insights from psychological research into economic science, and for having established laboratory experiments as a tool in empirical economic analysis. 2001 George Akerloff Michael Spence Joseph Stiglitz for their analyses of markets with asymmetric information. 1998 Amartya Sen for his contributions to welfare economics. 1994 John Harsanyi John Nash Reinhard Selten for their pioneering analysis of equilibria in the theory of non-cooperative games. 1993 Robert Fogel Douglass North for having renewed research in economic history by applying economic theory and quantitative methods in order to explain economic and institutional change. 1992 Gary Becker for having extended the domain of microeconomic analysis to a wide range of human behaviour and interaction. Economic Methodology – The “Deductive” Approach The propositions of economic theory, like all scientific theory, are obviously deductions from a series of postulates … These are not postulates the existence of whose counterpart in reality admits of extensive dispute once their nature is fully realized. We do not need controlled experiments to establish their validity: they are so much the stuff of our everyday experience that they have only to be stated to be recognized as obvious. An Essay on the Nature and Significance of Economic Science (1935) Lionel Robbins Economic Methodology – The “Modernist” Approach The ultimate goal of a positive science is the development of a “theory” or “hypothesis” that yields valid and meaningful predictions about phenomena not yet observed … Factual evidence can never “prove” a hypothesis; it can only fail to disprove it, which is what we generally mean when we say, somewhat inexactly, that the hypothesis has been “confirmed” by experience … Milton Friedman … the relevant question to ask about the “assumptions” of a theory is not whether they are descriptively “realistic,” for they never are, but whether they are sufficiently good approximations for the purpose in hand. And this question can be answered only by seeing whether the theory works, Which means whether it yields sufficiently accurate predictions. The Methodology of positive economics (1953) Economic Methodology – The “Functional” Approach The view that the worth of a theory is to be judged solely by the extent and accuracy of its predictions seems to me wrong ... a theory is not like an airline or bus timetable We are not interested simply in the accuracy of its predictions. A theory also serves as a base for thinking. It helps us to understand what is going on by enabling us to organize our thoughts. Faced with a choice between a theory which predicts well but gives us little insight into how the system works and one which gives us this insight but predicts badly, I would choose the latter, and I am inclined to think that most economists would do the same. How Should Economists Choose? (1981) Ronald Coase Economists on Economic Methodology – Selected References John Stuart Mill, “On the definition and method of political economy” (1836) Henry Sidgewick, “The scope and method of economic science” (1885) Thorestein Veblen, “Why is economics not an evolutionary science?” (1898) Lionel Robbins, “The nature and significance of economic science” (1935) Milton Friedman, “The methodology of positive economics” (1956) James Buchanan, “What should economists do?” (1964) Donald McCloskey, “The rhetoric of economics” (1983) Ronald Coase, “How should economists choose?” (1994)