File - Lets have some fun:)

advertisement

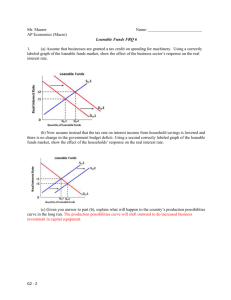

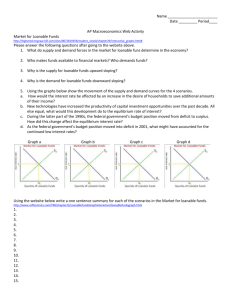

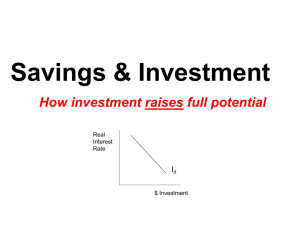

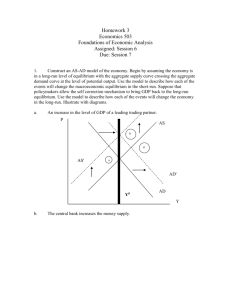

9.1 The Basics of Economic Growth Calculating Growth Rates The economic growth rate is the annual percentage change of real GDP. The growth rate of real GDP equals: (Real GDP in current year - Real GDP in previous year) 100. (Real GDP in previous year) The standard of living depends on real GDP per person, which is real GDP divided by the population. The growth rate of real GDP per person equals: Growth rate of real GDP per person = Growth rate of real GDP – Growth rate of population. The growth rate of real GDP per person can also be measured as (Real GDP per person in current year - Real GDP per person in previous year) 100. (Real GDP per person in previous year) The Magic of Sustained Growth 9.2 The Rule of 70 demonstrates the magic of economic growth. The Rule of 70 states that the number of years it takes for the level of any variable to double is approximately 70 divided by the annual percentage growth rate of the variable. The Sources of Economic Growth The factors that influence real GDP growth can be divided into those that change the quantity of labor and those change labor productivity. Our standard of living improves only if growth occurs because of increases in labor productivity. Quantity of Labor The quantity of labor is the total number of labor hours available and equals the labor force multiplied by average hours per worker. Average hours worked have decreased though increases in the population and labor force participation rate have caused the labor force to grow fast enough to bring about sustained increases in the quantity of labor. Population growth is the only source of growth in the quantity of labor that can be sustained over long periods. However although population growth causes economic growth, it does not increase real GDP per person. Labor Productivity 9.3 Labor productivity is the quantity of real GDP produced by one hour of labor. Labor productivity = (Real GDP) (Aggregate hours). o Rearranging, real GDP = (Aggregate hours) (Labor productivity). Using the rearranged formula shows that growth in real GDP can be divided into growth in aggregate hours and growth in labor productivity. Three factors influence the growth of labor productivity: Saving and investment in physical capital: More saving and investment in physical capital increases labor productivity. Expansion of human capital: Human capital is the accumulated skills and knowledge of people. Increases in human capital increase labor productivity. Discovery of new technologies: New technologies increase labor productivity. Often these new technologies require new capital, such as personal computers replacing typewriters. Theories of Economic Growth Classical Growth Theory Classical growth theory is the theory that the clash between an exploding population and limited resources will eventually bring economic growth to an end. Malthusian theory is another name for classical growth theory—named after Thomas Robert Malthus. Malthus predicted that population growth would result in people having a primitive standard of living at the subsistence level of real GDP per person. The basic idea is that economic growth raises GDP per person but induces a population explosion, which eventually ends the prosperity. In more detail: An increase in productivity—for whatever reason—increases the demand for labor and increases the real wage rate. The economy has grown. But when the real wage rate rises it exceeds the subsistence real wage rate—that, is real GDP per person exceeds the subsistence real GDP per person—the population grows. Population growth increases the supply of labor, which lowers the real wage back to its subsistence level. Economic growth ceases. The classical theory of growth takes technological change as exogenous, essentially ignores the role of capital (as a result of the era in which it was developed), and assumes that population growth increases when income increases Neoclassical Growth Theory Neoclassical growth theory is the theory that real GDP per person will increase as long as technology keeps advancing. o Neoclassical theory follows the classical theory by taking technological growth as exogenous. It differs insofar as it assumes that population growth also is exogenous. The basic idea is that prosperity (high real GDP per person) will last but economic growth (growth in real GDP per person) will not, unless technology keeps advancing. Population growth does not play a role in the neoclassical theory because the historical population trends contradict the view of the classical economists about population growth: Higher income does not lead to a population boom and an increase in the supply of labor. The neoclassical theory emphasizes that technological change influences the rate of economic growth but not vice versa. Technological change results from chance. But a problem with neoclassical growth theory is that the theory does not explain what determines technological change. New Growth Theory New growth theory is the theory that our unlimited wants will lead us to ever greater productivity and perpetual economic growth. o Neoclassical theory also is incomplete because the primary engine of economic growth, technology, is exogenous. New growth theory attempts to overcome this weakness. It still uses many of the insights of the neoclassical theory by emphasizing the role of capital accumulation and assuming that population growth is exogenous. But, the new growth theory builds on neoclassical theory by examining more closely the role of technology and the factors that influence technological advances. The new growth theory emphasizes the role played by choices and innovation. In particular, it emphasizes three key aspects of market economies: Human capital grows because of choices. Discoveries result from choices. Discoveries bring profit, and competition destroys profit. Once a new discovery has been made, it can be used by everyone. In addition, production activities can be replicated so that identical firms can each produce the same quantity of an item and so the economy does not suffer from diminishing returns. A new discovery shifts the production function upward and increases labor productivity and the demand for labor. The equilibrium quantity of employment rises. So real GDP grows 9.4 because the production function shifts upward and because the quantity of employment increases. Economic growth is driven by insatiable wants, which lead us to pursue profit and to innovate. The new and better products mean that old firms go out of business. New firms start up, which creates new and better jobs and leads to greater consumption and leisure. But insatiable wants simply start the growth cycle all over again. Achieving Faster Growth Preconditions for Economic Growth Three necessary preconditions for economic growth are: Economic freedom: Economic freedom is a condition in which people are able to make personal choices, their private property is protected, and they are free to buy and sell in markets. Property rights: Property rights are the social arrangements that govern the protection of private property. Clearly established and enforced property rights provide people with the incentive to work and save. Markets: Markets enable people to trade and to save and invest. Markets cannot operate without property rights. These three preconditions for economic growth are necessary for growth but do not guarantee that economic growth will occur. For growth to occur and to persist, people need incentives to save and invest, to accumulate human capital, and to develop new technologies. Policies to Achieve Faster Growth 10.1 Government policies to achieve economic growth must provide people with the incentives to save and investment, accumulate human capital, and develop new technologies. Create Incentive Mechanisms: Enforce property rights with a well-functioning legal system. (lowers the cost of enforcing property rights) Encourage Saving: Increased saving can increase the growth of capital and stimulate economic growth. This process takes place through financial institutions in markets for financial capital. Encourage Research and Development: More research and development creates technological advances. Governments can direct public funds toward financing basic research. Encourage International Trade: International trade extracts all the available gains from specialization and exchange. Improve the Quality of Education: The social benefits of education go beyond the benefits accrued to the individuals who receive the education. The government can help by financing more basic education to raise skills in language, math and science. Financial Institutions and Markets Some Finance Definitions Finance is the lending and borrowing that moves funds from savers to spenders. Money is the object (or objects) that people use to make payments. Physical capital is a long lived good, which is itself used to produce other goods and services (tools, instruments, machines and buildings are all forms of physical capital) Financial capital is the funds firms use to buy and operate physical capital. (Stocks bonds and short-term securities are all forms of financial capital.) o Investment increase the quantity of capital and depreciation decreases it. Gross investment is the total amount spent on new capital goods. Net investment equals gross investment minus depreciation. The change in the quantity of capital is net investment. Wealth is the value of all the things that a person owns. o Saving is the amount of income that is not paid in taxes or spent on consumption goods and services. Saving adds to wealth. Wealth also increases when the market value of assets rises – called capital gains. o Economist have identified 3 reasons for why people might save: Life-cycle savings (people may save to meet long term objectives) Precautionary saving (savings to protect against an unexpected set back) Bequest savings (savings done for the purpose of leaving an inheritance) To make real GDP grow, saving and wealth must be transformed into investment and capital. This process takes places through financial institutions in markets for financial capital. Market for Financial Capital Savings finances investment in the three types of financial markets: Loan Markets: Loans from banks are a way firms finance their short-term capital needs and how households get funds to buy new homes. Bond Markets: A bond is a promise to pay specified sums of money on specified dates and is a debt for the issuer of the bond. Firms and governments sell bonds to raise funds. The bond market is the financial market in which bonds issued by firms and governments are traded. o Firms often issue short-term bonds as a way of getting paid for their sales before the buyer is able to pay. Treasury bills are short-term bonds issued by the U.S. Treasury. Mortgage-backed securities, which were at the center of the 2007-2008 financial storm, are bonds that entitle the holder to the income from a package of mortgages. Stock Markets: A stock is a certificate of ownership and claim to the profits that a firm makes. A stock market is a financial market in which shares of companies’ stocks are traded. Examples include the New York Stock Exchange, the NASDAQ, the London Stock Exchange, the Frankfurt Stock Exchange, and the Tokyo Stock Exchange. Financial Institutions A financial institution is a firm that operates on both sides of the markets for financial capital: It borrows in one market and lends in another. The key financial institutions are: Investment banks: firms that help other financial institutions and governments raise funds by issuing and selling bonds and stocks, as well as providing advice on transactions such as mergers and acquisitions. Commercial banks: provide banking services (such as accepting deposits and making loans) and issue credit cards. Government-sponsored mortgage lenders: buy mortgages from banks, package them into mortgage-backed securities, and sell them. Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac are two governmentsponsored mortgage lenders that were taken over by the federal government in September 2008. Pension funds: use the pension contributions of firms and workers to buy bonds and stocks. Insurance companies: enter into agreements with households and firms to provide compensation in the event of misfortunate (accident, theft, fire, ill-health, firm failure, etc). Insurance companies receive premiums from their customers, make payments against claims, and use the excess funds to buy bonds and stocks on which they earn interest. Profit is the gap between the incoming flow of funds from premiums and interest and the outgoing flow of funds from paying claims, which can turn negative. With large and widespread losses it can be difficult for the insurer to meet their obligations. Insolvency and Illiquidity A financial institution’s net worth is the total market value of what it has lent minus the market value of what it has borrowed. If the net worth is positive, the institution is solvent and can remain in business. If the net worth is negative, the institution is insolvent and must stop trading. A firm is illiquid if it has made long-term loans with borrowed funds and is faced with a sudden demand to repay more of what it has borrowed than is available in cash. Normally, an illiquid financial institution can borrow from another institution, though this becomes difficult if all financial institutions are short on cash. Insolvency and illiquidity were at the core of the 2007-2008 financial meltdown. Interest Rates and Asset Prices Stocks, bonds, short-term securities, and loans are collectively called financial assets. The interest rate on a financial asset is a percentage of the price of an asset. There is an inverse relationship between an asset price and interest rate. 10.2 The Market For Loanable Funds Flows in the Market for Loanable Funds Loanable funds are used for business investment, government budget deficit, and international investment or lending. These are the sources of demand for loanable funds. Loanable funds come from private saving, government budget surplus, and international borrowing. These are the sources of supply of loanable funds. The Demand for Loanable Funds The demand for loanable funds is the demand to finance business investment, government budget deficit, and international investment or lending. The largest source of these is the demand to finance investment so it dominates the demand for loanable funds. Investment depends on two factors: the real interest rate and expected profit. Firms invest only when the expected profit rate exceeds the real interest rate. Investment is inversely related to the real interest rate. So, other things remaining the same, the higher the real interest rate, the smaller is the quantity of loanable funds demanded; and the lower the real interest rate, the greater is the quantity of loanable funds demanded. The demand for loanable funds is the relationship between the quantity of loanable funds demanded and the real interest rate, other things remaining the same. As illustrated in the figure, the demand for loanable funds curve is downward sloping, showing the negative relationship between the real interest rate and the quantity of loanable funds demanded. A change in expected profit changes the demand for loanable funds and shifts the demand for loanable funds curve. An increase in expected profit increases investment. The demand for loanable funds increases and the demand for loanable funds curve shifts rightward. You should be able to determine if someone will or will not choose to invest based on the expected interest rate. o Ex: If Larry wants to open a bakery he will have to buy a $4,000 oven by taking out a loan at 6 percent annual interest. With the oven he can net $6,000 dollars (after the deduction of costs such as flour and other ingredients etc.). Of the $6,000 in net revenue, 20 percent must be paid in taxes. If you assume that Larry could make $4,400 after taxes if he stayed at his old job, should Larry open the business? To solve you would compare the benefits from opening the business to the costs. The marginal value of opening the business is $400 per year. The cost of the business is the interest on the oven (assuming that the oven does not lose value o over time) which is equal to $240 per year. Since the benefits exceed the cost, he should open the business. As the real interest rate increases, it is less likely that expected benefits will exceed expected costs. Supply of Loanable Funds The supply of loanable funds is the supply from private saving, government budget surplus, and international borrowing. The largest source of these is from private saving so it dominates the supply of loanable funds. Saving depends on the real interest rate, disposable income, wealth, expected future income, and default risk. Saving is positively related to the real interest rate. So, other things remaining the same, the higher the real interest rate, the greater is the quantity of loanable funds supplied; and the lower the real interest rate, the smaller is the quantity of loanable funds supplied. The supply of loanable funds is the relationship between the quantity of loanable funds supplied and the real interest rate, other things remaining the same. As illustrated in the figure, the supply of loanable funds curve is upward sloping, showing the positive relationship between the real interest rate and the quantity of loanable funds supplied. A change disposable income (income minus net taxes); a change in wealth; a change in expected future income; and a change in default risk (the risk that a loan will not be repaid) change the supply of loanable funds and shift the supply of loanable funds curve. o A decrease in disposable income, an increase in wealth, an increase in expected future income, positive inflation expectations, a decrease in the liquidity of savings and a greater default risk all decrease saving. The supply of loanable funds decreases and the supply of loanable funds curve shifts leftward. Equilibrium in the Market for Loanable Funds The loanable funds market is in equilibrium when the real interest rate is such that the quantity of loanable funds supplied equals the quantity of loanable funds demanded. There is neither a surplus nor a shortage of saving so that borrowers can get the funds they demand and lenders can lend all the funds they have available. In the figure, the equilibrium real interest rate is 6 percent and the equilibrium quantity of loanable funds is $2.0 trillion. If the demand for loanable funds increases, perhaps because of an increase in expected profit that increases investment, the demand for loanable funds curve shifts rightward. The equilibrium real interest rate rises and the equilibrium quantity of loanable funds increases. If the supply of loanable funds increases, perhaps because of an increase in disposable income that increases saving, the supply of loanable funds curve shifts rightward. As the figure shows, the equilibrium real interest rate falls (from 6 percent to 4 percent in the figure) and the equilibrium quantity of loanable funds increases (from $2.0 trillion to $2.5 trillion in the figure). 10.3 Government in Loanable Funds Market A Government Budget Surplus Government savings = T-G A government budget surplus (T>G)increases the supply of loanable funds. With the increase in the supply of loanable funds, the real interest rate falls, which decreases private savings and decreases the quantity of private loanable funds supplied (that is, there is a movement along the price supply of loanable funds curve). The lower real interest rate increases the quantity of loanable funds demanded and increases investment. In the figure, the private supply of funds curve is labeled PSLF. The government budget surplus is equal to $1 trillion, which is the length of the double-headed arrow. The total supply of loanable funds is the sum of private supply of loanable funds plus government budget surplus. The supply of loanable funds curve is labeled SLF in the figure. The government budget surplus lowers the equilibrium real interest rate from 6 percent to 4 percent and increases the equilibrium quantity of loanable funds from $2.0 trillion to $2.5 trillion. Because of the lower real interest rate, the quantity of private loanable funds, that is, the quantity of private saving, decreases by $0.5 trillion. A Government Budget Deficit 11.1 A government budget deficit (G>T) increases the demand for loanable funds. The real interest rate rises, which increases private savings and increases the quantity of private loanable funds supplied. The higher real interest rate decreases investment and the quantity of loanable funds demanded by firms to finance investment. The tendency for a government budget deficit to raise the real interest rate and decrease investment is called the crowding-out effect. Ricardo-Barro effect says that a government deficit leads rational taxpayers to expect higher future taxes and lower disposable incomes, thereby causing them to increase current saving. Private saving and the private supply of loanable funds offset the deficit. As a result, the real interest does not change and investment is not crowded out. While private savings may change in the direction predicted by the Ricardo-Barro effect to lessen the influence of the budget deficit on investment and the real interest rate, most economists agree that a full Ricardo-Barro effect is unlikely. You should feel comfortable finding the equilibrium in the loanable funds market, showing the value of the crowding out effect, government deficit / surplus, quantity of loanable funds demanded quantity of loanable funds supplied and the real interest rate using a graph or table. What Is Money? Money is any commodity or token that is generally acceptable as a means of payment. A means of payment is a method of settling a debt. Money has three functions: Medium of exchange: A medium of exchange is any object that is generally accepted in exchange for goods and services. Money acts as a medium of exchange. As a result, money eliminates the need for barter, which is the exchange of goods and services directly for other goods and services. Barter requires a double coincidence of wants. Unit of account: Money serves as a unit of account, which is an agreed-upon measure for stating the prices of goods and services Store of value: Money serves as a store of value, which is any commodity or token that can be held and exchanged later for goods and services. Money Today Commodity money refers to money whose value comes from the commodity from which it is made(gold coins would be an example of commodity money). Fiat money refers to money whose value comes from the fact that the law decrees or orders them to be money. Today’s fiat money consists of currency (the bills and coins that we use in the United States today) and deposits at banks and other depository institutions. Deposits are money because they can be converted into currency and because they are used to settle debts. Currency in a bank is not counted as money; only currency held by individuals and businesses in any form is counted money. Credit cards are not money—they are IDs that allow an instant loan Checks, e-checks, and debit cards are not money—they are instructions to a bank to transfer money from one person to another. E-cash operates similarly to paper notes and coins, but doesn’t yet meet the definition of money. However, as it becomes more widely accepted it will likely gradually replace physical forms of currency. Official Measures of Money: M1 and M2 M1 consists of currency held by individuals and businesses and traveler’s checks plus checkable deposits owned by individuals and businesses. M2 consists of M1 plus savings deposits, small time deposits, and money market mutual funds and other deposits. M2 is much larger than M1, $8,298 billion versus $1,650 billion in September 2009. M2 includes liquid assets that are not means of payment. 11.2 The Banking System The banking system consists of the Federal Reserve and the banks and other institutions that accept deposits. There are three types of depository institutions whose deposits are money: commercial banks, thrift institutions, and money market mutual funds. Commercial Banks A commercial bank is a firm that is chartered by the Comptroller of the Currency or by a state agency to receive deposits and make loans. The number of commercial banks in the U.S. has shrunk dramatically in the past decade due to mergers and failures. A commercial bank accepts checkable deposits, savings deposits, and time deposits. A commercial bank tries to maximize their stockholders’ wealth by lending for long terms at high interest rates and borrowing from depositors and others. Banks must be careful to balance security for depositors and stockholders against high but risky returns from loans. To tradeoff between risk and profit a bank divides its assets into: Balance sheet for all commercial banks ASSETS (Uses of funds) Liabilities (Sources of funds) Reserves & cash items Checkable Deposits Securities Non-transaction deposits (time deposits or savings deposits) Loan Borrowing (from Fed reserve bank of other banks) Other assets Bank Capital (example: physical capital) You should know how the bank’s balance sheet changes when deposits are made. (Will be included in liabilities as a deposit and under assets as a reserve) Reserves. A bank’s reserves are its currency in its vault plus the balance on its reserve account at a Federal Reserve Bank. The required reserve ratio is the ratio of reserves to deposits that banks are required, by regulation, to hold. Liquid Assets. Liquid assets are short-term Treasury Bills and overnight loans to other banks – these assets how have low interest rates and low risk. The federal funds rate is the interest rates on interbank loans and is the central target for monetary policy. Securities and loans. Banks buy securities issued by the U.S. government and large businesses. Some securities have low interest rates and low risk, while others have high interest rates and high risk. Banks also make loans to businesses and individuals. Loans tend to have higher interest rates and high risk and cannot be recalled until the agreed date. Thrift Institutions The thrift institutions are savings and loan associations, savings banks, and credit unions. A saving and loan association (S&L) is a financial institution that receives checking deposits and savings deposits and that makes personal, commercial, and home-purchase loans. A savings bank is a financial institution that accepts saving deposits and makes mostly mortgage loans. A credit union is a financial institution owned by a social or economic group such as a firm’s employees that accepts savings deposits and makes mostly consumer loans. Money Market Mutual Funds A money market mutual fund is a fund operated by a financial institution that sells shares in the fund and holds liquid assets such as U.S. Treasury bills or short-term commercial debt. Shareholders can write checks of large amounts (for instance, a $500 minimum) on a money market mutual fund account. 11.3 The Federal Reserve System The central bank of the United States is the Federal Reserve System. A central bank is a public authority that provides banking services to banks and regulates financial institutions and markets. The Structure of the Federal Reserve The Board of Governors has seven members who are appointed by the President and confirmed by the Senate to 14 year, nonrenewable terms. One of the members is appointed by the President to act as the Chairman (a 4 year, renewable position). There are 12 regional Federal Reserve banks. The Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) is the Fed’s main policy-making committee that meets approximately every 6 weeks. It is comprised of the members of the Board of Governors and the Presidents of the regional Federal Reserve Banks. The Board of Governors, the President of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, and, on a rotating basis, the presidents of four other regional Federal Reserve Banks, vote on monetary policy. In practice, the chairman has the largest influence on policy. The Fed’s Policy Tools Required reserve ratios: The minimum percentage of deposits that depository institutions must hold as reserves are the required reserve ratios. The Fed sets the required reserve ratios. Discount rate: The discount rate is the interest rate at which the Fed stands ready to lend reserves to depository institutions. Open market operation: An open market operation is the purchase or sale of government securities by the Federal Reserve System in the open market. The Fed does not directly purchase bonds from the federal government because it would appear that the government was printing money to finance its expenditures. Extraordinary crisis measures: In response to the 2008 financial crisis, the Fed created new policy tools that can be grouped into two broad categories: Quantitative easing: when the Fed creates bank reserves by a large scale open market operation at a low or possibly zero interest rate in the federal funds market. Credit easing: when the Fed buys private securities or makes loans to financial institutions to stimulate their lending. How the Fed’s Policy Tools Work The monetary base is the sum of coins, Federal Reserve notes, and banks’ reserves at the Fed. It is by changing the monetary base that the Fed can change the quantity of money in the economy. By increasing the required reserve ratio, the Fed forces banks to hold more reserves, which are part of the monetary base. This action decreases the quantity of money. By raising the discount rate, the Fed discourages banks from borrowing reserves, which decreases the quantity of money. By selling securities in the open market, the Fed decreases the monetary base, which decreases the quantity of money. 11.4 Regulating the Quantity of Money Creating Deposits by Making Loans Commercial banks use their excess reserves to make loans to the public. When a borrower is granted a loan, the bank gives the borrowers the funds by creating a checkable deposit in the borrower’s name and depositing the amount loaned in the account. Therefore making loans is how banks create (deposit) money. The monetary base limits the total quantity of money the banking system can create. The monetary base is held by the public as currency and as banks as reserves, so the monetary base limits the amount of banks’ reserves. A bank’s desired reserves are is the amount of reserves a bank wants to hold. Excess reserves equal actual reserves (currency in the bank’s vault plus its deposit at the Fed)—minus its desired reserves. Banks can lend their excess reserves, so excess reserves can be used for money creation. The public holds some proportion of its money as currency. Currency held by the public cannot be used as reserves and hence is a leakage of reserves from the banking system. The ratio of currency to deposits is the currency drain ratio. How Open Market Operations Change the Monetary Base When the Fed buys government securities in an open market operation, banks’ excess reserves increase. As a result, banks increase their lending and the quantity of money increases. To decrease the quantity of money, the Fed sells government securities in the open market. Whether the Fed buys (or sells) from a bank or a member of the non-bank public makes no difference. The Multiplier Effect of an Open Market Operation An open market purchase by the Fed of government increases banks’ reserves and also increases the monetary base (the sum of Federal Reserve notes plus banks’ reserves at the Fed) by the amount of the purchase. For each dollar deposited, a bank keeps a fraction as reserves and lends out the rest. Excess reserves give a single bank the ability to make loans. When a bank makes a loan, it creates a new deposit (new money) equal to the value of the loan. After the loan is spent by the borrower, the new money eventually ends up back as a new deposit in a bank. As new deposits are made, the process of money creation begins again, albeit with a smaller amounts each time because banks keep a fraction of each deposit in the form of reserves. A change in the monetary base has a multiplied effect on the quantity of money because banks’ loans are deposited in other banks where they are loaned once again. Deposits Desired reserves Loans Total increase in the quantity of money $1,000 $1,000 $100 $900 $1,000 2 900 900 90 810 1,810 3 810 810 81 729 2,539 Round Total reserves 1 The table above shows 3 rounds of the multiplier effect. The Fed makes an initial $1,000 purchase of government securities from a member of the nonbank public, which increases the bank’s total reserves by $1,000 and deposits by $1,000. The desired reserve ratio is 10 percent and the bank wants to hold no excess reserves. The currency drain is 0 percent. So in the first round the bank loans its excess reserves of $900, which are then the deposits of the second round. The third round is similar. The last column is running tally of the increase in the quantity of money. In the case in this table, the ultimate increase will be $10,000. An increase in currency held outside the banks, the currency drain, decreases the amount of money that banks can create from a given increase in the monetary base. The Money Multiplier The money multiplier is the number by which a change in the monetary base is multiplied to find the resulting change in the quantity of money. It determines the change in the quantity of money that results from a given change in the monetary base. The larger the currency drain, the smaller the money multiplier. (1 C ) , where C is the currency drain and R is the desired reserve The money multiplier equals ( R C) ratio. The currency drain is the ratio of currency kept outside of banks to deposits. 12.1 To derive the money multiplier, Reserves = R Deposits, and Currency = C Deposits. The monetary base, or MB, equals Reserves + Deposits, so MB = R Deposits + C Deposits. As a result, MB = (R + C) Deposits. The quantity of money, M equals Deposits + Currency, so M = Deposits + C Deposits, so that M = (1 + C) Deposits. (1 C ) Divide M by MB and then multiply by MB to get M = MB. ( R C) Money and the Interest Rate Real factors, which are independent of the price level, determine potential GDP. Changes in the quantity of money have no effect on potential GDP. The immediate impact and long-run impact of a change in the quantity of money are studied in this chapter. The intermediate impacts are studied in the next section of the book. The Demand for Money The demand for money refers to the amount of money that households and firms choose to hold, not to the desire to receive money. The quantity of money that people plan to hold depends on the nominal interest rate because the nominal interest rate is the opportunity cost of holding money. An increase in the nominal interest rate decreases the quantity of real money demanded. The Demand for Money Curve The demand for money is the relationship between the quantity of money demanded and the nominal interest rate, when all other influences on the amount of money people wish to hold remain the same. A demand for money curve is plotted in the figure. As the figure shows, there is a negative relationship between the interest rate and the quantity of money demanded. Changes in the Demand for Money A change in the nominal interest rate changes the quantity of money demanded and there is a movement along the demand for money curve. Changes in factors that affect the demand for money other than the nominal interest rate change the demand for money and the demand for money curve shifts. These factors are: The price level: The quantity of money demanded is proportional to the price level so that, for example, when the price level doubles, the quantity of dollars demanded doubles. The demand for money curve shifts rightward. Real GDP: An increase in real GDP increases the quantity of money people plan to hold so that they can make the increased expenditures. The demand for money curve shifts rightward. Financial technology: Some financial innovation decreases the quantity of money people plan to hold (credit cards) and other financial innovation increases it (interest paid on checking accounts). The Supply of Money The supply of money is the relationship between the quantity of money supplied and the nominal interest rate. Any given day the quantity of money supplied is fixed, so the supply of money curve is vertical at this quantity. Interest Rate Determination An interest rate is the percentage yield on a financial security such as a bond or a stock. There is an inverse relationship between the price of the security and the interest rate. The interest rate is determined by the supply of money and the demand for money. The equilibrium interest rate equates the quantity of real money demanded with the (fixed) quantity of real money supplied. In the figure, the equilibrium nominal interest rate is 5 percent. Changing the Interest Rate By changing the quantity of money in the economy, the Fed is able to influence the interest rate. If the Fed decreases the quantity of money, say by an open market operation in which the Fed sells government securities, the quantity of money decreases and the supply of money curve shifts leftward, as illustrated in the figure by the shift from MS0 to MS1. As a result, the equilibrium interest rate rises, from 5 percent in the figure to 7 percent. If the Fed increases the quantity of money, the interest rate falls