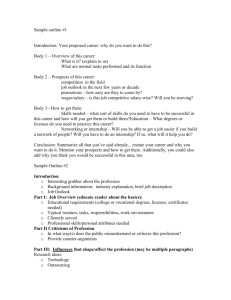

Legal Profession Act 2004

advertisement

The Legal Profession Topic 4 Lecture outline Now a (semi) national profession How was this achieved? What are the obligations of members of the profession? Development of Profession English legal profession develops to serve developing courts Attorneys and pleaders Development of Inns of Court Practical focus of training Solicitors – commercial focus The Compleat Solicitor 1683 Scale costs: will And in Australia….. State based profession State based admission Why? NSW Originally split profession Victoria ‘fused’ Reform of Australian profession Law Council of Australia: Blueprint for the Structure of the Legal Profession: A National Market for Legal Services. Mutual Recognition Act 1992 (Cth) Referral of powers S51(xxxvii) matters referred to the Parliament of the Commonwealth by the Parliament or Parliaments of any State or States, but so that the law shall extend only to States by whose Parliaments the matter is referred, or which afterwards adopt the law MUTUAL RECOGNITION (NEW SOUTH WALES) ACT 1992 - SECT 4 (1) The following matters, to the extent to which they are not otherwise included in the legislative powers of the Parliament of the Commonwealth, are referred to the Parliament of the Commonwealth for a period commencing on the day on which this Act commences and ending on the day fixed under subsection (4) as the day on which the reference under this Act terminates, but not longer, namely, the matters to which the Schedule relates but only to the extent of: (a) the enactment of an Act in the terms, or substantially in the terms, set out in the Schedule, and (b) the amendment of that Act (other than the Schedules), but only in terms which are approved by the designated person for each of the then participating jurisdictions. (2) For the purposes of this section, a "participating jurisdiction" is: (a) a State for which there is in force an Act of its Parliament that refers to the Parliament of the Commonwealth the matters mentioned in subsection (1), or that adopts the Commonwealth Act, under paragraph (xxxvii) of section 51 of the Commonwealth Constitution , or (b) a Territory (being the Australian Capital Territory or the Northern Territory) for which there is in force an Act of its legislature that requests the Parliament of the Commonwealth to enact the Commonwealth Act or that enables the Commonwealth Act to apply in relation to it. .... (4) The Governor may, at any time, fix by proclamation published on the NSW legislation website a day as the day on which the reference under this Act terminates. Common admission Legal Profession Reform Act 1993 (NSW) Moves towards admission as an Australian lawyer, rather than State based admission SCAG reference 2001 – COAG process Legal Profession Act 2004 (NSW) Australian lawyer Section 5 of the LEGAL PROFESSION ACT 2004 (NSW) tells us that: “an "Australian lawyer" is a person who is admitted to the legal profession under this Act or a corresponding law,” Towards a national profession September 2011 – agreement reached by NSW, Victoria, Qld and NT Legal Profession National Law Agreed draft legislation Application Scheme Victoria – host legislation 1.1.2 Commencement This Law commences in a jurisdiction as provided by the Act of that jurisdiction that applies this Law as a law of that jurisdiction. Objectives ...promote the administration of justice and an efficient and effective Australian legal profession, by: (a) ...national consistency... (b) ensuring lawyers are competent and maintain high ethical and professional standards in the provision of legal services; and (c) ...protection of clients ...and the ...public... (d) ...nformed choices about [legal] ...services... (e) promoting regulation of the legal profession that is efficient, effective, targeted and proportionate; and (f) providing a co-regulatory framework within which an appropriate level of independence of the legal profession from the executive arm of government is maintained. Where are we now? Victoria will host legislation NSW will host National Legal Services Board and National Legal Services Commissioner Implementation goal: July 2013 Legal Profession Uniform Law Application Bill was passed by the Victorian Parliament on 13 March 2014. Where are we now? Note name change Australian Solicitor’s Conduct Rules SA and Qld – no other jurisdiction http://www.lawcouncil.asn.au/shadomx/apps/fms/fmsdownload.cfm?file_uuid=D997CD5392D0-1795-82F7-5436F67E9BCD&siteName=lca October 2012 Qld government withdraws support http://statements.qld.gov.au/Statement/2012/10/3/queensland-not-signing-up-to-nationallegal-profession-reform De Jersey CJ speech: http://www.hearsay.org.au/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=782&Itemid=4 NSW Legal Profession Uniform Law Application Bill 2014 passed 13 May Assented on 20/05/2014 - Act No 16 of 2014 http://www.parliament.nsw.gov.au/prod/p arlment/NSWBills.nsf/1d436d3c74a9e047c a256e690001d75b/07eb41c6b04dca11ca2 57ca600183bba?OpenDocument Second reading speech http://www.parliament.nsw.gov.au/prod/p arlment/NSWBills.nsf/1d436d3c74a9e047c a256e690001d75b/07eb41c6b04dca11ca2 57ca600183bba/$FILE/2R%20Legal.pdf 4 Application of Legal Profession Uniform Law The Legal Profession Uniform Law set out in Schedule 1 to the Legal Profession Uniform Law Application Act 2014 of Victoria: (a) applies as a law of this jurisdiction, and (b) as so applying may be referred to as the Legal Profession Uniform Law (NSW), and (c) so applies as if it were an Act. Legal Profession Uniform Law Repeals Legal Profession Act 2004 Australian Practising Certificate Retains role of NSW Admission Board (LBAB) Retains role of NSW professional societies Maintains common admission but functional separation of earlier Legal Profession Reform Act 1993 (NSW) Role of professional societies LEGAL PROFESSION UNIFORM LAW APPLICATION ACT 2014 s29 – Bar Association s31 – Law Society of NSW Exercise powers under the Act and as a delegate of the NSW Legal Services Commissioner Legal Profession Uniform Law 419 Power to make Uniform Rules (1) The Council may make Legal Profession Uniform Rules with respect to any matter that by this Law is required or permitted to be specified in Uniform Rules or that is necessary or convenient to be specified for carrying out or giving effect to this Law. NSW Bar Association NSW Bar Rules http://www.nswbar.asn.au/docs/webdocs/ rules2.pdf These Rules are made in the belief that: (a) barristers owe their paramount duty to the administration of justice; (b) barristers must maintain high standards of professional conduct; (c) barristers as specialist advocates in the administration of justice, must act honestly, fairly, skilfully and with competence and diligence; (d) barristers owe duties to the courts, to their clients and to their barrister and solicitor colleagues; (e) barristers should exercise their forensic judgments and give their advice independently and for the proper administration of justice, notwithstanding any contrary desires of their clients; and (f) the provision of advocates for those who need legal representation is better secured if there is a Bar whose members: (i) must accept briefs to appear regardless of their personal beliefs; (ii) must not refuse briefs to appear except on proper professional grounds; and (iii) compete as specialist advocates with each other and with other legal practitioners as widely and as often as practicable. The work of a barrister 15. Barristers’ work consists of: (a) appearing as an advocate; (b) preparing to appear as an advocate; (c) negotiating for a client with an opponent to compromise a case; (d) representing a client in a mediation or arbitration or other method of alternative dispute resolution; (e) giving legal advice; (f) preparing or advising on documents to be used by a client or by others in relation to the client’s case or other affairs; (g) carrying out work properly incidental to the kinds of work referred to in (a)- (f); and (h) such other work as is from time to time commonly carried out by barristers Rule 16 A barrister must be a sole practitioner, and must not: (a) practise in partnership with any person; (b) practise as the employer of any legal practitioner who acts as a legal practitioner in the course of that employment; (c) practise as the employee of any person;4 (d) be a legal practitioner director of an incorporated legal practice; or (e) be a member of a multi-disciplinary partnership. Cab rank principle – Rule 21 A barrister must accept a brief from a solicitor to appear before a court in a field in which the barrister practises or professes to practise if: (a) the brief is within the barrister’s capacity, skill and experience; (b) the barrister would be available to work as a barrister when the brief would require the barrister to appear or to prepare, and the barrister is not already committed to other professional or personal engagements which may, as a real possibility, prevent the barrister from being able to advance a client’s interests to the best of the barrister’s skill and diligence; (c) the fee offered on the brief is acceptable to the barrister; and (d) the barrister is not obliged or permitted to refuse the brief under Rules 95, 97, 98 or 99 NSW Law Society New South Wales Professional Conduct and Practice Rules 2013 (Solicitors’ Rules) http://www.lawsociety.com.au/ForSolictor s/professionalstandards/Ruleslegislation/S olicitorsRules/index.htm Australian Conduct rules – but retaining NSW specific rules Solicitors' Rules - 2 - Purpose and Effect of the Rules 2.1 The purpose of these Rules is to assist solicitors to act ethically and in accordance with the principles of professional conduct established by the common law and these Rules. 2.2 In considering whether a solicitor has engaged in unsatisfactory professional conduct or professional misconduct, the Rules apply in addition to the common law. 2.3 A breach of these Rules is capable of constituting unsatisfactory professional conduct or professional misconduct, and may give rise to disciplinary action by the relevant regulatory authority, but cannot be enforced by a third party Solicitors' Rules - 3 - Paramount duty to the court and and the administration of justice 3.1 A solicitor's duty to the court and the administration of justice is paramount and prevails to the extent of inconsistency with any other duty. 4: Other fundamental ethical duties 4.1 A solicitor must also: 4.1.1 act in the best interests of a client in any matter in which the solicitor represents the client; 4.1.2 be honest and courteous in all dealings in the course of legal practice; 4.1.3 deliver legal services competently, diligently and as promptly as reasonably possible; 4.1.4 avoid any compromise to their integrity and professional independence; and 4.1.5 comply with these Rules and the law. 5: Dishonest and disreputable conduct 5.1 A solicitor must not engage in conduct, in the course of practice or otherwise, which demonstrates that the solicitor is not a fit and proper person to practise law, or which is likely to a material degree to: 5.1.1 be prejudicial to, or diminish the public confidence in, the administration of justice; or 5.1.2 bring the profession into disrepute. 6: Undertakings 6.1 A solicitor who has given an undertaking in the course of legal practice must honour that undertaking and ensure the timely and effective performance of the undertaking, unless released by the recipient or by a court of competent jurisdiction. 6.2 A solicitor must not seek from another solicitor, or that solicitor's employee, associate, or agent, undertakings in respect of a matter, that would require the co-operation of a third party who is not party to the undertaking. Duties of a legal professional Members of the legal profession owe duties: to the law to the courts to their clients to their profession to each other Nature of a professional “An important basic thesis is that as true professionals, we embrace unique ethical responsibilities not because they are prescribed, or because doing so opens a gateway to financial return, or because if discovered in breach we may be disciplined. We embrace them, I certainly trust, because of a basic sense of refined decency and fairness; and albeit on a lesser plane, because we acknowledge them as a reasonable quid pro quo for the substantial privileges admission to this rank accords.” De Jersey CJ; Bar Practice Course final lecture “The ‘fit and proper’ criterion: indefinable but fundamental” 18 th February 2005 De Jersey CJ: “But let there be no doubt. A bad person cannot be a good barrister [or solicitor].* Those “fit” for this role, are imbued with ordinary human decency and fairness, and an acute perception and acceptance of the unique responsibilities which accompany practice…” * words added Two elements to admission: s24: eligibility – which refers to academic qualifications and completion of practical legal training s25: suitability – which refers to whether or not a candidate is a ‘fit and proper person’, and includes (s9) a consideration of whether or not a person is of good fame and character. Legal Profession Uniform Law (NSW) s17 (1)The prerequisites for the issue of a compliance certificate in respect of a person are that he or she- (a) has attained the academic qualifications specified under the Admission Rules for the purposes of this section (the "specified academic qualifications prerequisite" ); and (b) has satisfactorily completed the practical legal training requirements specified in the Admission Rules for the purposes of this section (the "specified practical legal training prerequisite" ); and (c) is a fit and proper person to be admitted to the Australian legal profession. (2) In considering whether a person is a fit and proper person to be admitted to the Australian legal profession(a) the designated local regulatory authority may have regard to any matter relevant to the person’s eligibility or suitability for admission, however the matter comes to its attention; and (b) the designated local regulatory authority must have regard to the matters specified in the Admission Rules for the purposes of this section. Sir Edward Coke: “honesty, knowledge and ability; honesty to execute it truly, without malice, affection, or partiality; knowledge to know what he ought duly to do; and ability, as well in estate as in body, that he may intend and execute his office, when need is, diligently, and not for impotency or probity neglected.” NSW Bar Association v Cummins Spigelman CJ [2001] 52 NSWLR 279 [19] Honesty and integrity are important in many spheres of conduct. However, in some spheres significant public interests are involved in the conduct of particular persons and the state regulates and restricts those who are entitled to engage in those activities and acquire the privileges associated with a particular status. The legal profession has long required the highest standards of integrity. [21]Even in a period where other values have become of significance to the regulation of the legal profession – I refer particularly to the application of competition principles and professional regulation – the traditional professional paradigm still has a vitality of abiding significance. Neither the relationship of trust between a legal practitioner on the one hand, and his or her clients, colleagues and the judiciary on the other hand, nor public confidence in the profession, can be established or maintained, without professional regulation and enforcement. …Clients must feel secure in confiding their secrets and entrusting their most personal affairs to lawyers. Fellow practitioners must be able to depend implicitly on the word and the behaviour of their colleagues. The judiciary must have confidence in those appearing before the courts. The public must have confidence in the legal profession by reason of the central role the profession plays in the administration of justice Clyne v The New South Wales Bar Association “A barrister does not lie to a judge who relies on him for information. He does not deliberately misrepresent the law to an inferior court or to a lay tribunal…he does not, in cross-examination as to credit, ask a witness if he has not been guilty of some evil conduct unless he has reliable information to warrant the suggestion which the question conveys.” Mason P in New South Wales Bar Association v Hamman “I emphatically dispute the proposition that defrauding ‘the Revenue’ for personal gain is of lesser seriousness than defrauding a client, a member of the public or a corporation. The demonstrated unfitness to be trusted in serious matters is identical. …’The Revenue’ may not have a human face, but neither does a corporation. But behind each (in the final analysis) are human faces who are ultimately worse off in consequence of fraud. Dishonest non disclosure of income also increases the burden on taxpayers generally because rates of tax inevitably reflect effective collection levels.” Plagiarism Re Legal Profession Act; re OG, a lawyer [2007] VSC 520 Re Liveri [2006] QCA 152 “it should go without saying that an applicant seeking admission to the legal profession should not have to be warned about the unacceptability of cheating in the course of securing the prerequisite academic qualification.” Re Humzy-Hancock [2007] QSC 34 American Bar Association The continued existence of a free and democratic society depends upon recognition of the concept that justice is based upon the rule of law grounded in respect for the dignity of the individual and the capacity through reason for enlightened self-government. Law so grounded makes justice possible, for only through such law does the dignity of the individual attain respect and protection. Without it, individual rights become subject to unrestrained power, respect for law is destroyed, and rational self-government is impossible. Lawyers, as guardians of the law, play a vital role in the preservation of society. The fulfillment of this role requires an understanding by lawyers of their relationship with and function in our legal system. A consequent obligation of lawyers is to maintain the highest standards of ethical conduct. In fulfilling professional responsibilities, a lawyer necessarily assumes various roles that require the performance of many difficult tasks. Not every situation which a lawyer may encounter can be foreseen, but fundamental ethical principles are always present as guidelines. Within the framework of these principles, a lawyer must, with courage and foresight, be able and ready to shape the body of the law to the everchanging relationships of society. But in the last analysis it is the desire for the respect and confidence of the members of the legal profession and the society which the lawyer serves that should provide to a lawyer the incentive for the highest possible degree of ethical conduct. The possible loss of that respect and confidence is the ultimate sanction. So long as its practitioners are guided by these principles, the law will continue to be a noble profession. This is its greatness and its strength, which permit of no compromise. Judiciary Adversarial system Judge as neutral umpire Parties control issues through pleadings Judge does not decide the truth – but the rights as between the parties Judicial independence Act of Settlement 1701 Security of tenure Appointment Removal Security of income s72 Constitution 72. The Justices of the High Court and of the other courts created by the Parliament-(i.) Shall be appointed by the Governor-General in Council: (ii.) Shall not be removed except by the Governor-General in Council, on an address from both Houses of the Parliament in the same session, praying for such removal on the ground of proved misbehaviour or incapacity: (iii.) Shall receive such remuneration as the Parliament may fix; but the remuneration shall not be diminished during their continuance in office. The appointment of a Justice of the High Court shall be for a term expiring upon his attaining the age of seventy years, and a person shall not be appointed as a Justice of the High Court if he has attained that age… HIGH COURT OF AUSTRALIA ACT 1979 - s 6 Consultation with State Attorneys-General on appointment of Justices Where there is a vacancy in an office of Justice, the Attorney- General shall, before an appointment is made to the vacant office, consult with the Attorneys-General of the States in relation to the appointment. Difficulties with s72: Involvement of political parties in removal process Definition of ‘misbehaviour and incapacity’ Two views Sir George Lush "[T]he word 'misbehaviour' in s 72 is used in its ordinary meaning, and not in the restricted sense of 'misconduct in office'. It is not confined, either, to conduct of a criminal nature…If their [judges'] conduct, even in matters remote from their work, is such that it would be judged by the standards of the time to throw doubt on their own suitability to continue in office, or to undermine their authority as judges or the standing of their courts, it may be appropriate to remove them…[I]t is for Parliament to decide what is misbehaviour, a decision which will fall to be made in the light of contemporary values." Andrew Wells "[T]he word 'misbehaviour' must be held to extend to conduct of the judge in or beyond the execution of his judicial office, that represents so serious a departure from standards of proper behaviour by such a judge that it must be found to have destroyed public confidence that he will continue to do his duty under and pursuant to the Constitution." CONSTITUTION ACT 1902 (NSW)- SECT 53 53 Removal from judicial office (1) No holder of a judicial office can be removed from the office, except as provided by this Part. (2) The holder of a judicial office can be removed from the office by the Governor, on an address from both Houses of Parliament in the same session, seeking removal on the ground of proved misbehaviour or incapacity. (3) Legislation may lay down additional procedures and requirements to be complied with before a judicial officer may be removed from office. (4) This section extends to term appointments to a judicial office, but does not apply to the holder of the office at the expiry of such a term. (5) This section extends to acting appointments to a judicial office, whether made with or without a specific term. JUDICIAL OFFICERS ACT 1986 SECT 41 Removal of judicial officers 41 Removal of judicial officers (1) A judicial officer may not be removed from office in the absence of a report of the Conduct Division to the Governor under this Act that sets out the Division’s opinion that the matters referred to in the report could justify parliamentary consideration of the removal of the judicial officer on the ground of proved misbehaviour or incapacity. (2) The provisions of this section are additional to those of section 53 of the Constitution Act 1902 . The Judicial Commission of NSW assists the courts to achieve consistency in sentencing organises and supervises an appropriate scheme of continuing education and training of judicial officers examines complaints against judicial officers gives advice to the Attorney General on matters concerning judicial officers. Examples of attempts to remove from office Bruce J Vasta J Magistrate Jennifer Betts Brian Maloney http://video.theaustralian.com.au/2020986545/Second-magistrate-fights-forcareer