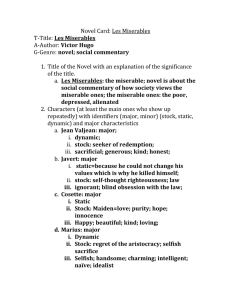

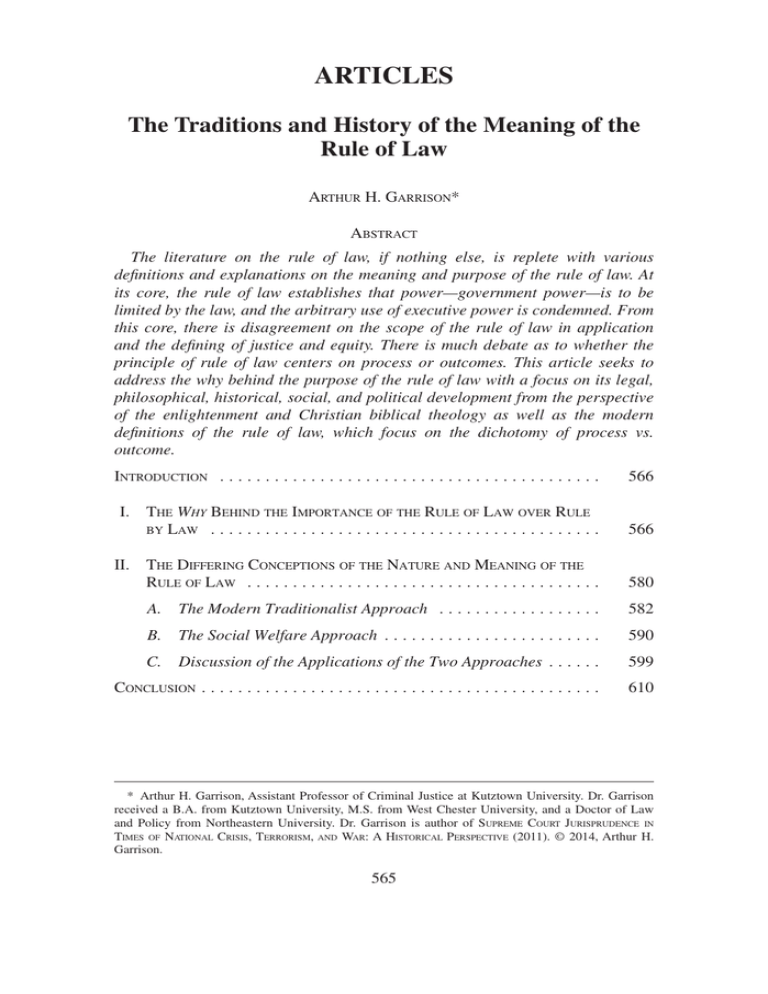

ARTICLES The Traditions and History of the Meaning of the

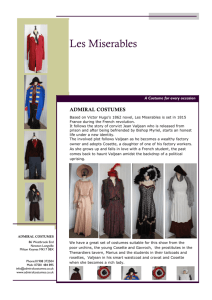

advertisement