Augustus Presentation - Derek Westlund Brown

advertisement

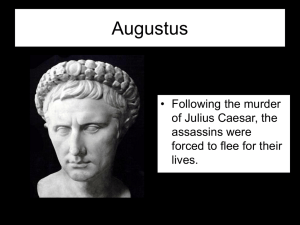

Class Four Caesar Augustus and the Roman Religious Life RECAP 1st Temple 2nd Temple Maccabean Revolt Messianic Hope Goal Today Look at the most influential Caesar in history Caesar Augustus Basic understanding of the religious atmosphere in the Greco-Roman world. In the beginning It goes without saying that Augustus had an incredible influence on Roman society and on history in general. During his reign from 31BC to 14AD, Augustus brought the “Golden Age” of Roman life. What made Augustus so great though? From Child to Emperor Augustus was born in 63 BC as Gaius Octavius, after his father, but would later change his name to Gaius Julius Caesar after Julius Caesar’s death. He was known more commonly as Octavian until in 27 BC he was granted the designation of Augustus Augustus was born to a prosperous family of knights (equites) from Velitrae, a town southeast of Rome. His father, Gaius Octavius, was the first person in his family to become a senator, even rising to the rank of praetor (magistrate ranking below a consul and having chiefly judicial functions) From Child to Emperor However, in 59 BC, Gaius Octavius died and left Octavian’s mother, Atia, a widow. As it would turn out, Atia was the niece of Julius Caesar, and it was Caesar who would be the one to launch the future emperor’s public career At the age of twelve Octavian gave the funeral speech of his grandmother Julia. At only the age of fifteen or sixteen, Octavian was appointed as a priest From Child to Emperor Octavian would also accompany Caesar, who was by then dictator, at his Triumph in 46 BC, and then joined Caesar for a year during his Spanish campaign. Just looking at the young life of Octavian, he already had an incredible amount of opportunities to learn and see how to be a great leader. Octavian was then sent with his friends Marcus Agrippa and Marcus Salvidienus Rufus to Apollonia in Epirus for academic and military studies From Child to Emperor In 44 BC, while Augustus was still studying in Apollonia, he learned that Brutus and Cassius had assassinated Caesar It was during the publication of Caesar’s that Augustus learned he had been posthumously adopted as the Caesar’s son, and designated as his chief heir. Even Caesar saw the potential of young Augustus. Following this, Octavian, who was only eighteen at the time, went against his family’s wishes and set out to claim his inheritance and seek revenge for his adoptive father’s death From Child to Emperor Over the next several months, Octavian consolidated himself as the leader of the friends of the deceased Caesar He also promoted the legacy of Caesar and even hosted the “Games of the Victory of Caesar,” which was a way to promote Caesar’s name and gain the people’s approval. He also found ways to woo Caesar’s military veterans, which ultimately brought tension between himself and Anthony Conflict with Anthony Over the next fourteen years, Octavian and Anthony would struggle with each other to gain supremacy in the state Anthony, Lepidus, and Augustus in 43 BC formed a formal, autocratic Second Triumvirate, where they organized the proscription and execution of many political enemies Finally in 42 BC Augustus and Anthony finally overwhelmed Julius Caesar’s assassins, Brutus and Cassius, who met their deaths Conflict Over the next eleven years the Roman world was divided between Augustus in the west, who had the help of his distinguished admiral Agrippa and the talented diplomat Maecenas, Anthony in the east, who was associated with Cleopatra, the queen of Egypt, and Lepidus who had part of northern Africa During the following years, Augustus would slowly build his reputation and rule by defeating Pompey’s son Sextus Pompeius in Sicily, and fighting campaigns in Illyricum and Dalmatia, as well as forcing Lepidus to retire into private life Rise of Augustus In 31 BC the tension between Anthony and Augustus boiled over, culminating in the naval battle of Actium, where Agrippa, Augustus’ admiral, defeated Anthony. The following year Anthony and Cleopatra committed suicide, which now left Augustus as sole ruler of the Roman Empire. The time of Augustus as the first true Roman emperor was now under way. Augustus as Religious Figure With Augustus as the sole ruler of the Roman Empire, his influence spanned to all the boundaries of the known world What would lead to Augustus being viewed as a religious leader? Religious Figure When looking at Augustus during his reign, it becomes apparent that he was a reformer of the traditional Roman religions. Augustus was able to do what few had done before him; he not only encouraged religion, but also personally helped in the growth of it. Religious Figure The first move towards Augustus as a religious figure started back in in 42BC, during the Second Triumvirate with Lepidus and Anthony, Augustus’ adopted father Julius had been pronounced a god of the Roman state Augustus’ exploitation of this development was seen through the distribution of coins that had himself on one side with the description “Caesar son of God” and then Julius on the other side saying “the God Julius” Religious Figure Once Augustus gained sole rule he found ways to encourage the traditional Roman religions The famous Res Gestae Divi Augusti or “The Achievements of the Divine Augustus” gives evidence to some of the things Octavian did during his reign as emperor This document was one of three documents that was deposited with his will in AD 13 In the Res Gestae, Augustus addresses the Roman people as it was inscribed at Rome Religious Figure For example, in Res Gestae 19 it is written: I built the Senate House, and the Chalcidicum adjacent to it, the temple of Apollo on the Palatine with its porticoes, the temple of the divine Julius, the Lupercal, the portico at the Flaminian circus, which I permitted to bear the name of the portico of Octavius after the man who erected the previous portico on the same site, a pulvinar at the Circus Maximus, (2) the temples on the Capitol of Jupiter Feretrius and Jupiter the Thunderer, the temple of Quirinus, the temples of Minerva and Queen Juno and Jupiter Libertas on the Aventine, the temple of the Lares at the top of the Sacred Way, the temple of the Di Penates in the Velia, the temple of Youth, and the temple of the Great Mother on the Palatine Religious Figure As can be seen, Octavian made sure to invest within the Roman religions. Octavian goes on to say that in 28 BC he “restored eighty-two temples of the gods in the city on the authority of the senate, neglecting none that required restoration at that time.” Later in Res Gestae 21, Octavian demonstrates how far he was willing to go to ensure the encouragement of the tradition religions of the empire. He went so far as to invest gigantic sums of his own money towards the restoration of the temples. Religious Figure Res Gestae says: I built the temple of Mars the Avenger and the Forum Augustum on private ground from the proceeds of booty… From the proceeds of booty I dedicated gifts in the Capitol and in the temples of the divine Julius, of Apollo, of Vesta and of Mars the Avenger; this cost me about 100,000,000 sesterces. 3 In my fifth consulship [28 BC] I remitted 55,000 lb. of aurum coronarium contributed by the municipia and colonies of Italy to my triumphs, and later, whenever I was acclaimed imperator, I refused the aurum coronarium, which the municipia and colonies continued to vote with the same good will as before. Octavian made sure to win the people over by restoring the religious atmosphere to the best it had ever been What do we see? He was a wise ruler who knew how to win the people’s favor He was not afraid to spend huge sums of his own money for the sake of the empire and to meet the needs of the people By doing these things, he gained favor with the people, who saw Octavian as one who brought salvation to them. He was the one who was restoring the cities, not the senate. This made his status grow larger and larger throughout his reign. What do we see? Who else had the ability to spend such large sums? Nobody really. Just to illustrate, the legionary of his day earned 900 sesterces a year, which deductions were made from that sum due to food, arms, and clothing costs. In AD 30-27 Augustus spent around 860 million sesterces buying lands for veterans, then 100 million on the dedication of temples, and then 220 million sesterces on gifts to urban people and to veterans Religious Atmosphere of Rome In order to understand the full impact of what Octavian was doing with his religious reforms, it is important to have an understanding of what the religious atmosphere of Rome was like. Traditional Religious Experience Religion was a staple within the Roman experience The Roman people were very religious, and religion was a part of every aspect of life For example, in the modern world (twenty-first century) religion and politics are separated from one another, but in Roman times they were one in the same. One way of demonstrating this is looking at the position pontifex maximus. The pontifex maximus was the position of high priest in ancient Roman religion. This was a lifetime post and the duties where to administer religious laws and facilitate sacrifices and rituals for the religion Religious Experience This position, which included significant religious duties, was held by Julius Caesar, Augustus and future emperors To have the head political authority, as Augustus did, and be the high priest, demonstrates how intermingled religious and political life were. Interesting enough, priestly positions were not an official profession; rather, these positions were held by a prominent political person, which makes the religious atmosphere of Rome unique from other cultures. Religious Experience Religion was not just intertwined with politics, but everything else. Athletic events were considered religious activities. The Roman calendar was full of religious holidays. Life in Rome was built upon religion and religious activities. Similar to the Bible belt where on every street corner there is a church, in Rome every corner had a temple for the Roman gods. Religious Experience Another aspect to the Roman religious experience is their openness to other gods. Roman religion was a non-exclusive religion. The Romans were known for their worship of many gods and their acknowledgement of even more. There were some gods, like the “state gods,” who received more attention than others. The “state gods,” Jupiter, Juno, and Minerva, were highly worshipped within the city of Rome for they were thought to be the key to the success of Rome. Other gods were important and needed attention as well, which explains why the Roman calendar was full of religious holidays. Religious Experience In the Roman religious experience the relationship between the gods and humans was completely different from a modern view. In their view, the relationship was mutual. If someone needed something, like bread, the person would go to the temple of that particular god that was known to provide food, offer a sacrifice, and then that god would reciprocate by providing for his or her need. Religious Experience This does not mean that everyone’s needs were answered though. It was well known that the gods were fickle and there was no guarantee that they would answer a person’s request, but the Roman concept and practice of honoring the gods demonstrated this idea of having a mutual relationship. This process did not imply that gods not worshipped were less important. The focus however, was on the gods who were believed to be able to affect an outcome for the worshipper. In many ways, this practice mirrored the patronage and benefaction system in place for Roman society. Religious Experience Furthermore, devotees of one god could just as well honor any other gods that they wanted. In Roman culture honor was given at the discretion of the devotee. If they needed something from one particular god, they would go to that god’s temple and honor him. If they needed something from a different god, then they would go over to the other god’s temple. Roman religions were non-exclusive. As has been demonstrated, religion was woven into the fabric of everyday life, and even into the affairs of the state. Religious Practice Knowing that religion was in every part of Roman life, what did their practices and look like? What was the nature of the gods? Roman Practice Roman religion was a religion of doing The Roman religious experience was centered upon sacrifices and rituals. This was the means by which the gods were most honored. Where as in the monotheistic religions belief is a main component, to the Roman religions, belief was good but not of utmost importance for the success of the religion. Religious Practice As Simon Price writes, “’Belief’ as a religious term is profoundly Christian in its implications; it was forged out of the experience which the Apostles and Saint Paul had of the Risen Lord. The emphasis which ‘belief’ gives to spiritual commitment has no necessary place in the analysis of other cultures.” S. R. F. Price, Rituals and Power: The Roman Imperial Cult in Asia Minor (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1984), 11. Religious Practice When understanding an ancient culture’s religion, like that of the Romans, people must realize their own lens they are seeing things through and seek to look at the different culture based purely on its own unique framework. In ancient Rome, belief was good to have, but it was more important to actually practice the religion through sacrifices and rituals. This seems opposite from what Christianity contends that religion is based upon what one believes. Religious Practice Belief was not the only aspect that was not of huge importance in ancient Rome; the necessity for emotion was another one. It was not necessary for devotees to have an emotional attachment to the gods they were honoring. This is another element modern readers need to be mindful of when looking at ancient Roman religions. The notion that emotion is an essential part of any religious life is not necessarily true. Religious Practice As Price comments, “The criterion of feelings and emotions as the test of authenticity in ritual and religion is in fact an appeal to the Christian virtue of religio animi, religion of the soul, that is, the interiorized beliefs and feelings of individuals… That is to apply the standards of one religion to the ritual of another society without consideration of their relevance to indigenous standards.” What Price says is vital to understanding the religious atmosphere of Rome. The “indigenous standard” in ancient Rome was one of doing. Religious Practice This is not to say that belief and emotion were not possible and lacked any sort of value, because it was possible that those elements were a part of the people’s practice, but the point is that it was not essential to the religion. What was essential was that the gods received the proper rituals and sacrifices. Rituals were a way for ancient Rome to conceptualize the world, while sacrifices were a way of displaying religious honor (KEY POINT) Religious Practice The purpose behind this was to mark a distinction between god and man, showing that the one receiving the sacrifice was superior to the one giving it. This was the means by which the Romans were able to relate to the gods. “Certainly some notion of belief is involved. The Romans believed what they were doing was of value; otherwise they would not have done it. However, this was not a unique belief in contrast to other beliefs. It was the worldview of the empire. It simply was the state of affairs “ Fantin, 93. Nature of the gods If rituals and sacrifices were what marked the distinction between god and man, what was the nature of the gods? The nature of the Roman gods was vastly different from the nature of the gods found in modern monotheistic religions Nature of the gods The Roman/Greek gods were more human-like and had limited abilities. They sometimes needed to be persuaded by other gods to act. They could be impulsive. They had limited knowledge. In fact, in some instances some of the gods are hurt in battle. Nature of the gods In the Roman religion, there was a not a god who created the world and the universe, like the God in the monotheistic religions does. Instead, the world and the universe were already in existence when the gods came into power. The reason why people honored the gods through rituals and sacrifices was due to the status gap between themselves and the divine. Nature of the gods These gods were still leaps and bounds ahead of their devotees in status. These gods, although not as mighty seeming as the monotheistic gods, still had the ability to act on behalf of human beings. Even with these gods being temperamental and impulsive like humans, they still were to be honored by the standards of the Roman religion.