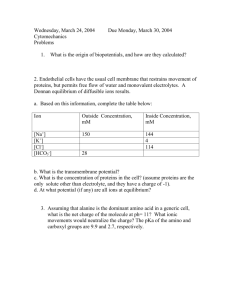

lecture 2

advertisement

2-1 Proteins: structure, translation, etc. Structure of proteins - amino acids, peptide bond, primary-quaternary structures, disulfide bond Protein synthesis -protein translation, co-translational folding, stalling, etc. Protein folding and unfolding - Levinthal paradox, acquisition of native structure, loss of structure 2-2 Amino acid structures methionine (M) isoleucine (I) phenylalanine (F) valine (V) tyrosine (Y) leucine (L) tryptophan (W) aspartic acid (D) glutamic acid (E) aspargine (N) glutamine (Q) serine (S) lysine (K) arginine (R) histidine (H) glycine (G) alanine (A) + + 3 2 threonine (T) cysteine proline 2-3 Amino acid relationships hydrophobic MILV FYW C P Suggested amino acid substitutions Solvent exposed (SEA>30 Å2 , ) Interior (SEA<10 Å2, ) SEA, solvent exposed area small neutral G(A*)ST hydrophilic EDNQ KRH *A is also fairly hydrophobic aromatic Amino acids connected by a line can be substituted with 95% confidence Adapted from D. Bordo and P. Argos (1991) J. Mol. Biol. 217, 721-729. Peptide bond formation 2-4 ©Alberts et al. (1998) You should know the structure of a polypeptide chain (protein)! 2-5 The peptide bond Ri+1 Ri R=side chain O=C-N-H is planar (double-bond character) Phi (Φ) and Psi (ψ) angles can vary; their rotation allows polypeptides to adopt their various structures (alpha-helices, beta-sheets, etc.) cis conformation is rare except for proline potential for steric hindrance 2-6 Protein structure: overview Structural element Description primary structure amino acid sequence of protein secondary structure helices, sheets, turns/loops super-secondary structure association of secondary structures domain self-contained structural unit tertiary structure folded structure of whole protein • includes disulfide bonds quaternary structure assembled complex (oligomer) • homo-oligomeric (1 protein type) • hetero-oligomeric (>1 type) 2-7 Protein structure: helices alpha 3.10 pi - alpha helices are about 10 residues on average - side chains are well staggered, preventing steric hindrance - helices can form bundles, coiled coils, etc. H-bonding amino acids per turn: 3.6 frequency ~97% ~3% 3.0 4.4 rare 2-8 Protein structure: sheets parallel ‘twisted’ anti-parallel - the basic unit of a beta-sheet is called a beta-strand - unlike alpha-helix, sheets can be formed from discontinuous regions of a polypeptide chain - beta-sheets can form various higher-level structures, such as a beta-barrel Green Fluorescent Protein (GFP) 2-9 Protein structure: sheets (detail) - notice the difference in H-bonding pattern between parallel and anti-parallel beta-sheets - also notice orientation of side chains relative to the sheets ‘twisted’ 2-10 Protein structure: turns/loops alpha-helix beta-sheet - there are various types of turns, differing in the number of residues and H-bonding pattern - loops are typically longer; they are often called coils and do not have a ‘regular’, or repeating, structure ribonuclease A loop (usually exposed on surface) 2-11 Ramachandran plot Psi (ψ) no steric clashes Phi (Φ) - Phi (Φ) and Psi (ψ) rotate, allowing the polypeptide to assume its various conformations permitted if atoms are more closely spaced - some conformations of the polypeptide backbone result in steric hindrance and are disallowed - glycine has no side chain and is therefore conformationally highly flexible (it is often found in turns) 2-12 Types of non-covalent interactions interaction nature ionic electrostatic (salt bridge) bond length “bond” strength 1.8-4.0 Å 1-6 (3.0-10 Å kcal/mol for like charges) example positive: K, R, H, N-terminus negative: D, E, C-terminus hydrophobic entropy - 2-3 hydrophobic side chains (M,I,L,V,F,W,Y,A,C,P) H-bond H-bonding 2.6-3.5 2-10 H donor, O acceptor van der Waals attraction/ repulsion 2.8-4.0 <1 closely-spaced atoms; if too close, repulsion aromaticaromatic p-p 4.5-7.0 1-2 F,W,Y (stacked) 2.9-3.6 2.7-4.9 N-H donor to F,W,Y aromaticH-bonding amino group these all contribute to some extent to protein structure & stability; - important to understand extremophilic (or any other) proteins Protein-solvent interactions hydrophilic amino acids (D, E, K, R, H, N, Q) - these amino acids tend to interact extensively with solvent in context of the folded protein; the interaction is mostly ionic and Hbonding - there are instances of hydrophilic residues being buried in the interior of the protein; often, pairs of these residues form salt bridges hydrophobic amino acids (M, I, L, V, F, W, Y, A*, C, P) - these tend to form the ‘core’ of the protein, i.e., are buried within the folded protein; some hydrophobic residues can be entirely (or partially) exposed small neutral amino acids (G, A*, S, T) - less preference for being solvent-exposed or not 2-13 2-14 The disulfide bond protein + protein oxidation protein protein + 2 H+ + 2 e- reduction • disulfide bond formation is a covalent modification; the oxidation reaction can either be intramolecular (within the same protein) or inter-molecular (within different proteins, e.g., antibody light and heavy chains). The reaction is reversible. - most disulfide-bonded proteins are extracellular (e.g. lysozyme contains four disulfide bonds); the conditions inside the cytosol are reducing, meaning that the cysteines are usually in reduced form - cellular enzymes (protein disulfide isomerases) assist many proteins in forming proper disulfide bond(s) 2-15 Protein folding “arguably the single most important process in biology” in the test tube ~40 years versus in the cell ~20 years 2-16 Folding of RNAse A in the test tube denaturation renaturation Incubate protein 100-fold in guanidine dilution of protein hydrochloride into physiological (GuHCl) buffer (aggregation) or urea - the amino acid sequence of a polypeptide is sufficient to specify its three-dimensional conformation Thus: “protein folding is a spontaneous process that does not require the assistance of extraneous factors” Anfinsen, CB (1973) Principles that govern the folding of protein chains. Science 181, 223-230. 2-17 Levinthal paradox in vitro in vivo denatured protein: random coil 106 possible conformations folding folding Native protein 1 stable conformation t = seconds or much less t = seconds 2-18 Protein folding theory • limited number of secondary structure elements: helices, sheets and turns • folding can be thought to occur along “energy surfaces or landscapes” Dobson, CM (2001) Phil Trans R Soc Lond 356, 133-145 2-19 Folding of lysozyme hydrophobic collapse - upon dilution of unfolded protein in buffer, the protein will ‘collapse’ onto itself, trying to bury as many hydrophobic surfaces as possible - in doing so, the protein may fold properly, or: - misfold and aggregate - go through a ‘trapped intermediate’ stage • hen lysozyme has 129 residues, consists of 2 domains (α and β) Protein synthesis: the ribosome 2-20 Yusupov et al. (2001) Science 292, 883. - whole 70S ribosome from Thermus thermophilus at 5.5Å - small (30S) subunit: 16S RNA, ~20 proteins - large (50S) subunit: 23S RNA, 5S RNA, >30 proteins - high concentration in the cell (~ 50 μM) Protein synthesis cycle 2-21 interface view of 50S subunit E-, P-, A-site tRNAs and mRNA 1. acylation of tRNAs with respective amino acids 2. binding of tRNA charged with methionine to P-site on the AUG start codon (present on the mRNA) 3. next tRNA charged with appropriate amino acid binds A-site 4. transpeptidation (peptide bond formation) between P-site (N-terminal) amino acid and A-site amino acid leads to the growth of the polypeptide chain. The catalysis is by the peptidyltransferase, which consists only of RNA. The ribosome is thus a ribozyme. 5. the E-site represents the ‘exit’ site for the uncharged tRNA 6. release from tRNA and disassembly then occurs 2-22 Elongation of the polypeptide chain - PT = peptidyltransferase site - rRNAs are in grey - proteins are in green - polypeptide chain model is shown to traverse the ribosome channel from the PT site to the polypeptide exit site adapted from Selmer et al. (1999) Science 286: 2349-2352 - the channel/tunnel and exit site are quite narrow, meaning that there is likely to be little if any co-translational protein folding in the channel - possibility of an alpha-helix forming? (“yes”) 2-23 Co-translational protein folding Fact: - first ~30 amino acids of the polypeptide chain present within the ribosome is constrained (the N-terminus emerges first) folding assembly Assumption: as soon as the nascent chain is extruded, it will start to fold co-translationally (i.e., acquire secondary structures, super-secondary structures, domains) until the complete polypeptide is produced and extruded Observing co-translational folding Experiment: 1. translate firefly luciferase RNA in vitro in the presence of 35S-methionine for 2 min 2. Prevent re-initiation of translation with aurintricarboxylic acid (ATCA): ‘synchronizing’ 3. at set timepoints, quench translation, incubate with proteinase K (digests unstructured/non-compact regions in proteins, but not folded domains/proteins) 4. add denaturing (SDS) buffer, then perform SDSPAGE (polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis) 5. dry gel, observe by autoradiography Firefly Luciferase (62 kDa) Result: 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 10 12 min 60 kDa 40 kDa 20 kDa no ProK N-terminal domain (~22 kDa) 2-24 C-terminal domain (~40 kDa) 2 with ProK 3 4 5 6 7 8 10 12 min 60 kDa 40 kDa 20 kDa 2-25 Antibiotics & protein synthesis antibiotics can be useful tools for manipulating translation, folding antibiotic effect cyclohexamide inhibits the eukaryotic peptidyltransferase; prevents release of the polypeptide chain. Can be used to isolate ribosome-nascent chain complexes chloramphenicol inhibits the prokaryotic peptidyltransferase puromycin causes premature chain termination and release from ribosome. Puromycin is similar to a tyrosyl-tRNA and acts as a substrate during elongation. Once added to the carboxyl end of the nascent chain, protein synthesis is aborted tetracycline inhibits aminoacyl tRNA binding to the A-site kanamycin causes misreading of the mRNA streptomycin causes misreading of the mRNA ssrA RNA in bacteria 2-26 Problem: - turnover (degradation) of mRNA occurs very quickly in bacteria, and the 3’ end of the mRNA has a higher probability of being degraded first - if the stop codon is removed, there are no signals for mRNA release from the ribosome, and the mRNA will stall Solution: - SsrA, or 10SA RNA is a small RNA (363 nt) that resembles a tRNA and can be charged with alanine. It is placed into the peptidyltransferase site by the protein SsrB - SsrA can be used as a template, and codes a peptide, ANDENYALAA - the fusion protein containing this sequence is recognized and degraded by the ClpAP or ClpPX proteases 2-27 Nascent chain stalling in eukaryotes - can make proteins that are of a defined length by translating an RNA that is truncated at the 3’ end (i.e., has no stop codon) Steps: 1. linearize a vector encoding a gene of interest using a restriction enzyme, such that the cut is precisely where you want the polypeptide to end (before the stop codon) 2. make RNA using nucleotides and polymerase enzyme 3. add to an in vitro translation system (rabbit reticulocyte lysate), which has all of the required components to translate the RNA 4. if the RNA is not truncated, the full-length protein will be made and released; if the RNA is truncated, it will remain bound to the ribosome Note: the protein can be labeled this way with co-translational folding still takes place 35S-methionine; 2-28 Chain stalling: in practice Fact: only full-length firefly luciferase is functional Goal: show that firefly luciferase can adopt a folded, functional conformation co-translationally Experiment: 1. prepare DNA construct that encodes firefly luciferase and an extra 35 amino acids at its C-terminus 2. digest construct such that the last 2 amino acids and the stop codon are removed 3. prepare RNA using polymerase and nucleotides 4. in vitro translate the RNA in rabbit reticulocyte lysate 5. assay for firefly luciferase activity (light emission at 560 nm occurs when luciferin substrate is oxidatively decarboxylated) Problem? Hint: does this experiment show physiological relevance? Protein folding: in 3 different environments 2-29 • ex vivo refolding rabbit reticulocyte lysate - rabbit reticulocyte lysate is an abundant source of molecular chaperones, many of which are ATP-dependent • in vitro folding environments - protein folding (from denaturant), when possible, requires the proper environment: proper pH, salts, concentration of protein, temperature, stabilizing agents (e.g., other proteins, glycerol, etc.) • in vivo folding - molecular chaperones, protein folding catalysts, proper redox environment, availability of binding partners 2-30 Following the acquisition of (native) structure denaturation • regain of 2º, 3º and 4º structures - by circular dichroism and fluorescence measurements - by other criteria (e.g., native gel electrophoresis, SEC, protease sensitivity assays, etc.) • regain of activity - activity not necessarily enzymatic renaturation native structure? refolding unfolding Circular dichroism Acquisition of native structure: examples • actin - chemically denatured actin can be refolded by incubating it in rabbit reticulocyte lysate; native gel electrophoresis, and binding to DNAse I is used to assess folding • various small proteins (RNAse A, lysozyme, etc.) - can be denatured chemically and refolded simply by dilution of the denaturing agent; activity assays are available, but folding can be monitored using spectroscopic techniques • other - small-angle light x-ray scattering (SAXS), NMR are some other techniques used to monitor protein folding 2-31 2-32 Protein denaturants • high temperatures - cause protein unfolding, aggregation • low temperatures - some proteins are sensitive to cold denaturation • heavy metals (e.g., lead, cadmium, etc.) - highly toxic; efficiently induce the ‘stress response’ • proteotoxic agents (e.g., alcohols, cross-linking agents, etc.) • oxygen radicals, ionizing radiation - cause permanent protein damage • chaotropes (urea, guanidine hydrochloride, etc.) - highly potent at denaturing proteins; often used in protein folding studies 2-33 Following the loss of structure • loss of secondary structure - the far-UV circular dichroism spectrum of a protein changes at the so-called ‘melting temperature’ or Tm - fluorescence characteristics will likely also change • loss of tertiary structure - the far- and near-UV circular dichroism spectra of a protein change, but the Tm of both spectra may be different - fluorescence characteristics will likely also change • loss of activity - the activity of a protein can be monitored over time • aggregation - can measure light scattering (e.g., at 320 nm) spectrophotometrically, or by detecting the protein in a precipitate Loss of structure: example intermediate Urea (M) 0 0 1 2 chymotrypsin no Yes Yes Yes folded unfolded Far-UV spectrum native unfolded Fluorescence spectrum 2M urea Bacterial luciferase (α subunit) Noland et al. (1999) Biochemistry 38, 16136. 2-34