Researching & reforming European private law - China

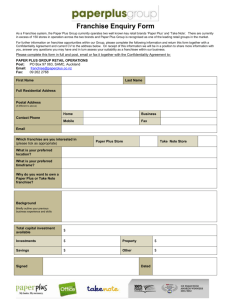

advertisement

HARMONIZATION OF EUROPEAN PRIVATE AND COMMERCIAL LAW CESL Academic Conference (Beijing, 2011) Prof. Tibor Tajti © THE STARTING POSITION: THE “LEGAL MAP” OF EUROPE Herein of the European Legal Families, SubGroups and the Differences Wikipedia’s Classification Scandinavian law 1 Scotland: mixed Russian law (?) Common law FrancoLatin law Mixed: Franco/Latin & Germanic Germanic law THE AVENUES OF RAPPROCHEMENT OF EUROPEAN PRIVATE AND COMMERCIAL LAWS “For the transnational lawyer indeed, the present European situation is as that of a traveler compelled to use a number of different local maps each one of difficult use to foreign lawyers and sometimes containing information which (due to bias or hidden assumptions of municipal lawyers) can be misleading. […].” Mauro Bussani & Ugo Mattei (eds.), The Common Core of European Private Law (Kluwer Law International, 2002), Preface: the Context, at 1-2. The Avenues of Rapprochement Research Groups 1. Lando Commission 2. The Acquis Group 3. The Common Core Group (etc.) EU Legislation -Directive on time share agreements (etc.) REFORM PROJECTS EBRD – secured transactions law reform GTZ – Serbia (mortgage law and land registries) ORGANIC DEVELOPMENT - Popular contracts (e.g., franchise, leasing) - Regulatory competition (e.g., 2002 amendment of the French Commercial Code) [Impact of] INTERNATIONAL EFFORTS 1.The Unidroit Principles of Int’l Commercial Contracts (2010: 3rd edition) 2.CISG (Uncitral) EU LEGISLATION A FRAGMENTED APPROACH “After a long period of specific consumer directives (19842001), a new phase was inaugurated in 2001, which has been defined by the redrafting and systematization of consumer regulations in the quest for an internal market with a more organic and coherent common law. This phase is characterised by interaction between consumer regulations and the creation of a new European Contract Law …” Micklitz, Stuyck, Terryn and Droshout, Consumer Law (Hart, 2010, at 165. UNDER THE AUSPICES OF THE ROME TREATY CONSUMER PROTECTION • Doorstep sales (85/577) • Consumer Credit Directive • • • • (85/102) Directive on unfair terms in consumer contracts (93/13) Timeshare Directive (94/47) Distance Selling Directive (97/7) Price Indication Directive (98/6) (etc.) OTHER • Primarily of administrative nature restricting freedom of contract: - Directive 86/653 on the coordination of the law of the Member States relating to the self-employed agent • Conflicts of law - Regulation 44/2001 on Jurisdiction and the Recognition of Judgments in Civil and Commercial Matters (Brussels I) IS THERE A FUTURE FOR THE EUROPEAN CIVIL CODE? MAURO BUSSANI: “The defense of the status quo [that the time … is not ripe to enact whatever Restatement or Civil Code] … fits perfectly with the need of the professional elite to keep the leadership over national and transnational legal affairs … ” Mauro Bussani, the Driving Forces behind a European Civil Code, Zbornik Prav. Fak. Sveuč. Rij. Suppl. Br. 3, xx-xx, at 11. Reality v. Wishes REALITY “whilst it seems that the European contract law initiative as described in the Commission communication of 11 October 2004 (COM(2004)0651) and reported on in the Commission's First Annual Progress Report (COM(2005)0456) should be seen primarily as an exercise in better lawmaking at EU level, it is by no means clear what it will lead to in terms of practical outcomes or on what legal basis any binding instrument or instruments will be adopted […]” WHAT WOULD BE NEEDED The European Parliament “… reiterates its conviction, expressed in its resolutions of 26 May 1989, 6 May 1994, 15 November 2001 that a uniform internal market cannot be fully functional without further steps towards the harmonisation of civil law […].” and 2 September 2003, WHERE TO GO FROM HERE? The Common Frame of Reference “That is a text serving as a source of inspiration for law making and law teaching at all levels.” Christian von Bar, A Common Frame of Reference for European Private Law - Academic Efforts and Political Realities, Electronic Journal of Comparative Law, at 1 (< www.ejcl.org/121/art121-27.pdf >). The Seven Possible Avenues of Development GREEN PAPER FROM THE COMMISSION on policy options for progress towards a European Contract Law for consumers and businesses (Brussels, 1.7.2010, COM(2010)348 final) Option 1: “mere” publication of the DCFR (for legislators, teachers and private parties) Option 2: an “official toolbox for legislator” Option 3: EU Commission recommendation to Member States to incorporate the DCFR into national laws Option 4: DCFR as an alternative system to national laws that could be chosen by parties (“optional instrument”) Option 5: EU Directive with minimum common standards Option 6: EU Regulation with uniform rules replacing national laws Option 7: European Civil Code HOW IS THE DCFR RESOLVING TENSIONS? The Case of the doctrine of culpa in contrahendo (“fault in contracting”) Black’s Law Dictionary: “The principle that parties must act in good faith during preliminary contract negotiations.” The Difference GERMAN LAW “… contracting parties are under a duty, classified as contractual, to deal in good faith with each other during the negotiation stage, or else face liability, customarily to the extent of the wronged party’s reliance.” ENGLISH & US LAW a/ Generally accepted view: common law does not have a counterpart b/ Kessler & Fine: “… the doctrines of negligence, estoppel, and implied contract, among others, have … served many of the doctrinal functions of culpa in contrahendo.” The Common Frame of Reference on Culpa in Contrahendo Negotiation and confidentiality duties II. – 3:301: Negotiations contrary to good faith and fair dealing (1) A person is free to negotiate and is not liable for failure to reach an agreement. (2) A person who is engaged in negotiations has a duty to negotiate in accordance with good faith and fair dealing and not to break off negotiations contrary to good faith and fair dealing. This duty may not be excluded or limited by contract. (3) A person who is in breach of the duty is liable for any loss caused to the other party by the breach. (4) It is contrary to good faith and fair dealing, in particular, for a person to enter into or continue negotiations with no real intention of reaching an agreement with the other party. RESEARCH GROUPS ON EUROPEAN PRIVATE LAW ‘In matters of private law, current attempts to produce a European private code or at least to establish common principles of law are … basically in ‘German’ hands (though one must also mention the ‘Trento Project’ run mainly from Italy.’ […].’ Basil Markesinis (with Jörg Fedtke), Engaging with Foreign Law (Hart Publishing, 2009), p. 164. Research Groups on European [Pure] Private Law • Commission on European Contract Law (Lando Commission) [< http://www.jus.uio.no/lm/eu.principles.lando.commission/doc.html >] • Study Group on a European Civil Code [ < http://www.sgecc.net/ > ] • The Acquis Group – European Research Group on Existing EC Private Law [ < http://www.acquis-group.org/ > ] • The Common Core of European Private Law Project (Trento Group) [< http://www.jus.unitn.it/dsg/common-core/meeting_10_project.html > ] • Commission on European Family Law (CEFL) [ < http://www.ceflonline.net/ >] • European Centre of Tort and Insurance Law (ECTIL) [< http://www.ectil.org/ >] • European Group on Tort Law (Tilburg Group) [< http://civil.udg.es/tort/ >] • Ius Commune Casebooks for the Common Law of Europe [< http://www.casebooks.eu >] • SECOLA (Society of European Contract Law) [ < http://www.secola.org/ > ] • Joint Network on European Private Law (CoPECL) [< http://www.copecl.org/ >] • Uniform Terminology for European Private Law [< http://www.uniformterminology.unito.it/ >] Law Reviews: • European Private Law Review [< http://www.kluwerlawonline.com/productinfo.php?pubcode=ERPL> ] • Zeitschrift für Europäisches Privatrecht [ http://rsw.beck.de/cms/main?site=ZEuP> ] Unorthodox yet Critical Questions • Is it still justified to separate private and commercial law in the 21 st century? • Why the neglect of the problems and laws of other parts of Europe [but the few main systems]? • Why the resistance & ignorance to influences coming outside Europe (primarily United States) in the field of private and commercial law – and not in many regulatory fields (e.g., antitrust/competition law, capital markets and securities regulation)? • Where are the concrete results of the many EU & European Projects? Why the constant rewriting? • Is the European solution rather in minimal harmonization of private law and enactment of common ‘regulations’ to address concrete problems? (E.g., tailor-made consumer protection law). Nothing Changed since 2003? MAURO BUSSANI in 2003 “There is a strong disagreement among the experts … [s]ome of them maintain that a code is absolutely necessary in order to shape a truly common European law, while other believe that this project is unworkable, either because the divergences among the national systems are still too serious (and this implies that the situation may change in the future, and a code may eventually be feasible), or because legal harmony can, or must, be achieved by means other than a code.” Mauro Bussani, the Driving Forces behind a European Civil Code, in: Zbornik Pravnog Fakulteta Sveučilišta u Rijeci, [the law review of the Law School of Rijeka, Croatia], Suppl. Broj 3, xx-xx (2003), at 9. THE COMMISSION ON EUROPEAN CONTRACT LAW (THE LANDO COMMISSION) “The Commission on European contract law is the author of the Restatement called Principles of European Contract Law in the framework of the Resolutions of the European Parliament on the Codification of Private Law” < http://www.jus.uio.no/lm/eu.principles.lando.commission/doc.html#9 > The Aim of the Principles The PECL’s primary objective is “to serve as a basis for a European Code of Contracts. They are intended as a first step [and yet] they differ from the American Restatement on Contracts because they require a more radical approach. They do not simply select from among several solutions extant in a single legal system; as they must provide workable solutions for a widely divergent legal environment, they are designed to embody rules that do not exist as such in any European legal system.” Ole Lando, Principles of European Contract Law: An Alternative to or a Precursor of European Legislation, 40 Am. J. Comp. L. 573, 577 (1992) (published also in RabelsZ 261 [1992]). Achievements 1982: establishment of the commission -non-governmental body of legal scholars (mostly academics) -none appointed by a government -subsidies from the EU and various foundations and enterprises 1995: published the first part of the Principles (PECL) (with comments and notes) 1998: published the second edition of the Principles (PECL) [< http://www.jus.uio.no/lm/eu.contract.principles.1998/index.html>] 2003: part III of the PECL However: the PECL remains soft law THE ACQUIS GROUP The ‘Principles of Existing EC Contract Law’ (Acquis Principles) [English text available at <http://www.acquis-group.org/>] The Acquis Group’s Mission Statement THE REASON: “On 12 February 2003, the European Commission published its communication ‘A More Coherent European Contract Law - An Action Plan.’ In order to foster a transparent consultation procedure, the Commission has asked stakeholders to comment on the issues raised. One of the most important fields of discussion concerns the intention of the Commission to form a ‘Common Frame of Reference.’ THE MISSION: “The Acquis Group intends to contribute to the task of providing material for the Commission to build the Common Frame of Reference. Its task is to derive common "Principles of the Existing EC Private Law" following a new approach by focusing upon the genuine EC Law itself instead of comparing different national legal orders. Its research, which will be published as "Principles of the Existing EC Contract Law", can serve as building material for the Common Frame of Reference.” See <http://www.acquis-group.org/> THE TRENTO PROJECT “Stating it in very simple terms, we are seeking to unearth the common core of the bulk of European private law, i.e., of what is already common, if anything, among the different legal systems of European Union member states.” Mauro Bussani & Ugo Mattei, the Common Core Approach Goals – Legal Cartography < http://www.jus.unitn.it/dsg/common-core/approach.html > The ‘Combined’ Method HOW? - Schlesinger’s Factual Approach • Hypotheticals (series of facts constituting hypothetical cases) used to allow for dialogue among legal scholars with different cultural background. • Questionnaires; Rudolf b. Schlesinger & P. Bonassies (gen. eds.), Formation of Contracts: A Study of the Common Core of Legal Systems (Dobbs Ferry, N.Y., Oceana, London, 1968. WHAT? - Sacco’s Analysis of Legal Formants • Presumption that statutory (written) law, scholarly analysis & court decisions do not provide a full picture of what makes law • Domestic lawyers presume many ‘legal & meta-legal formants’ which are invisible to foreigners • E.g., the same rule in the Civil Codes of two countries may produce radically different outcomes Rodolfo Sacco, Legal Formants (1991), American Journal of Comparative Law. The Questionnaires: THE MORTGAGE GROUP FIRST PART - General questions: Please provide an overview of the basic features of the law in your country as it relates to security rights over immovable assets. Your overview should contain an outline of the following features of your system: i) The range of immovable assets which may be subjected to security rights; ii) The range of types of security which may be held over immovable assets; iii) The range of methods by which security rights are created and the role of registration; iv) The extent to which the major form of security right is accessory to the loan it secures (nature and degree of accessority) and the extent to which the major form of security right is specific to the immovable assets over which it is held (nature and degree of specificity); […]. The Questionnaires: THE MORTGAGE GROUP SECOND PART – Hypothetical cases: E.g., “Case 15 Daniel granted bank B a security over his house for a loan. Five years later Daniel defaults on the loan. The bank wants to enforce its security by availing itself of a clause of the security agreement whereby, if Daniel defaults, bank B automatically becomes absolute owner of the house. Daniel claims that such a clause is invalid and unenforceable.” [US: strict foreclosure – Civilian systems: lex commissoria] The Questionnaires: THE MORTGAGE GROUP THIRD PART – Meta-Legal Formants: “[…] Finally, the level called “Metalegal Formants” asks the reporter to provide any other information that she considers relevant and that affect the operative and descriptive levels, such as - policy considerations, - economic factors, - social context and values, - reform proposals, - as well as the structure of the legal process (organization of courts, administrative structure and practice, etc.) when it is relevant for the solution of a given problem.” Common Core Publications • Published Books Reinhard Zimmermann and Simon Whittaker, Good Faith in European • • • • • • • • • • • Contract Law, Cambridge University Press, 2000 (ISBN 0-521-77190-0) James Gordley, The Enforceability of Promises in European Contract Law, Cambridge University Press, 2001 (ISBN 0-521-79021-2) Mauro Bussani and Vernon V. Palmer, Pure Economic Loss in Europe, Cambridge University Press, 2003 (ISBN 0-521-82464-8) Eva-Maria Kieninger, Security Rights in Movable. Property in European Private Law, Cambridge University Press, 2004 (ISBN 0-521-83967-X) and 2009 (ISBN-13: 9780521104142) Franz Werro and Vernon V. Palmer, The Boundaries of Strict Liability in European Tort Law, “, Stämpfli-Carolina Academic Press, 2004 (ISBN 1-59460-005-8 / 978-1-59460-004-3) Ruth Sefton-Green, Mistake, Fraud and Duties to Inform in European Contract Law, “Cambridge University Press, 2005 (ISBN 0-521-84423-1) and 2009 (ISBN-13: 9780521844239) Michele Graziadei, Ugo Mattei, Lionel Smith, Commercial Trusts in European Private Law, Cambridge University Press, 2005 (ISBN 0-521-84919-5) and 2009 (ISBN-13: 9780521849197) Barbara Pozzo, Property and Environment -.Old and New Remedies to Protect Natural Resources in the European Context, Stämpfli-Carolina Academic Press, 2007 (ISBN 978-3-72722030-2) Thomas MÖllers and Andreas Heinemann, The Enforcement of Competition Law in Europe “Cambridge University Press, 2008 (ISBN-13: 9780521881104) Monika Hinteregger , Environmental Liability and Ecological Damage in European Law, “Cambridge University Press, 2008 (ISBN-13: 9780521889971) J. Cartwright and M. Hesselink, Precontractual Liability in European Private Law, Cambridge University Press, 2009 (ISBN-13: 9780521516013) G. Brüggemeier, A. Colombi Ciacchi and P. O’Callaghan (eds), Personality Rights in European Tort Law, Cambridge University Press, 2010 (ISBN-13: 9780511685989). THE EBRD SECURED TRANSACTIONS REFORM PROJECT “Recognising the potential role of security in easing the chronic shortage of credit in the former communist countries, the EBRD selected secured transactions laws for its first major legal transition project in 1992. Since then, it has been constantly working to achieve improvement in this area.” John Simpson & Joachim Menze, Ten Years of Secured Transactions Reforms (Law in Transition, 2000), at 20. The EBRD Model Law 1994: Final Draft of the EBRD Model Law on Secured Transactions (accepted on the Annual Meeting in St. Petersburg/Russia) - compatible with UCC Article 9 as well as with the Australian, Canadian and New Zealand’s Personal Property Security Acts - tried to find the balance between the registration-based common law systems and the registration-hostile German law (yet more influenced by common law solutions) Later: - Core Principles for a Secured Transactions Law (< http://www.ebrd.com/pages/sector/legal/secured/core.shtml >) - Guiding principles for the development of a charges registry ORGANIC DEVELOPMENT ILLUSTRATED THE FATE OF NEWCOMER ADVANCED CONTRACTS IN CENTRAL AND EASTERN EUROPE: FRANCHISE CONTRACTS How Do Courts Shape Development in CEE? • 1 Beginning of transition to capitalism 1990 New transaction appears Supreme (or high) Court decision - Voluntary adherence - 1995 1998 First disputes & problems - Court proceedings 2003 2009? If the local parliament not “too busy” with other things – will become regulated FRANCHISE IN HUNGARY (1) • More than 500 businesses claim to be a ‘franchise system’ on the Hungarian Franchise Associations’ website; • Irrespective of the importance, ‘franchise’ is not a ‘nominated’ (i.e., regulated) contract in Hungary; - plan: to include it into the new Civil Code (IN THE MEANTIME BECAME EGULATED BY THE CIVIL CODE, BECAME A NOMINATED CONTRACT) - [earlier] in case of dispute, the courts could choose to apply the rules on one of the following nominated contracts: 1. ‘sales’ (“adásvétel”) or 2. ‘commission’ (“megbízási szerződés”) or 3. undertaking contract (“vállalkozási szerződés”) or 4. licensing. • PRICE: UNCERTAINTY AS TO THE RIGHTS AND DUTIES OF PARTIES Nagy Csongor István & Zsófia Oláh, Chapter on Hungary, volume I, p. 289, in: Messmann & Tajti, the Case Law of Central and Eastern Europe – Enforcement of Contracts (EUP, 2010). FRANCHISE IN HUNGARY (2) The problem of CHARACTERIZATION: - In case of ‘franchise’ agreements, the court has to apply the rules of that nominated contract, which DOMINATES in the given contract (LEVEL OF SUBJECTIVITY?); - E.g., the obligations of the FRANCHISEE: a/ If rules on commission contracts are applied: - due diligence but NOT achieving a particular result b/ If rules on undertaking contracts are applied: - due diligence INSUFFICIENT – particular result must be achieved (e.g., establishing a clientele of a certain level) FRANCHISE IN POLAND: CAN THE ASYMMETRIC NATURE OF FRANCHISE BE TOLERATED? Decision of the Appeal Court in Katowice (4 March 1998, 1 ACa 636/98) - Franchisees wanted to get out of franchise as the scheme has proved to be unprofitable to them; - Have tried to rely on the argument that the franchise contract was asymmetric and their business failed because franchisor dictated everything; - Argument: the franchise contract cannot be enforced as its asymmetric nature is against the principles of the freedom of contract and good morals; - First instance courts ruled for the plaintiffs (franchisee) – yet the Appeal Court ruled against the application of “inherited old concepts of morals”; FRANCHISE IN POLAND Excerpts from the Judgment (2) A. Nature of the newcomer ‘franchise’: “There cannot be any doubt that [franchise] is an innominate contract, typified by mixed content, merging elements of such nominated contracts as lease of rights, sale, mandate, license and agency.” B. The asymmetric nature: “Distributive franchise is usually featured by strong dependence, even subordination, to the person organizing the distribution network. Charging uniform prices for given types of products is also a feature this way of doing business. Granting the network partners a free hand to decide on prices could constitute a hold on development of the distributive network. […]. There are no grounds to share the plaintiff’s view that only they were burdened with the commercial risks of the business undertaking. It is the franchisor who shares with their partners its schemes of conducting business activity, allows the use of its business name, trademark, logotypes, professional experience etc. Failures in the pursuit of such activity cannot remain without any impact on the general image of the franchisor on the market, its commercial standing, competitiveness …” (Messmann & Tajti, p. 656-57.) .” FRANCHISE IN POLAND Excerpts from the Judgment (3) C. Can the franchisor charge royalties in addition to fees (or charging two ‘fees’)? “The Circuit Court did not pay sufficient attention to the scope of the respective obligations of the franchisor and to the nature of the contract concluded by the parties. [Yet to do so would have been important given that by the virtue of this contract] the franchisor granted to its partners not just access to a complex network but also to its intellectual property rights, [and on top of that it obliged itself to] provide on-going help [to franchisees] in realization of the commercial undertaking. There are, therefore, no grounds to conclude, as the Circuit Court did, that the two types of fees overlap and that the provision regarding the obligation to pay the initial fees violates good morals.” Messmann & Tajti, at 659. Thank you for your attention and questions!